Maerl (Lithothamnion corallioides)

Distribution data supplied by the Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS). To interrogate UK data visit the NBN Atlas.Map Help

| Researched by | Frances Perry & Angus Jackson & Dr Samantha Garrard | Refereed by | Dr Christine Maggs |

| Authority | (P.L.Crouan & H.M.Crouan) P.L.Crouan & H.M.Crouan, 1867 | ||

| Other common names | - | Synonyms | - |

Summary

Description

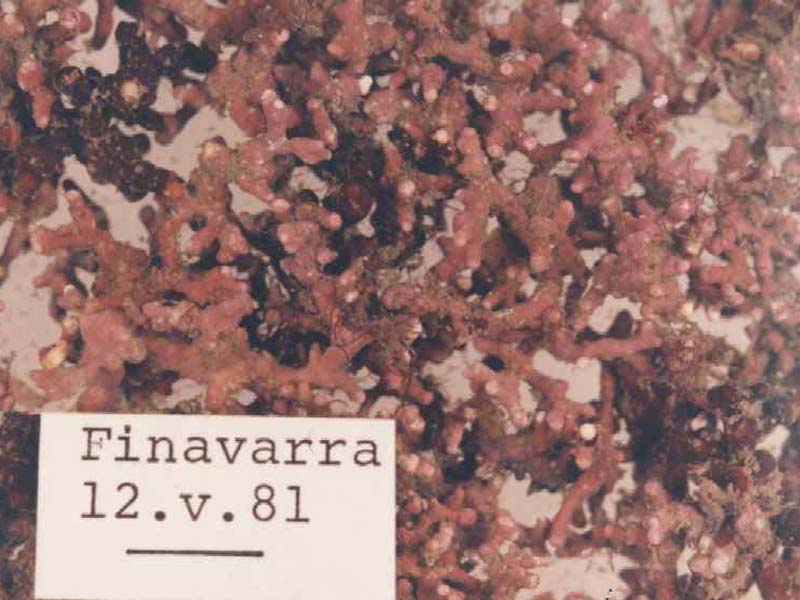

An unattached, fragile, alga with a calcareous skeleton. It is very similar to and often confused with Phymatolithon calcareum. Its form is very variable but it commonly occurs as highly branched nodules forming a three-dimensional lattice. Individual plants may reach 4 - 5 cm across and are bright pink in colour when alive but white when dead.

Recorded distribution in Britain and Ireland

Patchily distributed along the exposed western coasts of the southern British Isles. Locations include the west and south-west of Ireland, the south-west corner of Wales and a few sites off the south coast of England.

Global distribution

West and south-west British Isles south to the Canary Isles (unconfirmed records from Mauritania and Cape Verde). Also found in the Mediterranean.

Habitat

Typically found at less than 20 m depth on sand, mud or gravel substrata in areas that are protected from strong wave action but have moderate to high water flow. Usually found as unattached plants forming beds of coralline algal gravel (maerl) in the sublittoral and occasionally lower littoral. The crustose form is very rare in the British Isles. Typically found together with Phymatolithon calcareum.

Depth range

1-30Identifying features

- Unattached, un-jointed coralline algae.

- Bright pink in colour when live, grey white when dead.

- Often complex lattice with branches typically less than 1 mm in diameter.

- Very brittle.

- Branches covered in low mounds.

- Surface slightly glossy.

Additional information

Maerl is a generic name for certain coralline algae that grow unattached on the sea bed. Only two instances of the crustose form of Lithothamnion corallioides have been recorded from the British Isles; in Dorset and Devon.

Listed by

Biology review

Taxonomy

| Level | Scientific name | Common name |

|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Rhodophyta | Red seaweeds |

| Class | Florideophyceae | |

| Order | Hapalidiales | |

| Family | Hapalidiaceae | |

| Genus | Lithothamnion | |

| Authority | (P.L.Crouan & H.M.Crouan) P.L.Crouan & H.M.Crouan, 1867 | |

| Recent Synonyms | ||

Biology

| Parameter | Data | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical abundance | High density | ||

| Male size range | |||

| Male size at maturity | |||

| Female size range | 3-10 cm | ||

| Female size at maturity | |||

| Growth form | Algal gravel | ||

| Growth rate | 1-2 mm/year | ||

| Body flexibility | None (less than 10 degrees) | ||

| Mobility | Sessile, permanent attachment | ||

| Characteristic feeding method | Autotroph | ||

| Diet/food source | Autotroph | ||

| Typically feeds on | Not relevant | ||

| Sociability | Not relevant | ||

| Environmental position | Epilithic | ||

| Dependency | No information found. | ||

| Supports | Independent | ||

| Is the species harmful? | No | ||

Biology information

Lithothamnion coralloides forms dense but relatively open beds of algal gravel. Beds of maerl form in coarse clean sediments of gravels and clean sands, and occur either on the open coast or in tide-swept channels of marine inlets (the latter are often stony). In fully marine conditions, Lithothamnion coralloides is one of the two dominant maerl species in England.

Lithothamnion coralloides does have a crustose permanently attached form but this has only been recorded at 2 sites in the British Isles. It is typically found as an unattached plant. Maerl has been found in densities of up to 22,000 thalli per square metre. The proportion of live to dead nodules varies considerably. As far as is known, maerl continues to grow throughout its life but fragmentation limits the size of the nodules. Individual plants may reach up to 5 cm across.

Growth rates of European maerl species range between tenths of a millimetre to one millimetre per annum (Bosence & Wilson, 2003). Recent studies suggested that the growth rates of the three most abundant species of maerl in Europe (Phymatolithon calcareum, Lithothamnion glaciale and Lithothamnion coralloides) ranged between 0.5 to 1.5 mm per tip per year under a wide range of field and laboratory conditions (Blake & Maggs, 2003). Individual maerl nodules may live for >100 years (Foster, 2001).

Long-lived maerl thalli and their dead remains build upon underlying sediments to produce deposits with a three-dimensional structure that is intermediate in character between hard and soft grounds (Jacquotte, 1962; Cabioch, 1969; Keegan, 1974; Hall-Spencer, 1998; Barbera et al., 2003). Thicker maerl beds occur in areas of water movement (wave or current based) while sheltered beds tend to be thinner with more epiphytes. The associated community varies with the underlying and surrounding sediment type, water movement, depth of bed and salinity (Tyler-Walters, 2013).

Maerl beds are highly variable and range from a thin layer of living maerl on top of a thick deposit of dead maerl to a layer of live maerl on silty or variable substratum, to a deposit of completely dead maerl or maerl debris of variable thickness. Live maerl beds vary in the depth and proportion of ‘live maerl’ present (Birkett et al., 1998a). In areas subject to wave action, they may form wave ripples or mega-ripples e.g. in Galway Bay (Keegan, 1974) and in Stravanan Bay (Hall-Spencer & Atkinson, 1999). Maerl beds also show considerable variation in water depth, the depth of the bed, and biodiversity (see Birkett et al., 1998a). Lithothamnion coralloides occurs in the south-west of England and Ireland mixed in with Phymatolithon calcareum.

Maerl exhibits a complex three-dimensional structure with interlocking lattices providing a wide range of niches for infaunal and epifaunal invertebrates (Birkett et al., 1998a). Pristine, un-impacted maerl grounds are more structurally complex than those which have been affected by dredging (Kamenos et al., 2003). The interstitial space and open structure of provided by maerl beds allows water to flow through the bed, and oxygenated water to penetrate at depth so that other species can colonize the bed to greater depths than other coarse substrata. Maerls are the pivotal, ecosystem engineer and biogenic reef species. The integrity and survival of maerl beds are dependent on the thin surface layer of living maerl (Birkett et al., 1998a; Hall-Spencer & Moore, 2000a&b).

Maerl beds are highly species rich with 150 macroalgal species and over five hundred faunal species (of which 120 are molluscs) recorded as living on or in maerl beds (Birkett et al., 1998a); see the maerl biotope SS.SMp.Mrl for further information. As far as is known, the maerl does not host any commensal or parasitic species. However, a few algae are almost entirely restricted to maerl communities e.g. the red algae Gelidiella calcicola, Gelidium maggsiae and the crustose Cruoria cruoriiformis (Birkett et al., 1998a).

Habitat preferences

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Physiographic preferences | Estuary, Open coast, Ria or Voe, Sea loch or Sea lough, Strait or Sound |

| Biological zone preferences | Lower infralittoral, Sublittoral fringe, Upper infralittoral |

| Substratum / habitat preferences | Coarse clean sand, Fine clean sand, Gravel / shingle, Maerl, Mixed, Mud, Muddy gravel, Muddy sand, Pebbles, Sandy mud |

| Tidal strength preferences | Moderately strong 1 to 3 knots (0.5-1.5 m/sec.), Strong 3 to 6 knots (1.5-3 m/sec.) |

| Wave exposure preferences | Moderately exposed, Sheltered, Very sheltered |

| Salinity preferences | Full (30-40 psu) |

| Depth range | 1-30 |

| Other preferences | No text entered |

| Migration Pattern | Non-migratory or resident |

Habitat Information

Occurs most frequently at depths between 1-10 m. Occasionally found at depths of up to 30 m (for example Outer Galway Bay).

Life history

Adult characteristics

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Reproductive type | Vegetative |

| Reproductive frequency | No information |

| Fecundity (number of eggs) | No information |

| Generation time | Insufficient information |

| Age at maturity | Not relevant |

| Season | Insufficient information |

| Life span | 20-100 years |

Larval characteristics

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Larval/propagule type | Not relevant |

| Larval/juvenile development | |

| Duration of larval stage | Not relevant |

| Larval dispersal potential | No information |

| Larval settlement period | Insufficient information |

Life history information

Maerl beds in the Sound of Iona are recorded as containing dead nodules up to 4,000 years old. Insufficient information is available on reproductive frequency, fecundity and developmental mechanism. In Britain there is only one record of a fertile plant (found in July). Consequently virtually all propagation must be presumed to be vegetative and therefore dispersal potential is recorded as low. Plants from Brittany are mostly fertile in winter but Adey and McKibbin (1970) recorded a plant from Spain being fertile in August. Cabioch (1969) suggested Lithothamnion corallioides may have phasic reproduction with peaks every six years. This may account for observed changes in the relative proportions of live Lithothamnion corallioides and Phymatolithon calcareum nodules in maerl beds. Dominance cycles with periods of about thirty years have been recorded on some of the maerl beds of northern Brittany.Sensitivity review

Resilience and recovery rates

Maerl thalli, including Lithothamnion coralloides, grow very slowly (Adey & McKibbin, 1970; Potin et al., 1990; Littler et al., 1991; Hall-Spencer, 1994; Birkett et al., 1998a Hall-Spencer & Moore, 2000a,b) so that maerl deposits may take hundreds of years to develop, especially in high latitudes (BIOMAERL, 1998). Growth rates of European maerl species range between tenths of a millimetre to one millimetre per annum (Bosence & Wilson, 2003). Recent studies suggested that the growth rates of the three most abundant species of maerl in Europe (Phymatolithon calcareum, Lithothamnion glaciale and Lithothamnion coralloides) ranged between 0.5 to 1.5 mm per tip per year under a wide range of field and laboratory conditions (Blake & Maggs, 2003).

Individual maerl nodules may live for >100 years (Foster, 2001). Maerl beds off Brittany are over 5500 years old (Grall & Hall-Spencer, 2003) and the maerl bed at St Mawes Bank, Falmouth was estimated to have a maximum age of 4000 years (Bosence & Wilson, 2003) while carbon dating suggested that some established beds may be 4000 to 6000 years old (Birkett et al., 1998a). The maerl bed in the Sound of Iona was recorded to be ˂4000 years old (Hall-Spencer et al., 2003). Maerl is highly sensitive to damage from any source due to this very slow rate of growth (Hall-Spencer, 1998). Maerl is also very slow to recruit as it rarely produces reproductive spores. Little information is available on reproductive frequency, fecundity and developmental mechanism. Maerl is considered to be a non-renewable resource due to its very slow growth rate and its inability to sustain direct exploitation (Barbera et al., 2003; Wilson et al., 2004).

Maerl species in the UK are known to propagate mainly by fragmentation (Wilson et al., 2004). There are no detailed studies about reproduction in which Lithothamnion coralloides. It important to note that newly settled maerl thalli have never been found in the British Isles (Irvine & Chamberlain, 1994). Hall-spencer (2009) suggested that a live maerl bed would take 1000’s of years to return to the site of navigation channel after planned capital dredging in the Fal estuary. He also suggested that it would take 100’s of years for live maerl to grow on a translocated bed, based on the growth and accumulation rates of maerl given by Blake et al. (2007) (Hall-Spencer, 2009).

Resilience assessment. The current evidence regarding the recovery of maerl suggests that if maerl is removed, fragmented or killed then it has almost no ability to recover. Therefore, resilience is assessed as ‘Very low’ and probably far exceeds the minimum of 25 years for this category on the scale in cases where the resistance is 'Medium', ‘Low’ or ‘None’.

Note. The resilience and the ability to recover from human induced pressures is a combination of the environmental conditions of the site, the frequency (repeated disturbances versus a one-off event) and the intensity of the disturbance. Recovery of impacted populations will always be mediated by stochastic events and processes acting over different scales including, but not limited to, local habitat conditions, further impacts and processes such as larval supply and recruitment between populations. Full recovery is defined as the return to the state of the habitat that existed prior to impact. This does not necessarily mean that every component species has returned to its prior condition, abundance or extent but that the relevant functional components are present and the habitat is structurally and functionally recognisable as the initial habitat of interest. It should be noted that the recovery rates are only indicative of the recovery potential.

Hydrological Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Temperature increase (local) [Show more]Temperature increase (local)Benchmark. A 5°C increase in temperature for one month, or 2°C for one year. Further detail EvidenceMaerl beds in the north-east Atlantic range from Norway to the African coast, although the component maerl species vary in temperature tolerance (Birkett et al., 1998a, Wilson et al., 2004). Lithothamnion coralloides is absent from Scottish waters. This is due, either to winter temperatures dropping below the minimum survival temperature (between 2 –5°C) or because the temperatures don’t allow a suitable growing season (Adey & McKibbin, 1970; cited in Wilson et al., 2004). Adey & McKibbin (1970) recorded an optimum temperature of 10°C for Lithothamnion coralloides, with growth showing a gradual reduction up until 20°C, where it stops completely. Martin et al. (2006) reported that primary productivity in Lithothamnion corallioides was twice as high in August as in January to February in the Bay of Brest. They found that primary productivity, calcification and respiration rates of Lithothamnion corallioides increased as temperature rose from 10 to 16°C (Martin et al., 2006). Maerl species appear to have wide geographic ranges and are likely to be tolerant of higher temperatures than those experienced in the British Isles. The range of Lithothamnion coralloides may not accurately describe its ability to withstand localized changes in temperature, as it may be acclimatized to local conditions. However, the range of species may to some extent display the limits of the species genetic ability to acclimatize to temperatures. Lithothamnion corallioides is a warm temperate species ranging from Ireland and the south of Britain to the Mediterranean, while Lithothamnion glaciale and Lithothamnion erinaceum are cold temperate species that replace Lithothamnion corallioides in northern waters of the UK and the North East Atlantic (Melbourne et al., 2017). Martin & Hall-Spencer (2017) noted that a 3°C increase in temperature above that normally experienced by tropical or warm-temperate coralline algae caused bleaching and adversely affected heath, rates of calcification and photosynthesis and survival. Current trends in climate change driven temperature increases have already caused shifts in seaweed biogeography, as the tropical regions widen polewards, to the detriment of the warm-temperate region, and the cold-temperate region shrinks (Martin & Hall-spencer, 2017). Sensitivity assessment. An increase in temperature at the benchmark level may affect Lithothamnion coralloides. It has a more southern distribution in the UK and may benefit from a localised temperature increase, so that the relative abundance of Lithothamnion coralloides may change in the long-term compared to other maerl forming species. However, given the slow growth rates exhibited by Lithothamnion coralloides, no effect is likely to be perceived within the duration of the benchmark, but long-term climate change effects may be noticed in future. Therefore, Lithothamnion coralloides probably has a ‘High’ resistance to an increase in temperature at the benchmark level. Resilience is, therefore, ‘High’ and an assessment of ‘Not sensitive’ at the benchmark level is recorded. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Temperature decrease (local) [Show more]Temperature decrease (local)Benchmark. A 5°C decrease in temperature for one month, or 2°C for one year. Further detail EvidenceMaerl beds in the north-east Atlantic range from Norway to the African coast, although the component maerl species vary in temperature tolerance (Birkett et al., 1998a; Wilson et al., 2004). Lithothamnion coralloides is absent from Scottish waters (Adey & McKibbin, 1970). This is due, either to winter temperatures dropping below the minimum survival temperature (between 2 – 5°C) or because the temperatures don’t allow a suitable growing season (Adey & McKibbin, 1970; Wilson et al., 2004). During laboratory experiments, aquaria temperatures were reduced from 10°C to 0.4°C or 0.2°C (depending on light intensity and light: dark cycle) over a period of two to eight weeks. After the period of temperature reduction, all samples of Lithothamnion coralloides were dead. Specimens in aquaria where temperatures had only been reduced to 2.1°C also died. However, samples kept at 5°C survived without growth (Adey & McKibbin 1970). In the same study, 10°C was recorded as the optimum temperature for this species (Adey & McKibbin 1970). Martin et al. (2006) reported that primary productivity in Lithothamnion corallioides was twice as high in August as in January to February in the Bay of Brest. They found that primary productivity, calcification and respiration rates of Lithothamnion corallioides increased as temperature rose from 10 to 16°C (Martin et al., 2006). The range of Lithothamnion coralloides may not accurately describe its ability to withstand localized changes in temperature, as it may be acclimatized to local conditions. However, the range of species may to some extent display the limits of the species genetic ability to acclimatize to temperatures. Lithothamnion corallioides is a warm temperate species ranging from Ireland and the south of Britain to the Mediterranean, while Lithothamnion glaciale and Lithothamnion erinaceum are cold temperate species that replace Lithothamnion corallioides in northern waters of the UK and the North East Atlantic (Melbourne et al., 2017). Sensitivity assessment. A decrease in temperature at the benchmark may be detrimental to Lithothamnion coralloides, which is restricted to southern waters in the UK, especially at the northernmost extent of its range. A decrease in temperature of 2°C for a year is likely to reduce growth and reproduction in Lithothamnion coralloides, although there was no information on the effect of a decrease of 5°C for one month. Therefore, a resistance of ‘Medium’ is suggested at the benchmark level to represent the possible reduction in abundance at its northernmost extent, but with 'Low' confidence. Resilience is, therefore ‘Very low’, and sensitivity is assessed as ‘Medium’. | MediumHelp | Very LowHelp | MediumHelp |

Salinity increase (local) [Show more]Salinity increase (local)Benchmark. A increase in one MNCR salinity category above the usual range of the biotope or habitat. Further detail EvidenceThe majority of maerl species occur in full salinity. Joubin (1910 cited in Wilson et al., 2004) thought that maerl beds were only present in areas with lowered salinity. Bosence (1976) found that although surface salinities could be low, the benthic water was mostly fully saline. Wilson et al. (2004) noted that Lithothamnion coralloides was tolerant up to 40 psu. Sensitivity assessment. An increase in salinity above full is unlikely, except via the discharge of hypersaline effluents from desalination plants. Where Lithothamnion coralloides is found in areas of reduced or variable salinity, an increase in salinity is unlikely to have an effect. Any increase in the salinity regime which results in hypersaline conditions is likely to have a significant negative impact on Lithothamnion coralloides. No species of maerl naturally occur within hypersaline areas, and although it may be able to tolerate a short-term increase in salinity, an increase to hypersaline conditions for a year would cause significant negative impacts. However, ‘no evidence’ was available on which to base an assessment. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Salinity decrease (local) [Show more]Salinity decrease (local)Benchmark. A decrease in one MNCR salinity category above the usual range of the biotope or habitat. Further detail EvidenceThe majority of maerl species occur in full salinity. Although Joubin, (1910, cited in Wilson et al., 2004) thought that maerl beds were only present in areas with lowered salinity. Bosence (1976) found that although surface salinities could be low, the benthic water was mostly fully saline. Lithothamnion coralloides is recorded from areas with ‘full’ salinity regimes. Adey & McKibbin (1970) slowly lower the salinity of specimens of Lithothamnion coralloides (grown for two months at 33.5 ppt in the laboratory) to 23 ppt for a month, and then to 13 ppt for another two weeks. Lithothamnion coralloides stopped growing at 24 ppt but on return to full salinity, resumed growth after a month and appeared healthy. Adey & McKibbin (1970) suggested that low salinity had 'little lethal importance' but that low salinity may 'have an adverse effect on growth', especially in enclosed estuaries with 'large' streams. Sensitivity assessment. Therefore, a decrease in salinity from ‘full’ to reduced’ conditions’ is unlikely to have an adverse effect. However, a decrease from ‘reduced’ to ‘low’ may result in reduced growth and potentially death of the maerl over a period of a year. Hence, a resistance of ‘Medium’ is suggested but with 'Low' confidence. Resilience is probably ‘Very low’ so that a sensitivity of 'Medium' is recorded. | MediumHelp | Very LowHelp | MediumHelp |

Water flow (tidal current) changes (local) [Show more]Water flow (tidal current) changes (local)Benchmark. A change in peak mean spring bed flow velocity of between 0.1 m/s to 0.2 m/s for more than one year. Further detail EvidenceMaerl species, including Lithothamnion coralloides, require a degree of shelter from wave action to prevent burial and dispersal into deep water. However, they also need enough water movement to prevent smothering with silt (Hall-Spencer, 1998). Therefore, maerl is restricted to areas of strong tidal currents or wave oscillation (Birkett et al. 1998a). For example, Birkett et al. (1998a) quote a flow rate of 0.1m / s across the maerl bed at spring tides in Greatman’s Bay, Galway, while the UK biotope classification (Connor et al., 2004) reports maerl species occurring at sites with between moderately strong to very weak tidal streams. As Birkett et al. (1998a) note, local topography and wave generated oscillation probably result in stronger local currents at the position of the bed. However, Hall-Spencer et al. (2006) reported that maerls beds in the vicinity of fish farms became silted with particulates from fish farms even in areas of strong flow. Hall-Spencer et al. (2006) reported peak flow rates of 0.5 to 0.7 m/s at the sites studied, and one site experienced mean flows of 0.11 to 0.12 m/s and maxima of 0.21 to 0.47 m/s depending on depth above the seabed. Sensitivity assessment. An increase in water flow to strong or very strong may winnow away the surface of the bed and result in loss of the live layer of Lithothamnion coralloides. Similarly, a decrease in water flow may result in increased siltation, smothering maerl and filling the bed with silt, causing the death of maerl (see smothering/siltation below). So the effect will depend on local hydrography and the wave climate. A change of 0.1-0.2 m/s is unlikely to have a significant effect. However, Hall-spencer (pers. comm.) noted that any change in water flow is likely to affect maerl beds. Therefore, a resistance of 'Low' is suggested but with 'Low' confidence. Hence, as resilience is likely to be 'Very low', sensitivity is assessed as 'High'. | LowHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Emergence regime changes [Show more]Emergence regime changesBenchmark. 1) A change in the time covered or not covered by the sea for a period of ≥1 year or 2) an increase in relative sea level or decrease in high water level for ≥1 year. Further detail EvidenceIn the UK, Lithothamnion coralloides is recorded from shallow depths. Maerl is highly sensitive to desiccation (Wilson et al., 2004), and live maerl does survive in the intertidal. However, it is very unlikely that a maerl bed would be exposed at low water as a result of human activities or natural events (Tyler-Walters, 2013). Therefore, this pressure is probably ‘Not relevant’. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Wave exposure changes (local) [Show more]Wave exposure changes (local)Benchmark. A change in near shore significant wave height of >3% but <5% for more than one year. Further detail EvidenceMaerl requires a degree of shelter from wave action, to prevent burial and dispersal into deep water. However, they also need enough water movement to prevent smothering with silt (Hall-Spencer, 1998). Therefore, maerl develops in strong currents but are restricted to areas of low wave action. For example, in Mannin Bay dense maerl beds were restricted to less wave exposed parts of the bay (Birkett et al., 1998a). Areas of maerl subject to wave action often show mobile areas in the form of ripples or mega-ripples (Keegan, 1974; Hall-Spencer & Atkinson, 1999). In Galway Bay, Keegan (1974) noted the formation of ripples due to wave action and storms, where the ripples were flattened over time by tidal currents. Hall-Spencer & Atkinson (1999) noted that mega-ripples at their wave exposed site were relatively stable but underwent large shifts due to storms. However, the mixed sediments of the subsurface of the bed (>12 cm) were unaffected so that the burrows of the mud shrimp remained in place. Similarly, Birkett et al. (1998a) noted that in areas where storms affected the maerl at a depth of 10 m, only the coarse upper layer of maerl was moved while the underlying layers were stable. Infaunal species renewed burrow linings within a week after storms. Deep beds are less likely to be affected by an increase in wave exposure. Sensitivity assessment. Lithothamnion coralloides occurs in a range of wave exposures and can survive in areas subject to wave action and even storms, if deep enough. Therefore, an increase in wave exposure is probably detrimental to Lithothamnion coralloides in shallow waters. Similarly, a decrease in wave action may be detrimental where wave action is the main contribution to water movement through the bed, due to the potential increase of siltation. However, a 3-5% change in significant wave height is unlikely to be significant. Both resistance and resilience are assessed as ‘High’, and Lithothamnion coralloides is assessed as ‘Not sensitive’ to this pressure at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Chemical Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Transition elements & organo-metal contamination [Show more]Transition elements & organo-metal contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Hydrocarbon & PAH contamination [Show more]Hydrocarbon & PAH contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Synthetic compound contamination [Show more]Synthetic compound contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Radionuclide contamination [Show more]Radionuclide contaminationBenchmark. An increase in 10µGy/h above background levels. Further detail Evidence‘No evidence’. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Introduction of other substances [Show more]Introduction of other substancesBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

De-oxygenation [Show more]De-oxygenationBenchmark. Exposure to dissolved oxygen concentration of less than or equal to 2 mg/l for one week (a change from WFD poor status to bad status). Further detail EvidenceDeoxygenation at the benchmark level is likely to be detrimental to the maerl beds and their infaunal community but mitigated. Water flow experienced by these biotopes suggests that deoxygenating conditions may be short-lived. However, Hall-Spencer et al. (2006) examined maerl beds in the vicinity of fish farms in strongly tidal areas. They noted a build-up of waste organic materials up to 100 m from the farms examined and a 10-100 fold increase in scavenging fauna (e.g. crabs). In the vicinity of the farm cages, the biodiversity was reduced, particularly of small crustaceans, with significant increases in species tolerant of organic enrichment (e.g. Capitella). In addition, they reported less live maerl around all three of the fish farm sites studied than the 50-60% found at reference sites. Most of the maerl around fish farms in Orkney and South Uist was dead and clogged with black sulphurous anoxic silt. The Shetland farm had the most live maerl but this was formed into mega-ripples, indicating that the maerl had been transported to the site by rough weather (Hall-Spencer et al., 2006). Eutrophication resulting from aquaculture is cited as one reason for the decline of maerl beds in the North East Atlantic (Hall-Spencer et al., 2010). In the laboratory, Wilson et al. (2004) noted that burial in black muddy sand, smelling of hydrogen sulphide, was fatal to live maerl. Even thalli placed on the surface of the black muddy sand died within two weeks, together with thalli buried by 0.25 cm and 2 cm of the sediment (Wilson et al., 2004). A study of a phytoplankton bloom that killed herring eggs on a maerl bed in the Firth of Clyde found that the resultant anoxia caused mass mortalities of the burrowing infauna (Napier, in press, cited by Hall-Spencer pers comm.). Sensitivity assessment. The available evidence suggests that maerl and its associated community is sensitive to the effects of deoxygenation and anoxia, even in areas of strong water movement. Therefore, resistance has been assessed as ‘Low’, resilience as ‘Very low’, and sensitivity is assessed as ‘High’. | LowHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Nutrient enrichment [Show more]Nutrient enrichmentBenchmark. Compliance with WFD criteria for good status. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure relates to increased levels of nitrogen, phosphorus and silicon in the marine environment compared to background concentrations. The nutrient enrichment of a marine environment leads to organisms no longer being limited by the availability of certain nutrients. The consequent changes in ecosystem functions can lead to the progression of eutrophic symptoms (Bricker et al., 2008), changes in species diversity and evenness (Johnston & Roberts, 2009) decreases in dissolved oxygen and uncharacteristic microalgal blooms (Bricker et al., 1999, 2008). In Brittany, numerous maerl beds were affected by sewage outfalls and urban effluent, resulting in increases in contaminants, suspended solids, microbes and organic matter with resultant deoxygenation (Grall & Hall-Spencer, 2003). This resulted in increased siltation, higher abundance and biomass of opportunistic species, and loss of sensitive species. Grall & Hall-Spencer (2003) note that two maerl beds directly under sewage outfalls were converted from dense deposits of live maerl in the 1950s to heterogeneous mud with maerl fragments buried under several centimetres of fine sediment with species poor communities. These maerl beds were effectively lost. Sensitivity assessment. The effect of eutrophication on maerl is difficult to disentangle from the effects of organic enrichment, and sedimentation. However, the nutrient load from sewage outfalls and urban runoff is likely to be higher than the benchmark level. Hence, Lithothamnion coralloides is considered to be ‘Not sensitive’ at the pressure benchmark of compliance with WFD criteria for good status. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not sensitiveHelp |

Organic enrichment [Show more]Organic enrichmentBenchmark. A deposit of 100 gC/m2/yr. Further detail EvidenceThe organic enrichment of a marine environment at this pressure benchmark leads to organisms no longer being limited by the availability of organic carbon. The consequent changes in ecosystem functions can lead to the progression of eutrophic symptoms (Bricker et al., 2008), changes in species diversity and evenness (Johnston & Roberts, 2009) and decreases in dissolved oxygen and uncharacteristic microalgae blooms (Bricker et al., 1999, 2008). Grall & Hall-Spencer (2003) considered the impacts of eutrophication as a major threat to maerl beds. Hall-Spencer et al. (2006) compared maerl beds under salmon farms with reference maerl beds. It was found that maerl beds underneath salmon farms had visible signs of organic enrichment (feed pellets, fish faeces and/or Beggiatoa mats), and significantly lower biodiversity. At the sites underneath the salmon nets, there were 10 – 100 times the number of scavenging species present compared to the reference sites. Grall & Glémarec (1997) noted similar decreases in maerl bed biodiversity due to anthropogenic eutrophication in the Bay of Brest. In Brittany, numerous maerl beds were affected by sewage outfalls and urban effluent, resulting in increases in contaminants, suspended solids, microbes and organic matter with resultant deoxygenation (Grall & Hall-Spencer, 2003). This resulted in increased siltation, higher abundance and biomass of opportunistic species, loss of sensitive species and reduction in biodiversity. Grall & Hall-Spencer (2003) note that two maerl beds directly under sewage outfalls were converted from dense deposits of live maerl in the 1950s to heterogeneous mud with maerl fragments buried under several centimetres of fine sediment with species poor communities. These maerl beds were effectively lost. Sensitivity assessment. Little empirical evidence was found to directly compare the benchmark organic enrichment to Lithothamnion coralloides. However, the evidence suggests that organic enrichment and resultant increased in organic content, hydrogen sulphide levels and sedimentation may result in loss of maerl. Resistance has been assessed as ‘None’, resilience as ‘Very low’ and sensitivity assessed as ‘High’. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Physical Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Physical loss (to land or freshwater habitat) [Show more]Physical loss (to land or freshwater habitat)Benchmark. A permanent loss of existing saline habitat within the site. Further detail EvidenceAll marine benthic species are considered to have a resistance of ‘None’ to this pressure and to be unable to recover from a permanent loss of habitat (resilience is ‘Very Low’). Sensitivity within the direct spatial footprint of this pressure is, therefore ‘High’. Although no specific evidence is described, confidence in this assessment is ‘High’, due to the incontrovertible nature of this pressure. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Physical change (to another seabed type) [Show more]Physical change (to another seabed type)Benchmark. Permanent change from sedimentary or soft rock substrata to hard rock or artificial substrata or vice-versa. Further detail EvidenceLithothamnion coralloides can contain a variety of sediment types including gravel, shingle and other coarse sediments but never bedrock. Therefore, if rock or an artificial substratum were to replace the normal substratum that this species is found on then the species would not be able to survive. Resistance is likely to be ‘None’, resilience is ‘Very low’ (permanent change) and sensitivity is assessed as ‘High’. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Physical change (to another sediment type) [Show more]Physical change (to another sediment type)Benchmark. Permanent change in one Folk class (based on UK SeaMap simplified classification). Further detail EvidenceThe sediment often found underneath Lithothamnion coralloides can vary from shell and gravel through to gravel and shingle. Lithothamnion coralloides is also not attached to the substratum, and instead, lies over the top of it. Therefore, if the substratum were to change this wouldn’t have a negative effect on the species. Sensitivity assessment. A change in this pressure at the benchmark will not affect Lithothamnion coralloides. Resistance and resilience are assessed as ‘High’, resulting in an assessment of ‘Not Sensitive’. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Habitat structure changes - removal of substratum (extraction) [Show more]Habitat structure changes - removal of substratum (extraction)Benchmark. The extraction of substratum to 30 cm (where substratum includes sediments and soft rock but excludes hard bedrock). Further detail EvidenceThe extraction of the substratum to 30 cm would remove almost all of the Lithothamnion coralloides (live and dead), within the footprint of the activity. Sensitivity assessment. The resistance of Lithothamnion coralloides to this pressure at the benchmark is ‘None’, the resilience is assessed as ‘Very low’ and sensitivity is assessed as ‘High’. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Abrasion / disturbance of the surface of the substratum or seabed [Show more]Abrasion / disturbance of the surface of the substratum or seabedBenchmark. Damage to surface features (e.g. species and physical structures within the habitat). Further detail EvidencePhysical disturbance can result from; channelization (capital dredging), suction dredging for bivalves, extraction of maerl, scallop dredging or demersal trawling. The effects of physical disturbance were summarised by Birkett et al. (1998a) and Hall-Spencer et al. (2010), and documented by Hall-Spencer and co-authors (Hall-Spencer, 1998; Hall-Spencer et al., 2003; Hall-Spencer & Moore, 2000a, b; Hauton et al., 2003; and others). For example, in experimental studies, Hall-Spencer & Moore (2000a, c) reported that the passage of a single scallop dredge through a maerl bed could bury and kill 70% of living maerl in its path. The passing dredge also re-suspended sand and silt that settled over a wide area (up to 15 m from the dredged track) and smothered the living maerl. Abrasion may break up Lithothamnion coralloides nodules into smaller pieces resulting in easier displacement by wave action, and a reduced structural heterogeneity and lower biodiversity(Kamenos et al., 2003). Sensitivity assessment. Physical disturbance can result in the fragmentation of Lithothamnion coralloides but will not kill it directly. Subsequent death is likely due to a reduction in water flow caused by compaction and sedimentation (Hall-spencer & Moore, 2000a; 2000c; Kamenos et al., 2003). Dredging can create plumes of sediment that can settle on top of the maerl, and overturn and bury maerl, causing it to be smothered, a pressure to which maerl is not resistant (see 'smothering' and 'siltation' pressures). The evidence from Hall-Spencer & Moore (2000a; 2000 c) alone strongly suggests that resistance to physical disturbance and abrasion is ‘Low’. Therefore, resilience is probably ‘Very low’, resulting in a sensitivity assessment of ‘High’. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Penetration or disturbance of the substratum subsurface [Show more]Penetration or disturbance of the substratum subsurfaceBenchmark. Damage to sub-surface features (e.g. species and physical structures within the habitat). Further detail EvidenceThe fragmentation of Lithothamnion coralloides will not directly cause mortality of the organism. However, the smaller pieces will be lighter and, therefore, more likely to be entrained and exported in the strong tidal flows characteristic of where Lithothamnion coralloides is found. Nevertheless, the evidence provided within the 'abrasion and disturbance' pressure (above) suggests that maerl is not resistant of the abrasion of any form. Penetration of the maerl bed will only exacerbate the negative effect by damaging more of the underlying maerl. Sensitivity assessment. Based on the evidence provided within the 'abrasion and disturbance' assessment (above) the resistance of the Lithothamnion coralloides to this pressure at the benchmark is considered ‘None’ and the resilience is assessed as ‘Very low’ and the sensitivity of Lithothamnion coralloides is assessed as ‘High’. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Changes in suspended solids (water clarity) [Show more]Changes in suspended solids (water clarity)Benchmark. A change in one rank on the WFD (Water Framework Directive) scale e.g. from clear to intermediate for one year. Further detail EvidenceLithothamnion coralloides requires light, and is, therefore, restricted to depths shallower than 10 m in the relatively turbid waters of northern Europe (Hall-Spencer, 1998). An increase in suspended sediments in the water column will increase light attenuation and decrease the availability of light. A decrease in light availability will alter the ability of the maerl to photosynthesise. This could be detrimental to Lithothamnion coralloides found towards the bottom of its depth limit in Europe (i.e. 10 m). An increase in suspended solids is also likely to increase scour, as there are characteristically high levels of water movement in maerl habitat. Scour is known to induce high mortality in early post-settlement algal stages and prevents the settlement of propagules owing to the accumulation of silt on the substratum (Vadas et al., 1992). A decrease in suspended solids will increase light levels, which could benefit maerl. Sensitivity assessment. Any factor which may decrease the ability for Lithothamnion coralloides to photosynthesise will have a negative impact. Where this species is found at the very bottom depth limit may experience high levels of mortality. The resistance of this species is considered to be ‘Medium’ and the resilience is ‘Very low’. This gives the species an overall sensitivity of ‘Medium’ to the pressure at the benchmark. | MediumHelp | Very LowHelp | MediumHelp |

Smothering and siltation rate changes (light) [Show more]Smothering and siltation rate changes (light)Benchmark. ‘Light’ deposition of up to 5 cm of fine material added to the seabed in a single discrete event. Further detail EvidenceSmothering results from the rapid deposition of sediment or spoil, which may occur after dredging (suction or scallop), capital dredging (channelization), extreme runoff, spoil dumping etc. The effects depend on the nature of the smothering sediment. For example, live maerl was found to survive burial in coarse sediment (Wilson et al., 2004) but to die in fine sediments. Phymatolithon calcareum, another maerl species very similar to Lithothamnion coralloides survived for four weeks buried under 4 and 8 cm of sand or gravel but died within 2 weeks under 2 cm of muddy sand. Wilson et al. (2004) suggested that the hydrogen sulphide content of the muddy sand was the most detrimental aspect of burial since even those maerl nodules on the surface of the muddy sand died within two weeks. They also suggested that the high death rate of maerl observed after burial due to scallop dredging (Hall-Spencer & Moore, 2000a,c) was probably due to physical and chemical effects of burial rather than a lack of light (Wilson et al., 2004). In Galicia, France, ongoing deterioration of maerl has been linked to mussel farming that increases sedimentation, reducing habitat complexity, lowering biodiversity, and killing maerl (Pena & Barbara, 2007a, b; cited in Hall-Spencer et al., 2010). Wilson et al. (2004) also point out that the toxic effect of fine organic sediment and associated hydrogen sulphide explain the detrimental effect on maerl beds of Crepidula fornicata in Brittany, sewage outfalls, and aquaculture (Grall & Hall-spencer, 2003). Sensitivity assessment. Even though Lithothamnion coralloides occurs in areas of tidal or wave mediated water flow, smothering by fine material could penetrate the open matrix of the maerl bed rather than sit on top of the bed. At the pressure benchmark (5 cm of fine material) Lithothamnion coralloides’ resistance is assessed as ‘None’, and the resilience is ‘Very low’, resulting in an overall sensitivity of ‘High’. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Smothering and siltation rate changes (heavy) [Show more]Smothering and siltation rate changes (heavy)Benchmark. ‘Heavy’ deposition of up to 30 cm of fine material added to the seabed in a single discrete event. Further detail EvidenceA deposit at the pressure benchmark (30 cm) would cover Lithothamnion coralloides with a thick layer of fine materials. The pressure is significantly higher than light smothering discussed above. Therefore, resistance is assessed as ‘None’, and the resilience is ‘Very low’, resulting in an overall sensitivity of ‘High’. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Litter [Show more]LitterBenchmark. The introduction of man-made objects able to cause physical harm (surface, water column, seafloor or strandline). Further detail Evidence‘Not assessed’. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Electromagnetic changes [Show more]Electromagnetic changesBenchmark. A local electric field of 1 V/m or a local magnetic field of 10 µT. Further detail Evidence‘No evidence’. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Underwater noise changes [Show more]Underwater noise changesBenchmark. MSFD indicator levels (SEL or peak SPL) exceeded for 20% of days in a calendar year. Further detail Evidence‘Not relevant’. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Introduction of light or shading [Show more]Introduction of light or shadingBenchmark. A change in incident light via anthropogenic means. Further detail EvidenceLithothamnion coralloides has a requirement for light which restricts it to depths shallower than 10 m, suggesting that maerl is intolerant of long-term reductions in light availability. However, in the short-term maerl exhibits little stress after being kept in the dark for 4 weeks (Wilson et al., 2004). Sensitivity assessment. Artificial light is unlikely to affect any but Lithothamnion coralloides in the shallowest conditions. There is a possibility that shading by artificial structures could result in the loss if Lithothamnion coralloides is found at its most extreme depths, but only where shading was long-term or permanent. There is insufficient information to assess the effect of this pressure at the benchmark on this species. Therefore, ‘No evidence’ is recorded. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Barrier to species movement [Show more]Barrier to species movementBenchmark. A permanent or temporary barrier to species movement over ≥50% of water body width or a 10% change in tidal excursion. Further detail Evidence‘Not relevant’ – this pressure is considered applicable to mobile species, e.g. fish and marine mammals rather than seabed habitats. Physical and hydrographic barriers may limit propagule dispersal. But propagule dispersal is not considered under the pressure definition and benchmark. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Death or injury by collision [Show more]Death or injury by collisionBenchmark. Injury or mortality from collisions of biota with both static or moving structures due to 0.1% of tidal volume on an average tide, passing through an artificial structure. Further detail Evidence‘Not relevant’ to seabed habitats. NB. Collision by grounding vessels is addressed under ‘surface abrasion’. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Visual disturbance [Show more]Visual disturbanceBenchmark. The daily duration of transient visual cues exceeds 10% of the period of site occupancy by the feature. Further detail Evidence‘Not relevant’. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Biological Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Genetic modification & translocation of indigenous species [Show more]Genetic modification & translocation of indigenous speciesBenchmark. Translocation of indigenous species or the introduction of genetically modified or genetically different populations of indigenous species that may result in changes in the genetic structure of local populations, hybridization, or change in community structure. Further detail Evidence‘No evidence’ of genetic modification and/or translocation was found. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Introduction or spread of invasive non-indigenous species [Show more]Introduction or spread of invasive non-indigenous speciesBenchmark. The introduction of one or more invasive non-indigenous species (INIS). Further detail EvidenceNo evidence of the effects of non-indigenous invasive species in UK waters was found. However, Grall & Hall-spencer (2003) note that beds of invasive slipper limpet Crepidula fornicata grew across maerl in Brittany. As a result, the maerl thalli were killed, and the bed clogged with silt and pseudofaeces so that the associated community was drastically changed. Bivalve fishing was also rendered impossible. Peña et al. (2014) identified eleven invasive algal species found on maerl beds in the North East Atlantic. The invasive species included Sargassum muticum, which causes habitat shading (Hall-Spencer pers. comm.). Sensitivity assessment. Removal of the surface layer of Crepidula fornicata is possible but only with the removal of the surface layer of Lithothamnion coralloides itself, which in itself would be extremely destructive. A resistance of ‘None’ and a resilience of ‘Very low’ have been recorded, resulting in an overall sensitivity assessment of ‘High’. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Introduction of microbial pathogens [Show more]Introduction of microbial pathogensBenchmark. The introduction of relevant microbial pathogens or metazoan disease vectors to an area where they are currently not present (e.g. Martelia refringens and Bonamia, Avian influenza virus, viral Haemorrhagic Septicaemia virus). Further detail EvidenceCoralline lethal orange disease is found in the Pacific and could have devastating consequences for Lithothamnion coralloides. However, this disease was not known to be in Europe (Birkett et al., 1998a) and ‘No evidence’ of the effects of diseases and pathogens on Lithothamnion coralloides could be found. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Removal of target species [Show more]Removal of target speciesBenchmark. Removal of species targeted by fishery, shellfishery or harvesting at a commercial or recreational scale. Further detail EvidenceLithothamnion coralloides can be sold dried as a soil additive but is also used in animal feed, water filtration systems, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and bone surgery. Maerl beds containing Lithothamnion coralloides are dredged for scallops (found in high densities compared with other scallop habitats) where extraction efficiency is very high. This harvesting has serious detrimental effects on the diversity, species richness and abundance of maerl beds (BIOMAERL team, 1999). Within Europe, there is a history of the commercial collection and sale of maerl. Two notable sites from western Europe from which maerl was collected were off the coast of Brittany, where 300,000 – 500,000 t / annum were dredged (Blunden, 1991), and off Falmouth Harbour in Cornwall where extraction was around 20,000 t / annum (Martin, 1994; Hall-Spencer, 1998). However, maerl extraction was banned in the Fal in 2005 (Hall-Spencer et al., 2010). Kamenos et al. (2003) reported that maerl grounds impacted by towed demersal fishing gears are structurally less heterogeneous than pristine, un-impacted maerl grounds, diminishing the biodiversity potential of these habitats. Birkett et al. (1998a) noted that although maerl beds subject to extraction in the Fal estuary exhibit a diverse flora and fauna, they were less species-rich than those in Galway Bay, although direct correlation with dredging was unclear. Grall & Glemarec (1997; cited in Birkett et al., 1998a) reported few differences in biological composition between exploited and control beds in Brittany. Dyer & Worsfold (1998) showed differences in the communities present in exploited, previously exploited and unexploited areas of maerl bed in the Fal Estuary but it was unclear if the differences were due to extraction or the hydrography and depth of the maerl beds sampled. In Brittany, many of the maerl beds are subject to extraction (Grall & Hall-Spencer, 2003). For example, the clean maerl gravel of the Glenan maerl bank described in 1969 was degraded to muddy sand dominated by deposit feeders and omnivores within 30 years. Grall & Hall-Spencer (2003) noted that the bed would be completed removed within 50-100 years at the rates reported in their study. Sensitivity assessment. Maerl, including Lithothamnion coralloides, has historically been targeted for commercial collection. Lithothamnion coralloides has no ability to avoid removal, and therefore, resistance is assessed as ‘None’, and the resilience is assessed as ‘Very low’, and sensitivity is assessed as ‘High’. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Removal of non-target species [Show more]Removal of non-target speciesBenchmark. Removal of features or incidental non-targeted catch (by-catch) through targeted fishery, shellfishery or harvesting at a commercial or recreational scale. Further detail EvidenceDirect, physical impacts from harvesting are assessed through the abrasion and penetration of the seabed pressures. Lithothamnion coralloides could easily be incidentally removed as by-catch when other species are being targeted (e.g. via scallop dredging), see ‘removal of target species’ and ‘abrasion’ pressures above. Sensitivity assessment. The resistance to non-targetted removal is ‘Low’ due to the inability of Lithothamnion coralloides to evade collection. The resilience is ‘Very low’, with recovery only being able to begin when the harvesting pressure is removed altogether. Hence, sensitivity is assessed as ‘High’. | LowHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Importance review

Policy/legislation

| Designation | Support |

|---|---|

| UK Biodiversity Action Plan Priority | Yes |

| Species of principal importance (England) | Yes |

| Species of principal importance (Wales) | Yes |

| Features of Conservation Importance (England & Wales) | Yes |

Status

| National (GB) importance | Nationally scarce | Global red list (IUCN) category | - |

Non-native

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Native | Native |

| Origin | - |

| Date Arrived | - |

Importance information

Maerl forms a very complex structure and provides a substratum for other species as well as crevices and shelter. Maerl beds are highly species rich with 150 macroalgal species and over five hundred faunal species (of which 120 are molluscs) recorded as living on or in maerl beds (Birkett et al., 1998a; Hall-spencer, 1998). Hall-Spencer et al. (2003) note that maerl beds are feeding areas for juvenile Atlantic cod, and host reserves of brood stock for razor shells Ensis spp., the great scallop Pecten maximus and the warty venus Venus verrucosa. and it may provide nursery areas for commercially important species of bivalves e.g. scallops (see the maerl biotope SS.SMp.Mrl for further information).

Maerl beds off Brittany are over 5500 years old (Grall & Hall-Spencer, 2003) and the maerl bed at St Mawes Bank, Falmouth was estimated to have a maximum age of 4000 years (Bosence & Wilson, 2003) while carbon dating suggested that some established beds may be 4000 to 6000 years old (Birkett et al. (1998a). The maerl bed in the Sound of Iona recorded to be ˂4000 years old (Hall-Spencer et al., 2003). Maerl is considered to be a non-renewable resource due to its very slow growth rate and its inability to sustain direct exploitation (Barbera et al., 2003; Wilson et al., 2004).

Over 500,000 tonnes per annum of maerl are dredged up from the coast of Brittany. Maerl is primarily sold dried as a soil additive but is also used in animal feed, water filtration systems, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and bone surgery. Maerl is frequently washed up in some locations in Scotland and Ireland in sufficient quantities to form white 'coral' beaches.

Bibliography

Adey, W.H. & McKibbin, D.L., 1970. Studies on the maerl species Phymatolithon calcareum (Pallas) nov. comb. and Lithothamnion corallioides (Crouan) in the Ria de Vigo. Botanica Marina, 13, 100-106.

Barbera C., Bordehore C., Borg J.A., Glemarec M., Grall J., Hall-Spencer J.M., De la Huz C., Lanfranco E., Lastra M., Moore P.G., Mora J., Pita M.E., Ramos-Espla A.A., Rizzo M., Sanchez-Mata A., Seva A., Schembri P.J. and Valle C. 2003. Conservation and managment of northeast Atlantic and Mediterranean maerl beds. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 13, S65-S76.

Barbera C., Bordehore C., Borg J.A., Glemarec M., Grall J., Hall-Spencer J.M., De la Huz C., Lanfranco E., Lastra M., Moore P.G., Mora J., Pita M.E., Ramos-Espla A.A., Rizzo M., Sanchez-Mata A., Seva A., Schembri P.J. and Valle C. 2003. Conservation and managment of northeast Atlantic and Mediterranean maerl beds. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 13, S65-S76.

BIOMAERL team, 1998. Maerl grounds: Habitats of high biodiversity in European seas. In Proceedings of the Third European Marine Science and Technology Conference, Lisbon 23-27 May 1998, Project Synopses, pp. 170-178.

Birkett, D.A., Maggs, C.A. & Dring, M.J., 1998a. Maerl. an overview of dynamic and sensitivity characteristics for conservation management of marine SACs. Natura 2000 report prepared by Scottish Association of Marine Science (SAMS) for the UK Marine SACs Project., Scottish Association for Marine Science. (UK Marine SACs Project, vol V.). Available from: http://ukmpa.marinebiodiversity.org/uk_sacs/publications.htm

Blake, C. & Maggs, C.A., 2003. Comparative growth rates and internal banding periodicity of maerl species (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) from northern Europe. Phycologia, 42 (6), 606-612.

Blake, C., Maggs, C. & Reimer, P., 2007. Use of radiocarbon dating to interpret past environments of maerl beds. Ciencias Marinas, 33 (4), 385-397.

Blunden G., 1991. Agricultural uses of seaweeds and seaweed extracts. In Guiry M. D. & Blunden, G. Seaweed Resources in Europe: Uses and Potential. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, pp. 65-81

Bosence D. and Wilson J. 2003. Maerl growth, carbonate production rates and accumulation rates in the northeast Atlantic. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 13, S21-S31.

Bosence, D.W., 1976. Ecological studies on two unattached coralline algae from western Ireland. Palaeontology, 19 (2), 365-395.

Bricker, S.B., Clement, C.G., Pirhalla, D.E., Orlando, S.P. & Farrow, D.R., 1999. National estuarine eutrophication assessment: effects of nutrient enrichment in the nation's estuaries. NOAA, National Ocean Service, Special Projects Office and the National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science, Silver Spring, MD, 71 pp.

Bricker, S.B., Longstaff, B., Dennison, W., Jones, A., Boicourt, K., Wicks, C. & Woerner, J., 2008. Effects of nutrient enrichment in the nation's estuaries: a decade of change. Harmful Algae, 8 (1), 21-32.

Cabioch, J., 1969. Les fonds de maerl de la baie de Morlaix et leur peuplement vegetale. Cahiers de Biologie Marine, 10, 139-161.

Connor, D.W., Allen, J.H., Golding, N., Howell, K.L., Lieberknecht, L.M., Northen, K.O. & Reker, J.B., 2004. The Marine Habitat Classification for Britain and Ireland. Version 04.05. ISBN 1 861 07561 8. In JNCC (2015), The Marine Habitat Classification for Britain and Ireland Version 15.03. [2019-07-24]. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough. Available from https://mhc.jncc.gov.uk/

Donnan, D.W. & Davies, J., 1996. Assessing the Natural Heritage Importance of Scotland's Maerl Resource. In Partnership in Coastal Zone Management, (ed. J. Taussik & J. Mitchel), 533-540.

Dyer M. and Worsfold T. 1998. Comparative maerl surveys in Falmouth Bay. Report to English Nature from Unicomarine Ltd., Letchworth: Unicomarine Ltd

Foster, M.S., 2001. Rhodoliths: between rocks and soft places. Journal of Phycology, 37 (5), 659-667.

Grall J. & Hall-Spencer J.M. 2003. Problems facing maerl conservation in Brittany. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 13, S55-S64. DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.568

Grall J., Glémarec, M., 1997. Using biotic indices to estimate macrobenthic community perturbations in the Bay of Brest. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 44, 43–53. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7714(97)80006-6

Grall, J. & Glemarec, J., 1997. Biodiversity des fonds de maerl en Bretagne: approche fonctionelle et impacts anthropiques. Vie et Milieu, 47, 339-349.

Guiry, M.D., 1998. Phymatolithon calcareum, (Pallas) Adey and McKibbin. http://seaweed.ucg.ie/descriptions/Phycal.html, 1999-08-31

Hall-Spencer J., Kelly J. and Maggs C. 2010. Background document for Maerl Beds. OSPAR Commission, The Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government (DEHLG), Ireland

Hall-Spencer J., White N., Gillespie E., Gillham K. and Foggo A. 2006. Impact of fish farms on maerl beds in strongly tidal areas. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 326, 1-9

Hall-Spencer, J.M. & Atkinson, R.J.A., 1999. Upogebia deltaura (Crustacea: Thalassinidea) in Clyde Sea maerl beds, Scotland. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 79, 871-880.

Hall-Spencer, J.M. & Moore, P.G., 2000a. Impact of scallop dredging on maerl grounds. In Effects of fishing on non-target species and habitats. (ed. M.J. Kaiser & S.J., de Groot) 105-117. Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Hall-Spencer, J.M. & Moore, P.G., 2000b. Limaria hians (Mollusca: Limacea): A neglected reef-forming keystone species. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 10, 267-278.

Hall-Spencer, J.M. & Moore, P.G., 2000c. Scallop dredging has profound, long-term impacts on maerl habitats. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 57, 1407-1415.

Hall-Spencer, J.M., 1994. Biological studies on nongeniculate Corallinaceae. Ph.D. thesis, University of London.

Hall-Spencer, J.M., 1998. Conservation issues relating to maerl beds as habitats for molluscs. Journal of Conchology Special Publication, 2, 271-286.

Hall-Spencer, J.M., Grall, J., Moore, P.G. & Atkinson, R.J.A., 2003. Bivalve fishing and maerl-bed conservation in France and the UK - retrospect and prospect. Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems, 13, Suppl. 1 S33-S41. DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/aqc.566

Hall-Spencer, J.M., Tasker, M., Soffker, M., Christiansen, S., Rogers, S.I., Campbell, M. & Hoydal, K., 2009. Design of Marine Protected Areas on high seas and territorial waters of Rockall Bank. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 397, 305-308.

Hardy, F.G. & Guiry, M.D., 2003. A check-list and atlas of the seaweeds of Britain and Ireland. London: British Phycological Society

Howson, C.M. & Picton, B.E., 1997. The species directory of the marine fauna and flora of the British Isles and surrounding seas. Belfast: Ulster Museum. [Ulster Museum publication, no. 276.]

Irvine, L. M. & Chamberlain, Y. M., 1994. Seaweeds of the British Isles, vol. 1. Rhodophyta, Part 2B Corallinales, Hildenbrandiales. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office.

Jacquotte, R., 1962. Etude des fonds de maërl de Méditerranée. Recueil des Travaux de la Stations Marine d'Endoume, 26, 141-235.

Johnston, E.L. & Roberts, D.A., 2009. Contaminants reduce the richness and evenness of marine communities: a review and meta-analysis. Environmental Pollution, 157 (6), 1745-1752.

Joubin, L., 1910. Nemertea, National Antarctic Expedition, 1901-1904, 5: 1-15. SÁIZ-SALINAS, J.I.; RAMOS, A.; GARCÍA, F.J.; TRONCOSO, J.S.; SAN

Kamenos N.A., Moore P.G. & Hall-Spencer J.M. 2003. Substratum heterogeneity of dredged vs un-dredged maerl grounds. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the UK, 83(02), 411-413.

Keegan, B.F., 1974. The macro fauna of maerl substrates on the west coast of Ireland. Cahiers de Biologie Marine, XV, 513-530.

Littler, M.M., Littler, D.S. & Hanisak, M.D., 1991. Deep-water rhodolith distribution, productivity, and growth history at sites of formation and subsequent degradation. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 150 (2), 163-182.

Maggs, C.A. & Guiry, M.D., 1987. Gelidiella calcicola sp. nov. (Rhodophyta) from the British Isles and northern France. British Phycological Journal, 22, 417-434.

Martin, C.J., 1994. A marine survey and environmental assessment of the proposed dredging of dead maerl within Falmouth Bay by the Cornish Calcified Seaweed Company Ltd. Contractor: Environemtal Tracing Systems Ltd. pp 59.

Martin, S. & Hall-Spencer, J.M., 2017. Effects of Ocean Warming and Acidification on Rhodolith / Maerl Beds. In Riosmena-Rodriguez, R., Nelson, W., Aguirre, J. (ed.) Rhodolith / Maerl Beds: A Global Perspective, Switzerland: Springer Nature, pp. 55-85. [Coastal Research Library, 15].

Martin, S., Castets, M.-D. & Clavier, J., 2006. Primary production, respiration and calcification of the temperate free-living coralline alga Lithothamnion corallioides. Aquatic Botany, 85 (2), 121-128. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquabot.2006.02.005

Melbourne, L.A., Hernández-Kantún, J.J., Russell, S. & Brodie, J., 2017. There is more to maerl than meets the eye: DNA barcoding reveals a new species in Britain, Lithothamnion erinaceum sp. nov. (Hapalidiales, Rhodophyta). European Journal of Phycology, 52 (2), 166-178. DOI 10.1080/09670262.2016.1269953

Peña, V., Bárbara, I., Grall, J., Maggs, C.A. & Hall-Spencer, J.M., 2014. The diversity of seaweeds on maerl in the NE Atlantic. Marine Biodiversity, 44 (4), 533-551. DOI: 10.1007/s12526-014-0214-7

Potin, P., Floc'h, J.Y., Augris, C., & Cabioch, J., 1990. Annual growth rate of the calcareous red alga Lithothamnion corallioides (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) in the bay of Brest, France. Hydrobiologia, 204/205, 263-277

Tyler-Walters, H., 2013. Beds of dead maerl. Marine Life Information Network: Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Sub-programme [on-line], Plymouth: Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. [cited 12/02/16]. Available from:http://www.marlin.ac.uk/habitats/detail/999

Vadas, R.L., Johnson, S. & Norton, T.A., 1992. Recruitment and mortality of early post-settlement stages of benthic algae. British Phycological Journal, 27, 331-351.

Wilson S., Blake C., Berges J.A. & Maggs C.A., 2004. Environmental tolerances of free-living coralline algae (maerl): implications for European marine conservation. Biological Conservation, 120(2), 279-289. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2004.03.001

Datasets

Centre for Environmental Data and Recording, 2018. Ulster Museum Marine Surveys of Northern Ireland Coastal Waters. Occurrence dataset https://www.nmni.com/CEDaR/CEDaR-Centre-for-Environmental-Data-and-Recording.aspx accessed via NBNAtlas.org on 2018-09-25.

NBN (National Biodiversity Network) Atlas. Available from: https://www.nbnatlas.org.

OBIS (Ocean Biodiversity Information System), 2025. Global map of species distribution using gridded data. Available from: Ocean Biogeographic Information System. www.iobis.org. Accessed: 2025-07-30

Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, 2018. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh Herbarium (E). Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/ypoair accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-02.

Citation

This review can be cited as:

Last Updated: 30/03/2017