Sea potato (Echinocardium cordatum)

Distribution data supplied by the Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS). To interrogate UK data visit the NBN Atlas.Map Help

| Researched by | Jacqueline Hill | Refereed by | Prof. David Nichols |

| Authority | (Pennant, 1777) | ||

| Other common names | - | Synonyms | - |

Summary

Description

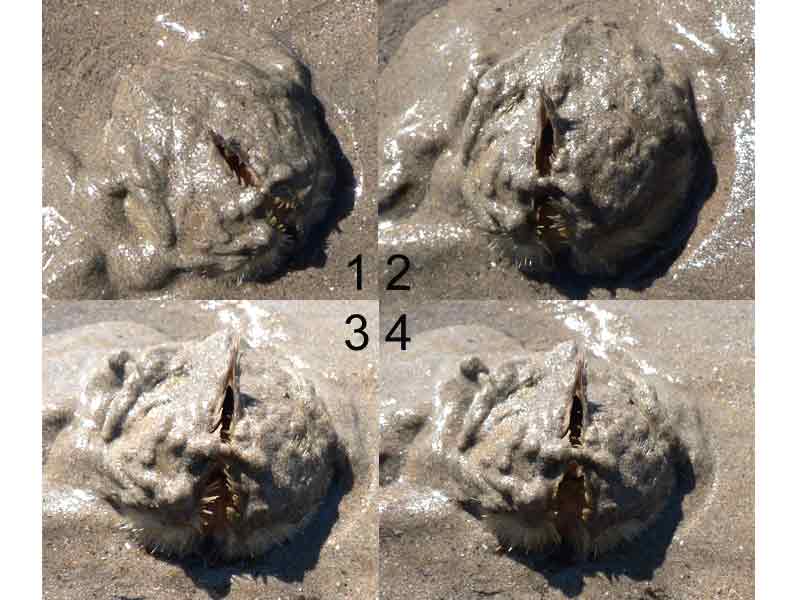

A heart shaped urchin covered in a dense felt of yellow spines, mostly directed backwards. Yellow-brown in colour and usually 6 cm in length although can grow up to 9 cm long.

Recorded distribution in Britain and Ireland

Echinocardium cordatum is a common infaunal species found on sheltered sandy beaches, on all coasts of Britain and Ireland.

Global distribution

Almost cosmopolitan except for polar seas: Norway to South Africa, Mediterranean, Australasia and Japan.

Habitat

Echinocardium cordatum lives in a permanent burrow buried about 8 cm deep (to 15 cm) in sandy sediments. The species is found from the intertidal to the subtidal and offshore to about 200 m.

Depth range

0 to -200mIdentifying features

- Heart shaped test 6-9 cm in length, fawn in colour, spines yellowish. In profile, highest point of test posterior to apical system.

- Ambulacra rather broad and furrow like, extending down the sides of test, forming a stellate shape.

- The two series of tube feet in the anterior ambulacrum each forms a double row as seen by the pore-pairs on the test.

- Some large spines and their prominent tubercles scattered ventro-laterally on the anterior interambulacra.

Additional information

The common name of this species refers to the brittle, brownish test, which is often found washed up on sheltered sandy shores.

Listed by

- none -

Biology review

Taxonomy

| Level | Scientific name | Common name |

|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Echinodermata | Starfish, brittlestars, sea urchins & sea cucumbers |

| Class | Echinoidea | Sea urchins, heart urchins and sand dollars |

| Order | Spatangoida | |

| Family | Loveniidae | |

| Genus | Echinocardium | |

| Authority | (Pennant, 1777) | |

| Recent Synonyms | ||

Biology

| Parameter | Data | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical abundance | High density | ||

| Male size range | |||

| Male size at maturity | |||

| Female size range | Small-medium (3-10 cm) | ||

| Female size at maturity | |||

| Growth form | Globose | ||

| Growth rate | 1-2cm/year | ||

| Body flexibility | None (less than 10 degrees) | ||

| Mobility | |||

| Characteristic feeding method | Sub-surface deposit feeder | ||

| Diet/food source | Detritivore | ||

| Typically feeds on | Detritus | ||

| Sociability | No information | ||

| Environmental position | Infaunal | ||

| Dependency | Independent. | ||

| Supports | See additional information | ||

| Is the species harmful? | No | ||

Biology information

- Growth in Echinocardium cordatum is particularly rapid during the first and second years of life. There are also seasonal variations that are characterised by an alternation of slow and rapid growth rates, with rapid growth during spring and summer months (Ridder de et al., 1991).

- The bivalve Tellimya ferruginosa is a commensal of Echinocardium cordatum, and as many as 14 or more of this bivalve have been recorded with a single echinoderm. Adult specimens live freely in the burrow of Echinocardium cordatum, while the young are attached to the spines of the echinoderm by byssus threads (Fish & Fish, 1996). The amphipod crustacean Urothoe marina (Bate) is another common commensal (Hayward & Ryland, 1995).

Habitat preferences

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Physiographic preferences | Enclosed coast or Embayment, Offshore seabed, Open coast, Strait or Sound |

| Biological zone preferences | Circalittoral offshore, Lower circalittoral, Lower eulittoral, Lower infralittoral, Sublittoral fringe, Upper circalittoral, Upper infralittoral |

| Substratum / habitat preferences | Coarse clean sand, Fine clean sand, Muddy sand, Sandy mud |

| Tidal strength preferences | No information |

| Wave exposure preferences | Extremely sheltered, Sheltered, Very sheltered |

| Salinity preferences | Full (30-40 psu), Reduced (18-30 psu) |

| Depth range | 0 to -200m |

| Other preferences | No text entered |

| Migration Pattern | Seasonal (reproduction) |

Habitat Information

The species has an annual tendency to form aggregations during the breeding season (Buchanan, 1966). There is also a migration of individuals from the subtidal to the intertidal at about two years of age.

Life history

Adult characteristics

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Reproductive type | Gonochoristic (dioecious) |

| Reproductive frequency | Annual episodic |

| Fecundity (number of eggs) | >1,000,000 |

| Generation time | Insufficient information |

| Age at maturity | 2-3 years |

| Season | Spring - Summer |

| Life span | 10-20 years |

Larval characteristics

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Larval/propagule type | - |

| Larval/juvenile development | Planktotrophic |

| Duration of larval stage | No information |

| Larval dispersal potential | No information |

| Larval settlement period | Insufficient information |

Life history information

Lifespan. Observation of populations of Echinocardium cordatum over a period of seven years suggests the species has a lifespan greater than 10 years (Buchanan, 1966; Hayward et al., 1996). However, in the Mediterranean Guillou (1985) suggests the lifespan is one or two years.

Age at maturity. On the north-east coast of England, a littoral population bred for the first time when three years old. In the warmer waters of the west of Scotland breeding has been recorded at the end of the second year (Fish & Fish, 1996). However, it has been observed that subtidal populations appear never to reach sexual maturity (Buchanan, 1967).

Recruitment. Often sporadic, with reports of Echinocardium cordatum recruiting in only three years over a 10-year period (Buchanan, 1966) although this relates to subtidal populations. Intertidal individuals reproduce more frequently. The sexes are separate and fertilization external, with the development of a pelagic larva (Fish & Fish, 1996). The fact that Echinocardium cordatum is to be found associated with several different bottom communities would indicate that the larvae are not highly selective and discriminatory and it is probable that the degree of discrimination in 'larval choice' becomes diminished with the age of the larvae (Buchanan, 1966). Metamorphosis of larvae takes place within 39 days after fertilization (Kashenko, 1994).

Sensitivity review

The MarLIN sensitivity assessment approach used below has been superseded by the MarESA (Marine Evidence-based Sensitivity Assessment) approach (see menu). The MarLIN approach was used for assessments from 1999-2010. The MarESA approach reflects the recent conservation imperatives and terminology and is used for sensitivity assessments from 2014 onwards.

Physical pressures

Use / to open/close text displayed

| Intolerance | Recoverability | Sensitivity | Evidence / Confidence | |

Substratum loss [Show more]Substratum lossBenchmark. All of the substratum occupied by the species or biotope under consideration is removed. A single event is assumed for sensitivity assessment. Once the activity or event has stopped (or between regular events) suitable substratum remains or is deposited. Species or community recovery assumes that the substratum within the habitat preferences of the original species or community is present. Further details EvidenceLoss of the substratum will also remove the resident population of the burrowing Echinocardium cordatum and so intolerance is high. The species has high fecundity, normally reproduces every year and has pelagic larvae so recovery should be good. Individuals can also migrate from unaffected areas. The time for re-establishment of faunal biomass after a period of anoxia related mortality in the south-eastern North Sea was 2 years (Niermann, 1997). However, Buchanan (1966) studied a North Sea subtidal population that had not recruited for several years so recovery could take longer. | High | High | Moderate | Moderate |

Smothering [Show more]SmotheringBenchmark. All of the population of a species or an area of a biotope is smothered by sediment to a depth of 5 cm above the substratum for one month. Impermeable materials, such as concrete, oil, or tar, are likely to have a greater effect. Further details. EvidenceEchinocardium cordatum lives buried in sand up to 15 cm deep so will be not sensitive to smothering by 5 cm of sediment. | Tolerant | Not relevant | Not sensitive | High |

Increase in suspended sediment [Show more]Increase in suspended sedimentBenchmark. An arbitrary short-term, acute change in background suspended sediment concentration e.g., a change of 100 mg/l for one month. The resultant light attenuation effects are addressed under turbidity, and the effects of rapid settling out of suspended sediment are addressed under smothering. Further details EvidenceEchinocardium cordatum is probably tolerant of increases in siltation. In the bay of Mevagissey for example, where fine-grained mineral waste from the china clay industry was dumped over many years, Echinocardium cordatum was present in high numbers (Probert, 1981). However, the species feeds on detritus that accumulates on the bottom and so its growth consequently relies on the regular supply of detritus (Ridder de, et al., 1991). Therefore, a decline in siltation levels may impair growth although the species is able to migrate, albeit rather slowly, to other areas. | Low | High | Low | High |

Decrease in suspended sediment [Show more]Decrease in suspended sedimentBenchmark. An arbitrary short-term, acute change in background suspended sediment concentration e.g., a change of 100 mg/l for one month. The resultant light attenuation effects are addressed under turbidity, and the effects of rapid settling out of suspended sediment are addressed under smothering. Further details Evidence | No information | |||

Desiccation [Show more]Desiccation

EvidenceEchinocardium cordatum occurs in the subtidal and the lower intertidal. In the intertidal Echinocardium cordatum is protected from desiccation because it inhabits a burrow in soft sediments to a depth of up to 15cm. Subtidal populations are not likely to be affected by desiccation. | Low | High | Low | Moderate |

Increase in emergence regime [Show more]Increase in emergence regimeBenchmark. A one hour change in the time covered or not covered by the sea for a period of one year. Further details EvidenceEchinocardium cordatum occurs in the subtidal and the lower intertidal. Subtidal populations will not be affected by emergence at the level of the benchmark. However, an increase in emergence for intertidal populations is likely to depress the height up the shore that intertidal populations can occur. During extreme low water spring tides serious predation by gulls of shallow-burrowing Echinocardium cordatum which are normally safely out of the reach of gulls (D. Nichols pers. comm.). | Low | High | Low | Moderate |

Decrease in emergence regime [Show more]Decrease in emergence regimeBenchmark. A one hour change in the time covered or not covered by the sea for a period of one year. Further details Evidence | No information | |||

Increase in water flow rate [Show more]Increase in water flow rateA change of two categories in water flow rate (view glossary) for 1 year, for example, from moderately strong (1-3 knots) to very weak (negligible). Further details EvidenceSpatangoid echinoderms such as Echinocardium cordatum can be washed out by water currents generated by gales (Lawrence, 1989). Therefore, the species is likely to be intolerant of increases in water flow rates that similarly wash out sediments and intolerance is assessed as intermediate. | Intermediate | High | Low | Moderate |

Decrease in water flow rate [Show more]Decrease in water flow rateA change of two categories in water flow rate (view glossary) for 1 year, for example, from moderately strong (1-3 knots) to very weak (negligible). Further details Evidence | No information | |||

Increase in temperature [Show more]Increase in temperature

For intertidal species or communities, the range of temperatures includes the air temperature regime for that species or community. Further details EvidenceEchinocardium cordatum has a relatively wide degree of tolerance to temperature (Higgins, 1974) in accordance with its cosmopolitan distribution. Growth rates are generally higher growth rates in warmer waters (Duineveld & Jenness, 1984). Temperature may also be a factor fine tuning the seasonal pattern of growth where somatic growth (summer) alternates with gonadial growth (winter) (D. Nichols pers. comm.) Very low water temperature can cause mass mortalities of Echinocardium cordatum and so intolerance has been assessed as intermediate. During the severe winter of 1963 the species was almost completely eliminated from the German Bight to a depth of about 20m (Lawrence, 1996) and very heavy mortality was observed in the English Channel and North Sea (Crisp (ed.), 1964). High temperatures can also cause a suffocation effect: there can be mass mortality of Echinocardium cordatum on sandy shores following oxygen depletion during extreme low water tides on hot days (D. Nichols pers. comm.). | Intermediate | High | Low | Moderate |

Decrease in temperature [Show more]Decrease in temperature

For intertidal species or communities, the range of temperatures includes the air temperature regime for that species or community. Further details Evidence | No information | |||

Increase in turbidity [Show more]Increase in turbidity

EvidenceEchinocardium cordatum lives buried in sand up to 15 cm deep so is not likely to be affected by changes in turbidity. However, a decrease in turbidity may result in a decline in the supply of organic matter to the seabed surface from which the species feeds possibly causing reduced growth and fecundity. | Low | High | Low | Moderate |

Decrease in turbidity [Show more]Decrease in turbidity

Evidence | No information | |||

Increase in wave exposure [Show more]Increase in wave exposureA change of two ranks on the wave exposure scale (view glossary) e.g., from Exposed to Extremely exposed for a period of one year. Further details EvidenceEchinocardium cordatum is typically a sheltered shore species although in coastal waters of the Netherlands the species occurs in the tidal zone on some sandflats exposed to wave-action, at the entrances of the Oosterschelde and the Westerschelde (Wolff, 1968). In the bay of Douarnenez, Brittany Echinocardium cordatum was found only in areas of fine sand dominated by high sediment instability, due to marked exposure to westerly swells (Guillou, 1985). However, Echinocardium cordatum is unlikely to survive in areas of extreme wave exposure so intolerance is assessed as intermediate. | Intermediate | High | Low | Low |

Decrease in wave exposure [Show more]Decrease in wave exposureA change of two ranks on the wave exposure scale (view glossary) e.g., from Exposed to Extremely exposed for a period of one year. Further details Evidence | No information | |||

Noise [Show more]Noise

EvidenceNo evidence of sound or vibration reception in echinoids was found. | Tolerant | Not relevant | Not sensitive | Not relevant |

Visual presence [Show more]Visual presenceBenchmark. The continuous presence for one month of moving objects not naturally found in the marine environment (e.g., boats, machinery, and humans) within the visual envelope of the species or community under consideration. Further details EvidenceSome response to visual disturbance has been detected in echinoderms. There is some evidence that the basiepithelial nerve plexus below the entire outer skins is sensitive to light (D. Nichols pers. comm.). However, Echinocardium cordatum generally lives buried in sand up to 15cm deep and so visual disturbance is not relevant. When on the surface of the substratum visual disturbance may cause the urchin to re-burrow into the substratum. | Not relevant | Not relevant | Not relevant | Not relevant |

Abrasion & physical disturbance [Show more]Abrasion & physical disturbanceBenchmark. Force equivalent to a standard scallop dredge landing on or being dragged across the organism. A single event is assumed for assessment. This factor includes mechanical interference, crushing, physical blows against, or rubbing and erosion of the organism or habitat of interest. Where trampling is relevant, the evidence and trampling intensity will be reported in the rationale. Further details. EvidenceThe species has a fragile test that is likely to be damaged by an abrasive force such as movement of trawling gear over the seabed. A substantial reduction in the numbers of Echinocardium cordatum due to physical damage from scallop dredging has been observed (Eleftheriou & Robertson, 1992). Smaller size classes of the heart urchin are found near the surface of the sediment and are therefore likely to be more vulnerable to physical damage (Jennings & Kaiser, 1998). Echinocardium cordatum was also reported to suffer between 10 and 40% mortality due to fishing gear, depending on the type of gear and sediment after a single trawl event (Bergman & van Santbrink, 2000). They suggested that mortality may increase to 90% in summer when individuals migrate to the surface of the sediment during their short reproductive season. Bergman & van Santbrink (2000) suggested that Echinocardium cordatum was one of the most vulnerable species to trawling. Therefore, an intolerance of high has been recorded.The species has high fecundity, normally reproduces every year and has pelagic larvae so recovery should be good. The time for re-establishment of faunal biomass after a period of anoxia, for example, related mortality in the south-eastern North Sea was two years (Niermann, 1997) | High | High | Moderate | High |

Displacement [Show more]DisplacementBenchmark. Removal of the organism from the substratum and displacement from its original position onto a suitable substratum. A single event is assumed for assessment. Further details EvidenceIn the intertidal displacement from the sediment is likely to expose Echinocardium cordatum to an increased risk of predation. However, once on the substratum surface Echinocardium cordatum is capable of re-burrowing into the sediment within 20 minutes and so intolerance is low. Recovery is good because the species has a pelagic larva and individuals can migrate from unaffected areas. | Low | High | Low | Moderate |

Chemical pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Intolerance | Recoverability | Sensitivity | Evidence / Confidence | |

Synthetic compound contamination [Show more]Synthetic compound contaminationSensitivity is assessed against the available evidence for the effects of contaminants on the species (or closely related species at low confidence) or community of interest. For example:

The evidence used is stated in the rationale. Where the assessment can be based on a known activity then this is stated. The tolerance to contaminants of species of interest will be included in the rationale when available; together with relevant supporting material. Further details. EvidenceDetergents used to disperse oil from the Torrey Canyon oil spill caused mass mortalities of Echinocardium cordatum (Smith, 1968). The toxicity of TBT to Echinocardium cordatum is similar to that of other benthic organisms with LC50 values of 222ng Sn/l in pore water and 1594ng Sn/g dry weight of sediment (Stronkhorst et al., 1999). Sea-urchins, especially the eggs and larvae, are used for toxicity testing and environmental monitoring (reviewed by Dinnel et al. 1988). It is likely therefore, that Echinocardium cordatum and especially its larvae are highly sensitive to synthetic contaminants. | High | High | Moderate | Moderate |

Heavy metal contamination [Show more]Heavy metal contaminationEvidenceInformation about the effects of heavy metals on echinoderms is limited and no details specific to Echinocardium cordatum were found. However, Bryan (1984) reports that early work has shown that echinoderm larvae are intolerant of heavy metals, e.g. the intolerance of larvae of Paracentrotus lividus to copper (Cu) had been used to develop a water quality assessment. Kinne (1984) reported developmental disturbances in Echinus esculentus exposed to waters containing 25 µg / l of copper (Cu). Therefore, it is likely that Echinocardium cordatum is intolerant of heavy metal contamination and intolerance is assessed as high. | Intermediate | High | Low | Moderate |

Hydrocarbon contamination [Show more]Hydrocarbon contaminationEvidenceEchinoderms seem especially intolerant of the toxic effects of oil, likely because of the large amount of exposed epidermis (Suchanek, 1993). The high intolerance of Echinocardium cordatum to hydrocarbons was seen by the mass mortality of animals, down to about 20m, shortly after the Amoco Cadiz oil spill (Cabioch et al., 1978). Reduced abundance of the species was also detectable up to > 1000m away one year after the discharge of oil-contaminated drill cuttings in the North Sea (Daan & Mulder, 1996). The species has high fecundity, normally reproduces every year and has a pelagic larva so recovery should be good. Individuals can also migrate from unaffected areas. The first repopulation of Echinocardium cordatum after the Torrey Canyon accident was noticed two years after the oil spill (Southward & Southward, 1978). | High | High | Moderate | High |

Radionuclide contamination [Show more]Radionuclide contaminationEvidenceInsufficientinformation. | No information | No information | No information | Not relevant |

Changes in nutrient levels [Show more]Changes in nutrient levelsEvidenceEchinocardium cordatum is generally found in sediments with low organic content and the species appears to be intolerant of increases in nutrient concentration. Growth levels have been observed to be lower in sediments with high organic content although it is suggested that this may be due to higher levels of intraspecific competition (Duineveld and Jenness, 1984). The species was also absent from an area in the southern North Sea into which large quantities of sewage sludge from Hamburg had been dumped and the species was never seen to settle in the area (Caspers, 1980). Pearson & Rosenberg (1976) describe the changes in fauna along a gradient of increasing organic enrichment by pulp fibre where Echinocardium cordatum is absent from all but distant sediments with low organic input and so intolerance is assessed as high. | High | High | Moderate | High |

Increase in salinity [Show more]Increase in salinity

EvidenceEchinoderms are considered to be stenohaline animals that lack the ability to osmo- and ion-regulate (Stickle & Diehl, 1987). However, Echinocardium cordatum has been recorded from brackish waters in the Delta region of the Netherlands to about the 15psu isohaline (Wolff, 1968). Echinoderm larvae have a narrow range of salinity tolerance and will develop abnormally and die if exposed to reduced or increased salinity. | Intermediate | High | Low | Moderate |

Decrease in salinity [Show more]Decrease in salinity

Evidence | No information | |||

Changes in oxygenation [Show more]Changes in oxygenationBenchmark. Exposure to a dissolved oxygen concentration of 2 mg/l for one week. Further details. EvidenceEchinocardium cordatum is highly intolerant of reductions in oxygen concentration. Buchanan (1966) found that individuals of Echinocardium cordatum at Newton Haven burrowed into sand to a depth of 15cm but avoided penetrating into dark sand with presumably reducing conditions. In the south-eastern North Sea a period of reduced oxygen resulted in the death of many individuals of Echinocardium cordatum (Niermann, 1997) and during periods of hypoxia the species migrates to the surface of the sediment (Diaz & Rosenberg, 1995). High intolerance has also been demonstrated in laboratory experiments. At 4mg/l individuals appeared on the sediment surface and many were dead at a concentration of 2.4mg/l (Nilsson & Rosenberg, 1994). The species has high fecundity, normally reproduces every year and has a pelagic larva so recovery should be good. Individuals can also migrate from unaffected areas. The time for re-establishment of faunal biomass after a period of anoxia related mortality in the south-eastern North Sea was 2 years (Niermann, 1997). | High | High | Moderate | High |

Biological pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Intolerance | Recoverability | Sensitivity | Evidence / Confidence | |

Introduction of microbial pathogens/parasites [Show more]Introduction of microbial pathogens/parasitesBenchmark. Sensitivity can only be assessed relative to a known, named disease, likely to cause partial loss of a species population or community. Further details. EvidenceThe occurrence of several parasitic gregarine protozoans, such as Urospora neapolitana, have been observed in the body cavity of Echinocardium cordatum (Coulon & Jangoux, 1987). However, no information concerning infestation or disease related mortalities was found. | Low | High | Low | Low |

Introduction of non-native species [Show more]Introduction of non-native speciesSensitivity assessed against the likely effect of the introduction of alien or non-native species in Britain or Ireland. Further details. EvidenceNo alien or non-native species is known to compete with Echinocardium cordatum. | Not relevant | Not relevant | Not relevant | Low |

Extraction of this species [Show more]Extraction of this speciesBenchmark. Extraction removes 50% of the species or community from the area under consideration. Sensitivity will be assessed as 'intermediate'. The habitat remains intact or recovers rapidly. Any effects of the extraction process on the habitat itself are addressed under other factors, e.g. displacement, abrasion and physical disturbance, and substratum loss. Further details. EvidenceTargeted extraction of Echinocardium cordatum is unlikely although dredging may remove populations in some habitats. Recovery from dredging should be good because the species has a pelagic larva and individuals can migrate from unaffected areas. | Intermediate | High | Low | Not relevant |

Extraction of other species [Show more]Extraction of other speciesBenchmark. A species that is a required host or prey for the species under consideration (and assuming that no alternative host exists) or a keystone species in a biotope is removed. Any effects of the extraction process on the habitat itself are addressed under other factors, e.g. displacement, abrasion and physical disturbance, and substratum loss. Further details. EvidenceHydraulic dredging for razor shells (Ensis spp.) may also disturb and damage Echinocardium cordatum which is often found in the same habitat. Recovery should be good because the species has a relatively long lived pelagic larvae and individuals can migrate from unaffected areas. | Intermediate | High | Low | High |

Additional information

Importance review

Policy/legislation

- no data -

Status

| National (GB) importance | - | Global red list (IUCN) category | - |

Non-native

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Native | - |

| Origin | - |

| Date Arrived | - |

Importance information

-none-Bibliography

Bergman, M.J.N. & Van Santbrink, J.W., 2000b. Fishing mortality of populations of megafauna in sandy sediments. In The effects of fishing on non-target species and habitats (ed. M.J. Kaiser & S.J de Groot), 49-68. Oxford: Blackwell Science.

Bryan, G.W., 1984. Pollution due to heavy metals and their compounds. In Marine Ecology: A Comprehensive, Integrated Treatise on Life in the Oceans and Coastal Waters, vol. 5. Ocean Management, part 3, (ed. O. Kinne), pp.1289-1431. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Buchanan, J.B., 1966. The biology of Echinocardium cordatum (Echinodermata: Spatangoidea) from different habitats. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 46, 97-114.

Buchanan, J.B., 1967. Dispersion and demography of some infaunal echinoderm populations. Symposia of the Zoological Society of London, 20, 1-11.

Cabioch, L., Dauvin, J.C. & Gentil, F., 1978. Preliminary observations on pollution of the sea bed and disturbance of sub-littoral communities in northern Brittany by oil from the Amoco Cadiz. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 9, 303-307.

Caspers, H., 1980. Adaptation and biocoenotic associations of echinoderms in a sewage dumping area of the southern North Sea. A macro-scale experiment. In Echinoderms: present and past (ed. M. Jangoux), pp. 189-198. Rotterdam: Balkema.

Coulon, P. & Jangoux, M., 1987. Gregarine species (Apicomplexa) parasitic in the burrowing echinoid Echinocardium cordatum: occurrence and host reaction. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms, 2, 135-145.

Crisp, D.J. (ed.), 1964. The effects of the severe winter of 1962-63 on marine life in Britain. Journal of Animal Ecology, 33, 165-210.

Daan, R. & Mulder, M., 1996. On the short-term and long-term impact of drilling activities in the Dutch sector of the North Sea ICES Journal of Marine Science, 53, 1036-1044.

Diaz, R.J. & Rosenberg, R., 1995. Marine benthic hypoxia: a review of its ecological effects and the behavioural responses of benthic macrofauna. Oceanography and Marine Biology: an Annual Review, 33, 245-303.

Dinnel, P.A., Pagano, G.G., & Oshido, P.S., 1988. A sea urchin test system for marine environmental monitoring. In Echinoderm Biology. Proceedings of the Sixth International Echinoderm Conference, Victoria, 23-28 August 1987, (R.D. Burke, P.V. Mladenov, P. Lambert, Parsley, R.L. ed.), pp 611-619. Rotterdam: A.A. Balkema.

Duineveld, G.C.A. & Jenness, M.I., 1984. Differences in growth rates of the sea urchin Echinocardium cordatum as estimated by the parameters of the von Bertalanffy equation applied to skeletal rings. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 19, 64-72.

Eleftheriou, A. & Robertson, M.R., 1992. The effects of experimental scallop dredging on the fauna and physical environment of a shallow sandy community. Netherlands Journal of Sea Research, 30, 289-299.

Fish, J.D. & Fish, S., 1996. A student's guide to the seashore. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Guillou, J., 1985. Population dynamics of Echinocardium cordatum (Pennant) in the bay of Douarnenez (Brittany). In Proceedings of the Fifth International Echinocardium Conference / Galway / 24-29 September 1984 (ed. B.F. Keegan & B.D.S. O'Conner), 275-280. Rotterdam: Balkema.

Hayward, P., Nelson-Smith, T. & Shields, C. 1996. Collins pocket guide. Sea shore of Britain and northern Europe. London: HarperCollins.

Hayward, P.J. & Ryland, J.S. (ed.) 1995b. Handbook of the marine fauna of North-West Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Higgins, H.C., 1974. Specific status of Echinocardium cordatum, E. australe and E. zealandium (Echinoidea: Spatangoida) around New Zealand, with comments on the relation of morphological variation to environment. Journal of Zoology, 173, 451-475.

Jennings, S. & Kaiser, M.J., 1998. The effects of fishing on marine ecosystems. Advances in Marine Biology, 34, 201-352.

Kashenko, S.D., 1994. Larval development of the heart urchin Echinocardium cordatum feeding on different macroalgae. Biologiya Morya, 20, 385-389.

Kinne, O. (ed.), 1984. Marine Ecology: A Comprehensive, Integrated Treatise on Life in Oceans and Coastal Waters.Vol. V. Ocean Management Part 3: Pollution and Protection of the Seas - Radioactive Materials, Heavy Metals and Oil. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

Lawrence, J.M., 1996. Mass mortality of echinoderms from abiotic factors. In Echinoderm Studies Vol. 5 (ed. M. Jangoux & J.M. Lawrence), pp. 103-137. Rotterdam: A.A. Balkema.

Mortensen, T.H., 1927. Handbook of the echinoderms of the British Isles. London: Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press.

Nichols, D., 1969. Echinoderms (4th ed.). London: Hutchinson & Co.

Niermann, U., 1997. Macrobenthos of the south-eastern North Sea during 1983-1988. Berichte der Biologischen Anstalt Helgoland, 13, 144pp.

Nilsson, H.C. & Rosenberg, R., 1994. Hypoxic response of two marine benthic communities. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 115, 209-217. DOI https://doi.org/10.3354/meps115209

Pearson, T.H. & Rosenberg, R., 1976. A comparative study of the effects on the marine environment of wastes from cellulose industries in Scotland and Sweden. Ambio, 5, 77-79.

Probert, P.K., 1981. Changes in the benthic community of china clay waste deposits is Mevagissey Bay following a reduction of discharges. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 61, 789-804. Doi https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315400048219

Ridder de, C., David, B., Laurin, B. & Gall le, P., 1991. Population dynamics of the spatangoid echinoid Echinocardium cordatum (Pennant) in the Bay of Seine, Normandy. In Proceedings of the Seventh International Echinoderm Conference Atami, 9 - 14 September 1991: Biology of Echinodermata, (ed. Yanagisawa, T., Yasumasu, I., Oguro, C., Suzuki, N. & Motokawa, T.), 153-158. Balkema, Rotterdam.

Rumohr, H. & Kujawski, T., 2000. The impact of trawl fishery on the epifauna of the southern North Sea. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 57, 1389-1394.

Smith, J.E. (ed.), 1968. 'Torrey Canyon'. Pollution and marine life. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Southward, A.J. & Southward, E.C., 1978. Recolonisation of rocky shores in Cornwall after use of toxic dispersants to clean up the Torrey Canyon spill. Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, 35, 682-706.

Stickle, W.B. & Diehl, W.J., 1987. Effects of salinity on echinoderms. In Echinoderm Studies, Vol. 2 (ed. M. Jangoux & J.M. Lawrence), pp. 235-285. A.A. Balkema: Rotterdam.

Stronkhorst, J., Hattum van, B. & Bowmer, T., 1999. Bioaccumulation and toxicity of tributyltin to a burrowing heart urchin and an amphipod in spiked, silty marine sediments. Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 18 (10), 2343-2351. DOI https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620181031

Suchanek, T.H., 1993. Oil impacts on marine invertebrate populations and communities. American Zoologist, 33, 510-523. DOI https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/33.6.510

Wolff, W.J., 1968. The Echinodermata of the estuarine region of the rivers Rhine, Meuse and Scheldt, with a list of species occurring in the coastal waters of the Netherlands. The Netherlands Journal of Sea Research, 4, 59-85.

Datasets

Centre for Environmental Data and Recording, 2018. Ulster Museum Marine Surveys of Northern Ireland Coastal Waters. Occurrence dataset https://www.nmni.com/CEDaR/CEDaR-Centre-for-Environmental-Data-and-Recording.aspx accessed via NBNAtlas.org on 2018-09-25.

Cofnod – North Wales Environmental Information Service, 2018. Miscellaneous records held on the Cofnod database. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/hcgqsi accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-09-25.

Environmental Records Information Centre North East, 2018. ERIC NE Combined dataset to 2017. Occurrence dataset: http://www.ericnortheast.org.ukl accessed via NBNAtlas.org on 2018-09-38

Fenwick, 2018. Aphotomarine. Occurrence dataset http://www.aphotomarine.com/index.html Accessed via NBNAtlas.org on 2018-10-01

Fife Nature Records Centre, 2018. St Andrews BioBlitz 2015. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/xtrbvy accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-09-27.

Isle of Wight Local Records Centre, 2017. IOW Natural History & Archaeological Society Marine Invertebrate Records 1853- 2011. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/d9amhg accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-09-27.

Kent Wildlife Trust, 2018. Kent Wildlife Trust Shoresearch Intertidal Survey 2004 onwards. Occurrence dataset: https://www.kentwildlifetrust.org.uk/ accessed via NBNAtlas.org on 2018-10-01.

Lancashire Environment Record Network, 2018. LERN Records. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/esxc9a accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

Manx Biological Recording Partnership, 2017. Isle of Man wildlife records from 01/01/2000 to 13/02/2017. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/mopwow accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

Manx Biological Recording Partnership, 2018. Isle of Man historical wildlife records 1995 to 1999. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/lo2tge accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

Merseyside BioBank., 2018. Merseyside BioBank (unverified). Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/iou2ld accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

National Trust, 2017. National Trust Species Records. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/opc6g1 accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

NBN (National Biodiversity Network) Atlas. Available from: https://www.nbnatlas.org.

OBIS (Ocean Biodiversity Information System), 2025. Global map of species distribution using gridded data. Available from: Ocean Biogeographic Information System. www.iobis.org. Accessed: 2025-05-21

Outer Hebrides Biological Recording, 2018. Invertebrates (except insects), Outer Hebrides. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/hpavud accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

South East Wales Biodiversity Records Centre, 2023. SEWBReC Marine and other Aquatic Invertebrates (South East Wales). Occurrence dataset:https://doi.org/10.15468/zxy1n6 accessed via GBIF.org on 2024-09-27.

Citation

This review can be cited as:

Last Updated: 13/05/2008