Bladder wrack (Fucus vesiculosus)

Distribution data supplied by the Ocean Biodiversity Information System (OBIS). To interrogate UK data visit the NBN Atlas.Map Help

| Researched by | Nicola White | Refereed by | Dr Stefan Kraan |

| Authority | Linnaeus, 1753 | ||

| Other common names | - | Synonyms | - |

Summary

Description

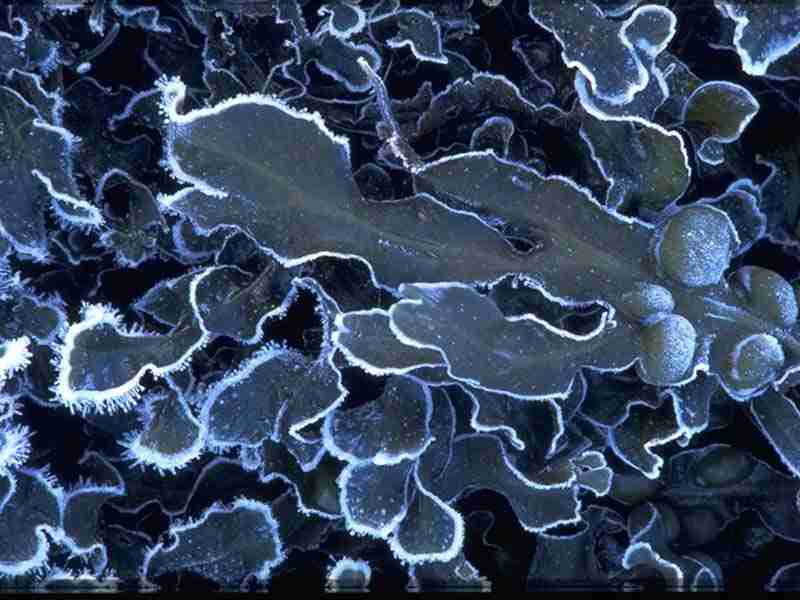

The bladder wrack Fucus vesiculosus is a large brown algae, common on the middle shore. It can be found in high densities living for about 4-5 years (S. Kraan, pers. comm.). Under sheltered conditions, the fronds have been known to grow up to 2 m in Maine, America (Wippelhauser, 1996).

Recorded distribution in Britain and Ireland

All coasts of Britain and Ireland.

Global distribution

Fucus vesiculosus is found in the Baltic Sea, Faroes, Norway (including Spitsbergen), Sweden, Britain, Ireland, the Atlantic coast of France, Spain and Morocco, Madeira, the Azores, Portugal, the North Sea coast of Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium and the eastern shores of the United States and Canada.

Habitat

The species is found intertidally on rocky shores in a wide range of exposures. It is common on the mid shore often with Ascophyllum nodosum, below Fucus spiralis and in a zone further up the shore from Fucus serratus.

Depth range

Not relevantIdentifying features

- Frond with prominent midrib and almost spherical air bladders.

- Air bladders usually paired but may be absent in very small plants.

- Margin of frond smooth.

- Dichotomously branched.

- The species may be confused with Fucus spiralis with which it hybridizes.

- A bladderless form occurs on more wave exposed shores (S. Kraan, pers. comm.).

Additional information

-none-Listed by

- none -

Biology review

Taxonomy

| Level | Scientific name | Common name |

|---|---|---|

| Phylum | Ochrophyta | Brown and yellow-green seaweeds |

| Class | Phaeophyceae | |

| Order | Fucales | |

| Family | Fucaceae | |

| Genus | Fucus | |

| Authority | Linnaeus, 1753 | |

| Recent Synonyms | ||

Biology

| Parameter | Data | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical abundance | High density | ||

| Male size range | Up to 1.5 m | ||

| Male size at maturity | 15-20 cm | ||

| Female size range | 15-20 cm | ||

| Female size at maturity | |||

| Growth form | Foliose | ||

| Growth rate | 0.48cm/week | ||

| Body flexibility | |||

| Mobility | Sessile, permanent attachment | ||

| Characteristic feeding method | Autotroph | ||

| Diet/food source | Autotroph | ||

| Typically feeds on | |||

| Sociability | Not relevant | ||

| Environmental position | Epifloral | ||

| Dependency | Independent. | ||

| Supports | None | ||

| Is the species harmful? | No | ||

Biology information

Air bladders or vesicles are produced annually to make the frond float upwards when immersed, except at highly exposed coasts where no air bladders are produced (S. Kraan, pers. comm.). Fucus vesiculosus supports few colonial organisms but provides substratum and shelter for the tube worm Spirorbis spirorbis, herbivorous isopods, such as Idotea, and surface grazing snails, such as Littorina obtusata.

The growth rate of fucoids is known to vary both geographically and seasonally (Lehvo et al., 2001). Relative growth rate can vary from 0.05-0.14 cm/day depending on temperature and light conditions (S. Kraan, pers. comm.). The increase in growth rate for Fucus vesiculosus at 10, 12.5 and 15°C was found to be, on average, 280% higher than it was at 7°C (Strömgren, 1977). In the northern Baltic, the highest relative growth rate of vegetative branches for Fucus vesiculosus was observed in the summer (up to 0.7% / day ) compared to winter growth (less than 0.3% / day). In Sweden, growth rates of 0.7-0.8 cm/week were reported over the summer months of June and August (Carlson, 1991).

The growth rate can also vary with exposure. In Scotland, Fucus vesiculosus at Sgeir Bhuidhe, a very exposed site, grew about 0.31 cm/week whereas plants at Ascophyllum Rock grew an average of 0.68 cm/week (Knight & Parke, 1950). The proportion of energy allocated between vegetative and reproductive growth also varies throughout the year. In the northern Baltic, reproductive branches experienced a peak in growth rate in mid-April where the relative growth rate was almost 0.1% / day (Lehvo et al., 2001).

Habitat preferences

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Physiographic preferences | Enclosed coast or Embayment, Estuary, Open coast, Ria or Voe, Sea loch or Sea lough, Strait or Sound |

| Biological zone preferences | Mid eulittoral, Upper eulittoral |

| Substratum / habitat preferences | Artificial (man-made), Bedrock, Cobbles, Gravel / shingle, Large to very large boulders, Pebbles, Small boulders |

| Tidal strength preferences | Moderately strong 1 to 3 knots (0.5-1.5 m/sec.), Strong 3 to 6 knots (1.5-3 m/sec.), Very weak (negligible), Weak < 1 knot (<0.5 m/sec.) |

| Wave exposure preferences | Moderately exposed, Sheltered, Very sheltered |

| Salinity preferences | Full (30-40 psu), Reduced (18-30 psu), Variable (18-40 psu) |

| Depth range | Not relevant |

| Other preferences | No text entered |

| Migration Pattern | Non-migratory or resident |

Habitat Information

The morphology of the plant varies in response to the environmental conditions leading to distinct varieties. Also, the fact that it can hybridize freely with other fucoids leads to the formation of distinct varieties (S. Kraan, pers. comm.). This species can survive in exposed locations, even though it is not a preferred habitat, but survive as a dwarf form (S. Kraan, pers. comm.). Plants from exposed locations usually have no air bladders and are known as Fucus vesiculosus forma evesiculosus (formally Fucus vesiculosus forma linearis) which may be mistaken for Fucus ceranoides. The loss of air bladders is thought to be because they increase a plant's drag, making them more vulnerable to being washed off by waves. Depth is not relevant as the plant is intertidal although it does occur at shallow depths in the Baltic.

Life history

Adult characteristics

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Reproductive type | Gonochoristic (dioecious) |

| Reproductive frequency | Annual episodic |

| Fecundity (number of eggs) | >1,000,000 |

| Generation time | 1-2 years |

| Age at maturity | Insufficient information |

| Season | Winter - Summer |

| Life span | 2-5 years |

Larval characteristics

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Larval/propagule type | - |

| Larval/juvenile development | Not relevant |

| Duration of larval stage | No information |

| Larval dispersal potential | No information |

| Larval settlement period | Insufficient information |

Life history information

The species is highly fecund often bearing more than 1000 receptacles on each plant, which may produce in excess of one million eggs. Development of the receptacles takes three months from initiation until gametes are released. On British shores, receptacles are initiated around December and may be present on the plant till late summer. In Sweden, receptacles were reportedly present from February through to October (Carlson, 1991).

In England, the species has a protracted reproduction period of about six months which varies only slightly in timing between a population at Wembury on the south coast of Devon and one at Port Erin, Isle of Man (Knight & Parke, 1950). Gametes may be produced from mid-winter until late summer with a peak of fertility in May and June. According to Berger et al. (2001), Fucus vesiculosus reproduced in either of two periods in the Baltic, the first period being early summer (May to June) and the second being late autumn (September to November).

Plants are dioecious. Gametes are generally released into the seawater under calm conditions (Mann, 1972; Serrão et al., 2000) and the eggs are fertilized externally to produce a zygote. In the Baltic, summer spawning plants produced smaller but more eggs than plants reproducing in late autumn (September - November): egg production was approximately 210,000 eggs/gram frond mass with an egg size of 0.067 mm and 89,000 egg/gram frond mass with an egg size of 0.07 mm for summer and autumn periods respectively (Berger et al, 2001). Both periods experienced similar recruitment success. Eggs are fertilized shortly after being released from the receptacle. On the coast of Maine, sampling on three separate occasions during the reproductive season revealed 100% fertilization on both exposed and sheltered shores (Serrão et al., 2000). Fertilization is not considered as a limiting factor in reproduction in this species (Mann, 1972; Serrã0 et al., 2000). Zygotes start to develop whenever they settle, even if the substratum is entirely unsuitable. The egg adheres to the rock within hours of settlement and the germling may be visible to the naked eye within a couple of weeks (Knight & Parke, 1950). The zygote is sticky (S. Kraan, pers. comm.) and may adhere firmly enough to resist removal by the next returning tide (Knight & Parke, 1950). Mortality is extremely high in the early stages of germination up to a time when plants are 3 cm in length and this is due mostly to mollusc predation (Knight & Parke 1950). In the Baltic, for example, a total of more than 1000 fertilized eggs per cm² were observed on the sea floor around the females over the two-month reproductive season (Serrão et al., 2000). By the end of the season, however, the number of germlings growing in the same area was at least an order of magnitude lower.

The timing of reproduction in this species can, to a certain extent, be influenced by wave exposure and reproduction is sometimes initiated earlier in sheltered conditions (Knight & Parke, 1950). In Finland, the amount of energy proportioned to reproduction was significantly higher on exposed sites than in sheltered localities (Bäck et al, 1991).

Sensitivity review

The MarLIN sensitivity assessment approach used below has been superseded by the MarESA (Marine Evidence-based Sensitivity Assessment) approach (see menu). The MarLIN approach was used for assessments from 1999-2010. The MarESA approach reflects the recent conservation imperatives and terminology and is used for sensitivity assessments from 2014 onwards.

Physical pressures

Use / to open/close text displayed

| Intolerance | Recoverability | Sensitivity | Evidence / Confidence | |

Substratum loss [Show more]Substratum lossBenchmark. All of the substratum occupied by the species or biotope under consideration is removed. A single event is assumed for sensitivity assessment. Once the activity or event has stopped (or between regular events) suitable substratum remains or is deposited. Species or community recovery assumes that the substratum within the habitat preferences of the original species or community is present. Further details EvidenceFucus vesiculosus attaches permanently to the substratum, and would therefore be removed upon substratum loss. However, this factor is not thought to lead to the mass mortality of the population (S. Kraan, pers. comm.) and therefore intolerance has been assessed as intermediate. Recovery would be high due to the high fecundity of the species and it's widespread distribution. Fucus vesiculosus recruits readily to cleared areas of the shore and full recovery takes 1-3 years (Holt et al., 1997). | Intermediate | High | Low | Moderate |

Smothering [Show more]SmotheringBenchmark. All of the population of a species or an area of a biotope is smothered by sediment to a depth of 5 cm above the substratum for one month. Impermeable materials, such as concrete, oil, or tar, are likely to have a greater effect. Further details. EvidenceIf smothering occurs while the tide is out all surfaces of the plant will be covered in sediment, preventing photosynthesis. If smothering occurs while the plant is immersed fewer surfaces will be covered, allowing photosynthesis to continue. Germlings will be smothered and die. Recovery should be high due to the high fecundity of the species and it's widespread distribution. Fucus vesiculosus recruits readily to cleared areas of the shore and full recovery takes 1-3 years. | High | High | Moderate | Low |

Increase in suspended sediment [Show more]Increase in suspended sedimentBenchmark. An arbitrary short-term, acute change in background suspended sediment concentration e.g., a change of 100 mg/l for one month. The resultant light attenuation effects are addressed under turbidity, and the effects of rapid settling out of suspended sediment are addressed under smothering. Further details EvidenceSiltation may cover some of the fronds and so reduce light available for photosynthesis and lower growth rates. Once silt is removed the growth rate should rapidly recover. | Low | Immediate | Not sensitive | Low |

Decrease in suspended sediment [Show more]Decrease in suspended sedimentBenchmark. An arbitrary short-term, acute change in background suspended sediment concentration e.g., a change of 100 mg/l for one month. The resultant light attenuation effects are addressed under turbidity, and the effects of rapid settling out of suspended sediment are addressed under smothering. Further details Evidence | No information | |||

Desiccation [Show more]Desiccation

EvidenceFucus vesiculosus can tolerate desiccation until the water content is reduced to 30%. If desiccation occurs beyond this level, irreversible damage occurs. The plants at the top of the range probably live at the upper limit of their physiological tolerance and therefore are likely to be unable to tolerate increased desiccation and would be displaced by more physiologically tolerant species. However, individuals at the lower limit of the species distributional range would probably survive so intolerance is reported to be intermediate. Decreased levels of desiccation may result in the species colonizing further up the shore. Recovery would be rapid due to the high fecundity of the species, its widespread distribution and capacity for dispersal.Fucus vesiculosus recruits readily to cleared areas of the shore although full recovery may take 1-3 years. | Intermediate | High | Low | Moderate |

Increase in emergence regime [Show more]Increase in emergence regimeBenchmark. A one hour change in the time covered or not covered by the sea for a period of one year. Further details EvidenceThe primary effect of emersion upon algae would be desiccation. Emersion for just 4 hours on a sunny day can reduce the water content of Fucus vesiculosus to just 30 percent. This is the critical water content for the alga and water loss beyond this would cause irreversible damage. The species cannot tolerate increased emersion. Increases in the period of emersion would cause plants to die at the upper limit of the species. Fucus vesiculosus survives readily in fully submerged conditions where lowered salinity reduces the range of competing organisms. However, a reduction in the period of emersion under fully saline conditions may result in the plants at the bottom of the species distribution on the shore being out-competed by algae that normally grow further down the shore and the upper limit of the species distribution may extend up the shore. Recovery would be high due to the high fecundity of the species, its widespread distribution and capacity for dispersal.Fucus vesiculosus recruits readily to cleared areas of the shore although full recovery may take 1-3 years. | Intermediate | High | Low | Moderate |

Decrease in emergence regime [Show more]Decrease in emergence regimeBenchmark. A one hour change in the time covered or not covered by the sea for a period of one year. Further details Evidence | No information | |||

Increase in water flow rate [Show more]Increase in water flow rateA change of two categories in water flow rate (view glossary) for 1 year, for example, from moderately strong (1-3 knots) to very weak (negligible). Further details EvidenceIncrease in water flow rate may cause some of the plants to be torn off the substratum or the plants with substratum to be mobilized. The presence of air bladders increases the species drag making it more vulnerable to being removed. Recovery would be high due to the high fecundity of the species and its widespread distribution and capacity for dispersal.Fucus vesiculosus recruits readily to cleared areas of the shore although full recovery may take 1-3 years. | Intermediate | High | Low | Low |

Decrease in water flow rate [Show more]Decrease in water flow rateA change of two categories in water flow rate (view glossary) for 1 year, for example, from moderately strong (1-3 knots) to very weak (negligible). Further details Evidence | No information | |||

Increase in temperature [Show more]Increase in temperature

For intertidal species or communities, the range of temperatures includes the air temperature regime for that species or community. Further details EvidenceFucus vesiculosus can withstand a wide range of temperatures. Plants have been found to tolerate -30°C in Maine for several weeks and temperatures as high as 30°C (Lüning, 1990). However, at the former temperature, intercellular and extracellular ice crystals form which would cause some damage to the plant (S. Kraan, pers. comm.). The species is well within its temperature range in the UK so would not be affected by a change of 5°C. The species showed no sign of damage during the extremely hot summer of 1983, when the average temperature was 8°C hotter than normal (Hawkins & Hartnoll, 1985). | Tolerant | Not relevant | Not sensitive | High |

Decrease in temperature [Show more]Decrease in temperature

For intertidal species or communities, the range of temperatures includes the air temperature regime for that species or community. Further details Evidence | No information | |||

Increase in turbidity [Show more]Increase in turbidity

EvidenceIncreased turbidity may reduce plant growth rates by reducing light available for photosynthesis. The compensation point for photosynthesis for Fucus vesiculosus was found to be ca. 25 µmol /m /sec along the Gulf of Finland. Below this point, the alga must rely on internal energy reserves to survive. A reduction in turbidity at the level at the benchmark level should have no effect. Once turbidity is restored to normal, the growth rate of the species would be quickly restored. | Low | Immediate | Not sensitive | Moderate |

Decrease in turbidity [Show more]Decrease in turbidity

Evidence | No information | |||

Increase in wave exposure [Show more]Increase in wave exposureA change of two ranks on the wave exposure scale (view glossary) e.g., from Exposed to Extremely exposed for a period of one year. Further details EvidenceFucoids may be torn off the substratum by increased wave action. As exposure increases the fucoid population would become dominated by small juvenile plants. An increase in wave action beyond this would lead to dominance of the community by grazers and barnacles at the expense of fucoids. A reduction in wave action would have little effect as the species is naturally found in sheltered conditions. Recovery would be high upon return to sheltered conditions due to the high fecundity of the species and its widespread distribution and capacity for dispersal.Fucus vesiculosus recruits readily to cleared areas of the shore and full recovery takes 1-3 years (Holt et al., 1997). | Intermediate | High | Low | Moderate |

Decrease in wave exposure [Show more]Decrease in wave exposureA change of two ranks on the wave exposure scale (view glossary) e.g., from Exposed to Extremely exposed for a period of one year. Further details Evidence | No information | |||

Noise [Show more]Noise

EvidenceSeaweeds have no known mechanism for perception of noise. | Tolerant | Not relevant | Not sensitive | Not relevant |

Visual presence [Show more]Visual presenceBenchmark. The continuous presence for one month of moving objects not naturally found in the marine environment (e.g., boats, machinery, and humans) within the visual envelope of the species or community under consideration. Further details EvidenceSeaweeds have no known mechanism of visual perception. | Tolerant | Not relevant | Not sensitive | Not relevant |

Abrasion & physical disturbance [Show more]Abrasion & physical disturbanceBenchmark. Force equivalent to a standard scallop dredge landing on or being dragged across the organism. A single event is assumed for assessment. This factor includes mechanical interference, crushing, physical blows against, or rubbing and erosion of the organism or habitat of interest. Where trampling is relevant, the evidence and trampling intensity will be reported in the rationale. Further details. EvidenceAbrasion may cause damage to the fronds and germlings of Fucus vesiculosus. Abrasion may be caused by human trampling which can have a significant impact on shores, reducing the cover of fucoids (Holt et al., 1997). Recovery would be high upon return to normal conditions due to the high fecundity of the species and its widespread distribution and capacity for dispersal. Fucus vesiculosus recruits readily to cleared areas of the shore and full recovery takes 1-3 years. | Intermediate | High | Low | Moderate |

Displacement [Show more]DisplacementBenchmark. Removal of the organism from the substratum and displacement from its original position onto a suitable substratum. A single event is assumed for assessment. Further details EvidenceFucus vesiculosus is permanently attached to the substratum and would not be able to re-attach itself if removed. Recovery would be high upon return to normal conditions due to the high fecundity of the species and its widespread distribution and capacity for dispersal.Fucus vesiculosus recruits readily to cleared areas of the shore although full recovery may take 1-3 years (Holt et al., 1997). | High | High | Moderate | Moderate |

Chemical pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Intolerance | Recoverability | Sensitivity | Evidence / Confidence | |

Synthetic compound contamination [Show more]Synthetic compound contaminationSensitivity is assessed against the available evidence for the effects of contaminants on the species (or closely related species at low confidence) or community of interest. For example:

The evidence used is stated in the rationale. Where the assessment can be based on a known activity then this is stated. The tolerance to contaminants of species of interest will be included in the rationale when available; together with relevant supporting material. Further details. EvidenceFucoids are generally quite robust in terms of chemical pollution (Holt et al., 1997). However, Fucus vesiculosus is extraordinarily highly intolerant of chlorate, such as from pulp mill effluents. In the Baltic, the species has disappeared in the vicinity of pulp mill discharge points and is affected even at immediate and remote distances (Kautsky, 1992). Recovery would be high upon return to normal conditions due to the high fecundity of the species, its widespread distribution and capacity for dispersal.Fucus vesiculosus recruits readily to cleared areas of the shore although full recovery may take 1-3 years (Holt et al., 1997). | Intermediate | High | Low | Low |

Heavy metal contamination [Show more]Heavy metal contaminationEvidenceFucoids accumulate heavy metals and may be used as indicators to monitor these. It is generally accepted that adult plants are relatively tolerant of heavy metal pollution (Holt et al., 1997). However, local variation exists in the tolerance to copper. Plants from highly copper polluted areas can be very tolerant, while those from unpolluted areas suffer significantly reduced growth rates at 25 micrograms per litre. | Low | High | Low | Moderate |

Hydrocarbon contamination [Show more]Hydrocarbon contaminationEvidenceFucus vesiculosus shows limited intolerance to oil. After the Amoco Cadiz oil spill it was observed that Fucus vesiculosus suffered very little (Floc'h & Diouris, 1980). Indeed, Fucus vesiculosus, may increase significantly in abundance on a shore where grazing gastropods have been killed by oil. However, very heavy fouling could reduce light available for photosynthesis and in Norway a heavy oil spill reduced fucoid cover. Recovery occurred within two years in moderately exposed conditions and four years in shelter (Holt et al., 1997). | Low | High | Low | High |

Radionuclide contamination [Show more]Radionuclide contaminationEvidenceBrown algae readily accumulate radionuclides and have been routinely used in temperate latitudes as biomonitors of radionuclide pollution (van der Ben & Bonotto, 1991; Fowler, 1979, cited in Boisson et al.,1997). In the Irish Sea, much higher activities of alpha and gamma radionuclides were observed at sites in close proximity to Sellafield compared to other sites on the coast (Thompson et al., 1982). Temperature has been shown to affect the uptake of some radionuclides and their subsequent bioaccumulation in Fucus vesiculosus (Boisson et al., 1997). More importantly, any contaminants bioaccumulated in the alga can enter the food chain through, for example, grazers such as sea urchins. In 2003 the Radiological Protection Institute of Ireland produced a study focussing on assessing radioactivity exposure to the public and monitoring radioactivity in the marine environment of the Irish Sea (Ryan et al., 2003). In Fucus vesiculosus, activity concentration of the artificial radionuclide caesium-137 was found to have fallen dramatically since 1983 with concentrations ranging from 1.2-5.8 Bq/kg in 2000/2001. Concentrations of technitium-99 averaged between 264-3905 Bq/kg over the same period and concentrations were shown to have been declining since 1998 (Ryan et al., 2003). However, the actual effects of radionuclide accumulation in the alga are not well documented and accordingly, insufficient information has been suggested for this section. | No information | Not relevant | No information | Not relevant |

Changes in nutrient levels [Show more]Changes in nutrient levelsEvidenceNutrients are essential for algal growth and are often a limiting factor. When plants grow in high densities they are usually competing for nutrients. Increased nutrients may lead to eutrophication, overgrowth by green algae and reduced oxygen levels. However, fucoids appear relatively resistant to sewage and they grow within 20m of an outfall discharging sewage from the Isle of Man (Holt et al., 1997). | Intermediate | High | Low | Moderate |

Increase in salinity [Show more]Increase in salinity

EvidenceFucus vesiculosus tolerates a wide range of salinities, as evidenced by it's penetration into the Baltic. Being an intertidal species it must withstand occasional conditions of hyposalinity during precipitation and hypersalinity during sunny or windy periods. In the UK, the species tolerates salinity down to 11 psu, below which it is replaced by Fucus ceranoides (Suryono & Hardy, 1997). The growth of germlings at 35 ‰ was found to be greatly reduced compared to growth at 31 ‰. Recovery would be high upon return to normal salinity conditions due to the high fecundity of the species and its widespread distribution and capacity for dispersal. Fucus vesiculosus recruits readily to cleared areas of the shore although full recovery may take 1-3 years (Holt et al., 1997). | Low | High | Low | Low |

Decrease in salinity [Show more]Decrease in salinity

Evidence | No information | |||

Changes in oxygenation [Show more]Changes in oxygenationBenchmark. Exposure to a dissolved oxygen concentration of 2 mg/l for one week. Further details. EvidenceInsufficientinformation | No information | Not relevant | No information | Not relevant |

Biological pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Intolerance | Recoverability | Sensitivity | Evidence / Confidence | |

Introduction of microbial pathogens/parasites [Show more]Introduction of microbial pathogens/parasitesBenchmark. Sensitivity can only be assessed relative to a known, named disease, likely to cause partial loss of a species population or community. Further details. EvidenceInsufficientinformation | No information | Not relevant | No information | Not relevant |

Introduction of non-native species [Show more]Introduction of non-native speciesSensitivity assessed against the likely effect of the introduction of alien or non-native species in Britain or Ireland. Further details. EvidenceInsufficientinformation | No information | Not relevant | No information | Not relevant |

Extraction of this species [Show more]Extraction of this speciesBenchmark. Extraction removes 50% of the species or community from the area under consideration. Sensitivity will be assessed as 'intermediate'. The habitat remains intact or recovers rapidly. Any effects of the extraction process on the habitat itself are addressed under other factors, e.g. displacement, abrasion and physical disturbance, and substratum loss. Further details. EvidenceOver harvesting could occur on easily accessible shores if harvesting of Fucus vesiculosus increased significantly. Provided the plant is not removed entirely the algae can regenerate from the remaining stem. Recovery would be high due to the high fecundity of the species and its widespread distribution and capacity for dispersal. Fucus vesiculosus recruits readily to cleared areas of the shore although full recovery may take 1-3 years. | Intermediate | High | Low | Not relevant |

Extraction of other species [Show more]Extraction of other speciesBenchmark. A species that is a required host or prey for the species under consideration (and assuming that no alternative host exists) or a keystone species in a biotope is removed. Any effects of the extraction process on the habitat itself are addressed under other factors, e.g. displacement, abrasion and physical disturbance, and substratum loss. Further details. EvidenceInsufficientinformation | No information | Not relevant | No information | Not relevant |

Additional information

Importance review

Policy/legislation

- no data -

Status

| National (GB) importance | - | Global red list (IUCN) category | - |

Non-native

| Parameter | Data |

|---|---|

| Native | Native |

| Origin | - |

| Date Arrived | - |

Importance information

Morrissey et al (2001) listed many uses for Fucus vesiculosus including fertilizer, bodycare products, such as shower gels and body creams, and health supplements (kelp tablets). When used in hot seawater baths or steamed the plants are said to release certain substances that promote good skin, lower blood pressure and ease arthritic and rheumatic pains (Morrissey et al, 2001). The boiled broth can also be used as a health drink (Guiry & Blunden, 1991). Only a small amount of the available Fucus vesiculosus resource is reported to be used and is hand cut or collected as drift (Morrissey et al, 2001).Fucus vesiculosus is important for promoting biodiversity as it provides substrate and shelter for various species including the tube worm Spirorbis spirorbis, herbivorous isopods, such as Idotea, and surface grazing snails, such as Littorina obtusata.

Bibliography

Bäck, S., Collins, J.C. & Russell, G., 1991. Aspects of the reproductive biology of Fucus vesiculosus from the coast of south west Finland. Ophelia, 34, 129-141.

Berger, R., Malm, T. & Kautsky, L., 2001. Two reproductive strategies in Baltic Fucus vesiculosus (Phaeophyceae). European Journal of Phycology, 36, 265-273.

Boisson, F., Hutchins, D.A., Fowler, S.W., Fisher, N.S. & Teyssie, J.-L., 1997. Influence of temperature on the accumulation and retention of 11 radionuclides by the marine alga Fucus vesiculosus (L.). Marine Pollution Bulletin, 35, 313-321.

Carlson, L., 1991. Seasonal variation in growth, reproduction and nitrogen content of Fucus vesiculosus in the Öresund, Southern Sweden. Botanica Marina, 34, 447-453.

Guiry, M.D. & Blunden, G., 1991. Seaweed Resources in Europe: Uses and Potential. Chicester: John Wiley & Sons.

Guiry, M.D. & Nic Dhonncha, E., 2002. AlgaeBase. World Wide Web electronic publication http://www.algaebase.org,

Hardy, F.G. & Guiry, M.D., 2003. A check-list and atlas of the seaweeds of Britain and Ireland. London: British Phycological Society

Hawkins, S.J. & Hartnoll, R.G., 1985. Factors determining the upper limits of intertidal canopy-forming algae. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 20, 265-271.

Hiscock, S., 1979. A field key to the British brown seaweeds (Phaeophyta). Field Studies, 5, 1- 44.

Holt, T.J., Hartnoll, R.G. & Hawkins, S.J., 1997. The sensitivity and vulnerability to man-induced change of selected communities: intertidal brown algal shrubs, Zostera beds and Sabellaria spinulosa reefs. English Nature, Peterborough, English Nature Research Report No. 234.

Howson, C.M. & Picton, B.E., 1997. The species directory of the marine fauna and flora of the British Isles and surrounding seas. Belfast: Ulster Museum. [Ulster Museum publication, no. 276.]

Kautsky, H., 1992. The impact of pulp-mill effluents on phytobenthic communities in the Baltic Sea. Ambio, 21, 308-313.

Knight, M. & Parke, M., 1950. A biological study of Fucus vesiculosus L. and Fucus serratus L. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 29, 439-514.

Morrissey, J., Kraan, S. & Guiry, M.D., 2001. A guide to commercially important seaweeds on the Irish coast. Bord Iascaigh Mhara: Dun Laoghaire.

Munda, I.M., 1997. Combined effects of temperature and salinity on growth rates of germlings of three Fucus species from Iceland, Helgoland and the North Adriatic Sea. Helgoländer Wissenschaftliche Meeresunters, 29, 302-310.

Ryan, T.P., McMahon, C.A., Dowdall, A., Fegan, M., Sequeira, S., Murray, M., McKittrick, L., Hayden, E., Wong, J. & Colgan, P.A., 2003. Radioactivity monitoring of the marine environment 2000 and 2001. , Radiological Protection Institute of Ireland., http://www.rpii.ie/reports/2003/MarineReport20002001final.pdf

Serrão, E.A., Kautsky, L., Lifvergren, T. & Brawley, S.H., 1997. Gamete dispersal and pre-recruitment mortality in Baltic Fucus vesiculosus (Abstract only). Phycologia, 36 (Suppl.), 101-102.

Strömgren, T., 1977. Short-term effects of temperature upon the growth of intertidal fucales. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 29 (2), 181-195. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0981(77)90047-8

Suryono, C.A. & Hardy, F.G., 1997. Studies on the distribution of Fucus ceranoides L. (Phaeophyta, Fucales) in estuaries on the north-east coast of England. Transactions of the Natural History Society of Northumbria, 57, 153-168.

Thompson, N., Cross, J.E., Miller, R.M. & Day, J.P., 1982. Alpha and gamma radioactivity in Fucus vesiculosus from the Irish Sea. Environmental Pollution (Serries B), 3, 11-19.

Van der Ben, D. & Bonotto, S., 1991. Utilization of brown algae for monitoring the radioactive contamination of the marine environment. Oebalia, 17, 143-153.

Wippelhauser, G.S., 1996. Ecology and management of Maine's eelgrass, rockweed, and kelps. Augusta: Department of Conservation.

Datasets

Bristol Regional Environmental Records Centre, 2017. BRERC species records recorded over 15 years ago. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/h1ln5p accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-09-25.

Bristol Regional Environmental Records Centre, 2017. BRERC species records within last 15 years. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/vntgox accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-09-25.

Centre for Environmental Data and Recording, 2018. Ulster Museum Marine Surveys of Northern Ireland Coastal Waters. Occurrence dataset https://www.nmni.com/CEDaR/CEDaR-Centre-for-Environmental-Data-and-Recording.aspx accessed via NBNAtlas.org on 2018-09-25.

Cofnod – North Wales Environmental Information Service, 2018. Miscellaneous records held on the Cofnod database. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/hcgqsi accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-09-25.

Environmental Records Information Centre North East, 2018. ERIC NE Combined dataset to 2017. Occurrence dataset: http://www.ericnortheast.org.ukl accessed via NBNAtlas.org on 2018-09-38

Fenwick, 2018. Aphotomarine. Occurrence dataset http://www.aphotomarine.com/index.html Accessed via NBNAtlas.org on 2018-10-01

Fife Nature Records Centre, 2018. St Andrews BioBlitz 2014. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/erweal accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-09-27.

Fife Nature Records Centre, 2018. St Andrews BioBlitz 2015. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/xtrbvy accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-09-27.

Fife Nature Records Centre, 2018. St Andrews BioBlitz 2016. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/146yiz accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-09-27.

Kent Wildlife Trust, 2018. Biological survey of the intertidal chalk reefs between Folkestone Warren and Kingsdown, Kent 2009-2011. Occurrence dataset: https://www.kentwildlifetrust.org.uk/ accessed via NBNAtlas.org on 2018-10-01.

Kent Wildlife Trust, 2018. Kent Wildlife Trust Shoresearch Intertidal Survey 2004 onwards. Occurrence dataset: https://www.kentwildlifetrust.org.uk/ accessed via NBNAtlas.org on 2018-10-01.

Lancashire Environment Record Network, 2018. LERN Records. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/esxc9a accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

Manx Biological Recording Partnership, 2017. Isle of Man wildlife records from 01/01/2000 to 13/02/2017. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/mopwow accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

Manx Biological Recording Partnership, 2018. Isle of Man historical wildlife records 1990 to 1994. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/aru16v accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

Manx Biological Recording Partnership, 2018. Isle of Man historical wildlife records 1995 to 1999. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/lo2tge accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

Merseyside BioBank., 2018. Merseyside BioBank (unverified). Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/iou2ld accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

National Trust, 2017. National Trust Species Records. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/opc6g1 accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

NBN (National Biodiversity Network) Atlas. Available from: https://www.nbnatlas.org.

Norfolk Biodiversity Information Service, 2017. NBIS Records to December 2016. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/jca5lo accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

OBIS (Ocean Biodiversity Information System), 2025. Global map of species distribution using gridded data. Available from: Ocean Biogeographic Information System. www.iobis.org. Accessed: 2025-07-15

Outer Hebrides Biological Recording, 2018. Non-vascular Plants, Outer Hebrides. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/goidos accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-01.

Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, 2018. Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh Herbarium (E). Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/ypoair accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-02.

South East Wales Biodiversity Records Centre, 2018. SEWBReC Algae and allied species (South East Wales). Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/55albd accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-02.

South East Wales Biodiversity Records Centre, 2018. Dr Mary Gillham Archive Project. Occurance dataset: http://www.sewbrec.org.uk/ accessed via NBNAtlas.org on 2018-10-02

Suffolk Biodiversity Information Service., 2017. Suffolk Biodiversity Information Service (SBIS) Dataset. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/ab4vwo accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-02.

The Wildlife Information Centre, 2018. TWIC Biodiversity Field Trip Data (1995-present). Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/ljc0ke accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-02.

Yorkshire Wildlife Trust, 2018. Yorkshire Wildlife Trust Shoresearch. Occurrence dataset: https://doi.org/10.15468/1nw3ch accessed via GBIF.org on 2018-10-02.

Citation

This review can be cited as:

Last Updated: 29/05/2008