Eunicella verrucosa and Pentapora foliacea on wave-exposed circalittoral rock

| Researched by | John Readman, Angus Jackson, Dr Keith Hiscock, Kelsey Lloyd & Amy Watson | Refereed by | Dr Keith Hiscock |

|---|

Summary

UK and Ireland classification

Description

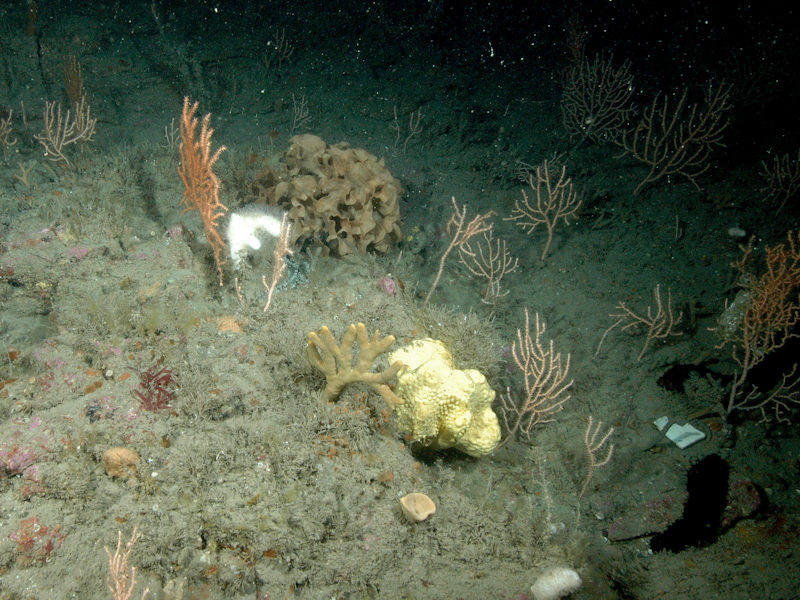

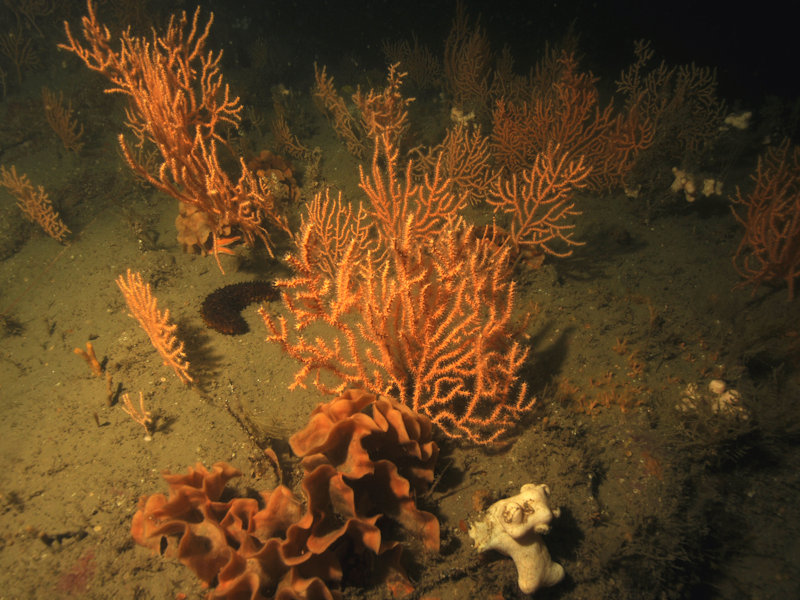

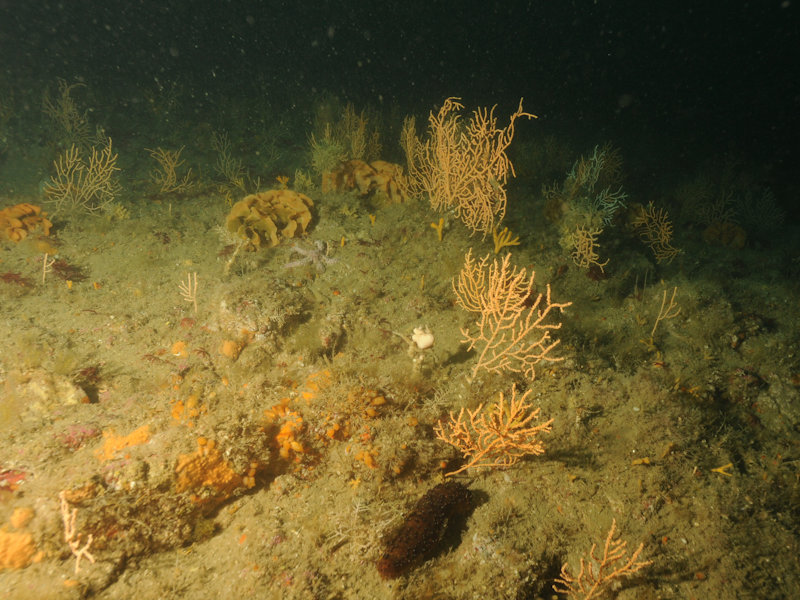

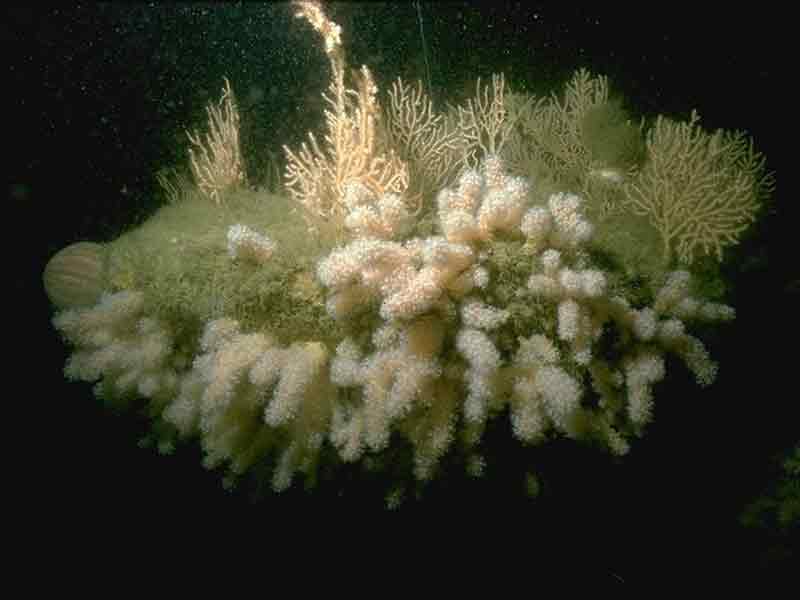

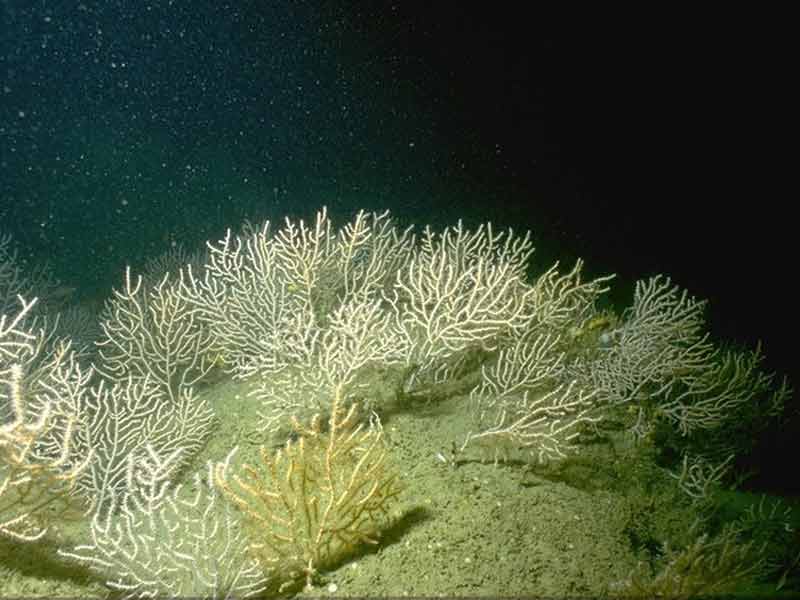

This variant typically occurs on wave-exposed, steep, circalittoral bedrock, boulder slopes and outcrops, subject to varying tidal streams. This silty variant contains a diverse faunal community, dominated by the seafan Eunicella verrucosa, the bryozoan Pentapora foliacea and the cup coral Caryophyllia smithii. There are frequently numerous Alcyonium digitatum, and these may become locally abundant under more tide-swept conditions. Alcyonium glomeratum may also be present. A diverse sponge community is usually present, including numerous erect sponges; species present include Cliona celata, Raspailia ramosa, Raspailia hispida, Axinella dissimilis, Stelligera stuposa, Dysidea fragilis and Polymastia boletiformis. Homaxinella subdola may be present in the south-west. A hydroid/bryozoan turf may develop in the understorey of this rich sponge assemblage, with species such as Nemertesia antennina, Nemertesia ramosa, crisiids, Alcyonidium diaphanum and Crisularia plumosa. The sea cucumber Holothuria (Panningothuria) forskali may be locally abundant, feeding on the silty deposits on the rock surface. Other echinoderms encountered include the starfish Marthasterias glacialis and the urchin Echinus esculentus. Other fauna includes aggregations of colonial ascidians Clavelina lepadiformis and Stolonica socialis. Anemones such as Actinothoe sphyrodeta and Parazoanthus axinellae may be seen dotted across the rock surface. This biotope is present in south-west England and Wales. (Information from Connor et al., 2004; JNCC, 2105).

Depth range

10-20 m, 20-30 mAdditional information

-

Listed By

Habitat review

Ecology

Ecological and functional relationships

- The biotopes represented by MCR.ErSEun are sponge and soft coral dominated. Sponges are noted as being inhabited by a wide diversity of invertebrates. Sponges can provide hard substrata for attachment, refugia and shelter, an enhanced food supply in feeding currents and a potential food source themselves (Klitgaard, 1995; Koukouras et al., 1996.)

- The fauna associated with sponges in temperate to cold waters is considered to be facultative rather than obligate and reflects the fauna of the local geographic area (Klitgaard, 1995)

- Predation levels of the characterizing species in the biotope are poorly understood. Eunicella verrucosa is preyed upon by the sea slug Duvaucelia odhneri and Alcyonium digitatum by Tritonia plebeia. Alcyonium digitatum and Alcyonium glomeratum are preyed upon by the prosobranch Simnia patula Grazing by the sea urchin Echinus esculentus may modify faunal abundance and distribution. Some species of temperate sponge contain chemicals that can inhibit sea urchin feeding (Wright et al., 1997)

- Large colonies of Pentapora foliacea with their complex laminar structure are noted as potentially sheltering thousands of other animals. Pentapora fascialis in the Mediterranean supports various epibiotic species, some of which may cause partial mortality of colonies (Cocito et al., 1998(a)).

- The various mobile echinoderms characteristic of the biotope (e.g. Luidia ciliaris, Henricia oculata, Asterias rubens) may have a role in modifying other benthic populations through predation.

- Eunicella verrucosa provides a habitat for the nationally rare sea anemone Amphianthus dohrnii.

- Where the deposit feeding sea cucumber, the cotton spinner Holothuria (Panningothuria) forskali occurs, it may be important in removing silt and enabling settlement of other benthic species.

Seasonal and longer term change

Annual species in the biotope such as Nemertesia ramosa will increase and decrease through the seasons. Other species such as Alcyonium digitatum have seasonal stages, retracting their polyps and not feeding from about July to November, during which time the surface of the colony becomes covered with encrusting algae and hydroids (Fish & Fish, 1996). When the colony recommences feeding in December the surface film, together with the surface epithelium, is shed. The main species used to represent the biotope, Eunicella verrucosa, Axinella dissimilis, & Pentapora foliacea are typically long-lived perennials. Where the biotope occurs in the lower infralittoral or upper circalittoral, extensive growth of annual algae may occur, especially in years when the water is clear.

Habitat structure and complexity

Many of the species characteristic of this community add considerable physical complexity to the biotope. There are upright branching and cup sponges, sea fans, colonies of dead mans fingers and erect bryozoans. All of these species add depth and a three dimensional structure to the substratum. The biotope occurs on bedrock and boulders which may provide overhangs, crevices and shelter where crevice dwelling species such as sea cucumbers (Aslia lefevrei), squat lobsters and wrasse (mainly Centrolabrus exoletus) may live. Complex upright bryozoans as well as many sponges are recorded as providing substratum and shelter for other species . Sponge morphology is important in determining the number and abundance of inhabitant species. Sponges with a spicule 'fur' have more associated taxa than sponges without (Klitgaard, 1995). For example, Axinella species have a spicule 'fur' (Moss & Ackers, 1982). Hayward & Ryland, (1979) record large colonies of Pentapora foliacea as potentially sheltering thousands of other animals.

- The biotope MCR.PhaAxi has a similar sponge component to MCR.ErSEun but has different associated fauna and occurs in deeper water with greater wave exposure.

- MCR.ErSPbolSH is again a sponge dominated biotope with an understorey of hydroids and bryozoans. Although still on fairly stable substrata some of the species present are associated with more ephemeral or disturbed biotopes.

Productivity

No photosynthetic species are listed as characterizing species in MCR.ErSEun, a circalittoral biotope. Consequently, primary production is not regarded as a major component of productivity. Nevertheless, some characteristically deep water species of algae are often present and near to the infralittoral algae may sometimes be abundant. The biotopes MCR.ErSPbolSH and MCR.ErSSwi may have a small algal component. The biotopes are often species rich and may contain quite high animal densities and biomass. Specific information about the productivity of characterizing species or about the biotopes in general are not available.

Recruitment processes

Most of the characterizing species in the biotope are sessile suspension feeders. Recruitment of adults of these species to the biotope by immigration is unlikely. Consequently, recruitment must occur primarily through dispersive larval stages. Some species have larvae that can disperse widely and these may arrive from distant locations. Other species such as Pentapora foliacea have larvae that typically exist for only a short time and will settle in the proximity of the parent (Cocito et al., 1998b). Recruitment of the mobile predators and grazers may be through immigration of adults or via a larval dispersal phase.

Time for community to reach maturity

Some species within the biotope community are annuals and recruit each year (e.g. Nemertesia ramosa). Other species are potentially very slow growing and long lived such as Eunicella verrucosa which may live as long as 50 years (K. Hiscock pers. comm.).

Additional information

The main trophic group in the biotope is suspension feeders although there may be several species of fish and echinoderm predators or grazers present.

Preferences & Distribution

Habitat preferences

| Depth Range | 10-20 m, 20-30 m |

|---|---|

| Water clarity preferences | No information |

| Limiting Nutrients | No information |

| Salinity preferences | Full (30-40 psu) |

| Physiographic preferences | Open coast |

| Biological zone preferences | Circalittoral |

| Substratum/habitat preferences | Bedrock |

| Tidal strength preferences | Moderately strong 1 to 3 knots (0.5-1.5 m/sec.) |

| Wave exposure preferences | Exposed, Extremely exposed, Moderately exposed, Very exposed |

| Other preferences |

Additional Information

Recorded distribution is only for the representative biotope MCR.ErSEun. For recorded distributions of the other biotopes represented by this review see MERMAID. Apart from perhaps MCR.ErSSwi, the biotopes represented by this review have a silt component suggesting that localized shelter may be important in encouraging their development.Species composition

Species found especially in this biotope

Rare or scarce species associated with this biotope

-

Additional information

Sensitivity review

Sensitivity characteristics of the habitat and relevant characteristic species

CR.HCR.XFa.ByErSp.Eun is dominated by the sea fan Eunicella verrucosa, the bryozoan Pentapora foliacea and the cup coral Caryophyllia smithii. It occurs in variable water movement on wave exposed steep circalittoral bedrock and boulders subject to silt as it is surrounded by coarse sediment. Eunicella verrucosa is a widespread species in south-west England and it is often the associated species that are unusual. It is host to the sea fan anemone Amphianthus dohrnii, the sea fan cowrie Simnia hiscocki and the sea fan sea slug Tritonia nilsohdneri which are nationally scarce and do not occur, or very rarely occur, away from sea fans. Other species that favour the sea fan are the hydroid Antenella secundaria, the barnacle Hesperibalanus fallax and the ascidian Pycnoclavella aurilucens. They depend on the presence of the sea fan, and would be lost if their host was lost. In addition, there are many species present in this biotope that are nationally scarce or uncommon and that are likely slow-growing, persistent and unlikely to recover if lost. They include the sponges Axinella damicornis, Adreus fascicularis, and the yellow cluster anemone Parazoanthus axinellae (Keith Hiscock, pers. comm.)

Therefore the sensitivity assessment is focused on the sensitivity of the characterizing sea fan Eunicella verrucosa, bryozoan Pentapora fascialis, cup coral Caryophyllia smithii, and the fragile erect sponge Axinella dissimilis.Resilience and recovery rates of habitat

Eunicella verrucosa forms large colonies that branch profusely, mostly in one plane up to 30 cm tall and 40 cm wide, and may grow slowly in British waters, approximately 1 cm per year (Bunker, 1984; Picton & Morrow, 2005). Settlement of Eunicella verrucosa occurred in the fourth year after ex-HMS Scylla was placed on the seabed near Plymouth. Growth was initially rapid and fans had reached 6 cm in height by the end of the first winter and some were 17 cm high by the beginning of the next winter, often with several branches (Hiscock et al., 2010). By 2017, many were about 20 cm high and extensively branched (Keith Hiscock, pers. comm.) There is no specific information on reproduction in Eunicella verrucosa but the larvae of Eunicella singularis are most likely lecithotrophic and have a short life (several hours to several days) (Weinberg & Weinberg, 1979). Recruitment in gorgonians is often reported to be sporadic and/or low (Yoshioka 1996; Lasker et al. 1998; Coma et al. 2006). Eunicella verrucosa has been known to colonize wrecks at least several hundred metres from other hard substrata but is thought to have larvae that generally settle near the parent (Hiscock, 2007). Growth rate can be highly variable. An increase in branch length of up to 6 cm was reported for some branches in one year but virtually none in others in Lyme Bay populations over a year (C. Munro, pers. comm. cited in Hiscock, 2007). In the morphologically similar Paramuricea clavata in the Mediterranean, Coma et al. (1995) described reproduction and the cycle of gonad development. Spawning occurred 3-6 days after the full or new moon in summer. Spawned eggs adhered to a mucus coating on female colonies; a feature that would be expected to have been readily observed if it occurred in Eunicella verrucosa. Maturation of planulae took place among the polyps of the parent colony and, on leaving the colony, planulae immediately settled on surrounding substrata. It seems more likely that planulae of Eunicella verrucosa are released immediately from the polyps and are likely to drift (Hiscock, 2007). Coma et al. (2006) reported ongoing recovery in Eunicella singularis populations in the Mediterranean four years following a mass-mortality event. Although not recovered, Sheehan et al. (2013) noted that within three years of closing an area in Lyme Bay, the UK to fishing, some recovery of Eunicella verrucosa had occurred, with a marked increase compared to areas that were still fished.

Pentapora foliacea is an erect perennial bryozoan (Eggleston, 1972; Hayward & Ryland, 1995). Whilst Hayward & Ryland (1999) conflated Pentapora foliacea and Pentapora fascialis, Lombardi et al. (2010) concluded that Pentapora foliacea and Pentapora fascialis were distinct species and that Pentapora foliacea was the resident species in the North East Atlantic while Pentapora fascialis was included in the Mediterranean clade. Given the similarity between these two species and the taxonomic confusion in the literature, this assessment uses information on both Pentapora foliacea and Pentapora fascialis.

Pentapora fascialis was recorded to recover in 3.5 years after the almost total loss of a local population (Cocito et al., 1998). The species was reported to repair damage to the colony through regrowth of new zooids and strengthening of the base by thickening of lower zooid walls (Hayward and Ryland, 1979). Colonies are typically 20 cm in diameter but can grow up to 2 m in diameter and reach a height of 30 cm in the British Isles (Hayward & Ryland, 1979). Colonies of Pentapora fascialis as small as 2.8 cm have been recorded as having ovicells, with reproduction possible from an early stage of colony development (Cocito et al., 1998 cited in Jackson, 2016). Lock et al. (2006) describes the growth of Pentapora foliacea in Skomer, Wales as highly variable, with some colonies growing 800 cm² in a year whilst other large colonies completely disappeared. Recovery to pre-disturbance levels following a severe heat event, which resulted in the decline of 86% in live colony portion of Pentapora fascialis in the Mediterranean, took four years (Cocito & Sgorbini, 2014). Pentapora fascialis was first observed colonising ex-HMS Scylla 20 months after the vessel was placed on the seabed and colonies had grown to ca 20 cm diameter within three years of colonization (Hiscock et al., 2010).

Caryophyllia smithii is a small (max 3 cm across) solitary coral, common within tide swept sites of the UK (Wood, 2005), but was common on the cliffs within Lough Hyne which experience little water movement (Hiscock, pers comm.) It is distributed from Greece (Koukouras, 2010) to the Shetland Islands and southern Norway (Wilson, 1975; NBN, 2015). It was suggested by Fowler & Laffoley (1993) that Caryophyllia smithii was a slow growing species (0.5-1 mm in horizontal dimension of the corallum per year), which in turn suggested that inter-specific spatial competition with colonial faunal or algae species were important factors in determining local abundance of Caryophyllia smithii (Bell & Turner, 2000). Caryophyllia smithii was first observed colonising the wreck of the ex-HMS Scylla in September 2005, eighteen months after the vessel was placed on the seabed near Plymouth. The coral was still only occasional on the reef after five years (Hiscock et al., 2010). Caryophyllia smithii reproduces sexually; sessile polyps discharge gametes typically from January-April. Gamete release is probably triggered by seasonal temperature increases. Gametes are fertilized in the water column and develop into a swimming planula that then settles onto suitable substrata. The pelagic stage of the larvae may last up to 10 weeks, which provides this species with a good dispersal capability (Tranter et al., 1982). Caryophyllia smithii reproduces between January and March; spawning occurs from March to June (Tranter et al., 1982). However, asexual reproduction and division are commonly observed (Hiscock & Howlett, 1976).

Fowler & Laffoley (1993) studied the sessile epifauna near Lundy and found that the growth rates for branching sponges were irregular, but generally very slow, with apparent shrinkage in some years (notably between 1985 and 1986). Monitoring studies at Lundy (Hiscock, 1994; Hiscock, 2003; Hiscock, pers comm) suggested that growth of Axinella dissimilis (as Axinella polypoides) was no more than about 2 mm a year (up to a height of ca 30 cm) and that all branching sponges included in photographic monitoring over a period of four years exhibited very little or no growth over the study. In addition, no recruitment of Axinellia dissimilis (or Axinellia infundibuliformis) was observed.

Resilience assessment

Bryozoans tend to be fast-growing fauna that are capable of self-regeneration. Dispersal of the larvae is limited and whilst it is likely that the bryozoan turfs would regenerate rapidly for most levels of damage. Caryophyllia smithii was first observed colonising the wreck of the ex-HMS Scylla in September 2005, eighteen months after the vessel was placed on the seabed near Plymouth. The coral was occasional on the reef after five years (Hiscock et al., 2010).

Eunicella verrucosa has been described as slow growing in the British Isles (Picton & Morrow, 2005) and recovery is likely to be slow following population collapses. Recent studies, including a mass mortality event in the Mediterranean (Coma et al., 2006) and creation of a no-take zone in Lyme Bay (Sheehan et al., 2013), have reported some recovery within the first few years.

Given their slow growth rate and the lack of observed recovery or recruitment in some axinellids (Hiscock, 1994; Hiscock, 2003; Hiscock, pers comm), any perturbation resulting in mortality of the fragile sponge Axinella dissimilis is likely to result in negligible recovery within 25 years. Resilience is, therefore, classed as Very low (recovery >25 years) for resistance values of None, Low or Medium. Confidence is assessed as ‘Medium’.

Hydrological Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Temperature increase (local) [Show more]Temperature increase (local)Benchmark. A 5°C increase in temperature for one month, or 2°C for one year. Further detail EvidenceEunicella verrucosa has been recorded in the Western Mediterranean and off north-west Africa (Wells et al., 1983 cited in Koomen & Helsdingen, 1996) so that an increase in temperature is not likely to negatively affect the species. However, during the last decades, mass mortality events related to high seawater temperature anomalies have been reported within the Western Mediterranean basin. A mass mortality event in 1999 affected many gorgonians, although Eunicella verrucosa near Gallinaria Island was ‘little affected’ (Cerrano et al. 2000). ‘Occassional’ mortality was observed in the shallowest populations along the Provence coast (at 37-38 m) during a high temperature event in 1999 where sea temperature was 23-24°C throughout the water column to 40m depth (Perez et al. 2000). In 2003, the pink sea fan populations were affected in the Gulf of Genoa but not along the Provence coast (Garrabou et al. 2009). Although total mortality was not explicitly reported for this species, a certain reduction in population size could be suspected, due to delayed mortality of colonies affected by high levels of injury, as observed in some other Mediterranean gorgonians (e.g. Linares et al.,2005; Coma et al., 2006). Cocito & Sgorbini (2014) studied spatial and temporal patterns of colonial bryozoans in the Ligurian Sea over nine years. High temperature events caused mass mortality among a number of species. The decline in Pentapora fascialis colony cover between 11 and 22 m depth followed the unusually warm summer in 1999 (temperature at 11 m of 23.87 ± 1.4 °C) with a 86% reduction in live colony portion and the larger colonies were most affected. Gradual recovery took place, with deeper communities recovering to pre-disturbance levels within four years. Caryophyllia smithii is found across the British Isles (NBN, 2015) and has been recorded in Greece (Koukouras, 2010). It is therefore unlikely to be significantly affected at the benchmark. However, Tranter et al. (1982) suggested Caryophyllia smithii reproduction was cued by seasonal increases in seawater temperature. Therefore unseasonal increases in temperature may disrupt natural reproductive processes and negatively influence recruitment patterns. Sensitivity assessment Eunicella verrucosa, Pentapora foliacea, Caryophyllia smithii, and Axinella dissimilis are distributed throughout the UK, with the distribution of some of the species as far south as the Mediterranean. A long-term increase in temperature may result in an increase in abundance of some of the characterising species. Resistance is therefore assessed as ‘High’, resilience as ‘High’ and the biotope assessed as ‘Not sensitive’ at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Temperature decrease (local) [Show more]Temperature decrease (local)Benchmark. A 5°C decrease in temperature for one month, or 2°C for one year. Further detail EvidenceEunicella verrucosa is a southern species, distribution is generally limited to the south west of the British Isles (Hayward & Ryland, 1990; NBN, 2015). A decrease in temperature is likely to result in mortality. However, A live specimen collected from shallow depths off North Devon in 1973 exhibited growth rings that demonstrated that the colony had survived the 1962/63 cold winter(Hiscock, pers comm.). Also, large colonies were collected (for sale as souvenirs) from Lundy in the late 1960's suggesting no significant loss in 1962/63 (Hiscock, 2007). Assuming that temperature decrease reduces recruitment, the population size might decline for a year but recovery would occur following successful recruitment. Pentapora foliacea is found as far north the Minch off western Scotland (Lombardi et al., 2010). Patzold et al. (1987) recorded the formation of growth bands in Pentapora foliacea during times of reduced reproduction, which appeared during periods of colder water temperatures. Once established, colonies are most likely able to withstand occasional lower or higher than normal temperatures, but long-term decreases in temperature may cause distribution range to shrink. Whilst Caryophyllia smithii is a southern species (Fish & Fish, 1996) it occurs in the Shetland Isles (NBN, 2015) whereas CR.HCR.Xfa.ByErSp.Eun is concentrated in the south and west of the UK. The British Isles is at the northern distribution limit of Axinella dissimilis (Ackers et al., 1992). Apparent shrinkage of individual sponges (negative growth rate) observed in Lundy in some years was attributed to particularly cold winters, notably between 1985 and 1986 (Hiscock, 1993). Long-term increases in temperature may cause extension of the British Isles populations and decreases in temperature may result in population shrinkage. Sensitivity assessment Eunicella verrucosa, already close to its northern distribution limit, would likely suffer mortality in the event of a decrease in temperature, however, it appears to have survived the 1962/3 winter and may have some resistance to temporary changed. Apparent shrinkage of individual Axinella dissimilis (negative growth rate) was observed in Lundy in some years and was attributed to particularly cold winters, notably between 1985 and 1986 (Hiscock, 1993). Resistance is therefore assessed as ‘Medium’, resilience as ‘Very Low’ and sensitivity as ‘Medium’. | MediumHelp | Very LowHelp | MediumHelp |

Salinity increase (local) [Show more]Salinity increase (local)Benchmark. A increase in one MNCR salinity category above the usual range of the biotope or habitat. Further detail EvidenceCR.HCR.XFa.ByErSp.Eun is a circalittoral biotope and an increase in salinity at the benchmark level would result in a change from full to hypersaline conditions. No records of Eunicella verrucosa, Caryophyllia smithii, or Axinella dissimilis in hypersaline conditions was found. Chesher (1975) monitored the species surrounding a desalination outfall with brine effluent at 52‰ salinity, together with variable concentrations of copper and nickel. As a group gorgonians were noted to survive brief exposure to 4-5% effluent, however, long-term survival decreased in relation to proximity to the outfall. Whilst no evidence for the characterizing species was found, there is evidence of gorgonian mortality due to hypersaline effluent. Resistance is therefore probably ‘Low’, resilience ‘Very Low’ and sensitivity is ‘High’. | LowHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Salinity decrease (local) [Show more]Salinity decrease (local)Benchmark. A decrease in one MNCR salinity category above the usual range of the biotope or habitat. Further detail EvidenceRyland (1970) stated that, with a few exceptions, the Gymnolaemata were fairly stenohaline and restricted to full salinity (30-35 ppt), noting that reduced salinities result in an impoverished bryozoan fauna. For example, Flustra foliacea appears to be restricted to areas with high salinity (Tyler-Walters & Ballerstedt, 2007; Budd, 2008). Dyrynda (1994) noted that Flustra foliacea and Alcyonidium diaphanum were probably restricted to the vicinity of the Poole Harbour entrance by their intolerance to reduced salinity. Although protected from extreme changes in salinity due to their subtidal habitat, severe hyposaline conditions could adversely affect Flustra foliacea colonies. However, Novosel et al. (2004) described large colonies of Pentapora fascialis growing inside the plumes of marine freshwater springs (3 psu lower than water outside of the channel). Eunicella verrucosa has only been recorded in Full salinity biotopes while Caryophyllia smithii has been recorded in biotopes from Full to Low salinity (Connor et al., 2004) and would probably tolerate a change at the benchmark level. No information was found for Axinella dissimilis in water with salinity below 30-40. Sensitivity assessment. Pentapora foliacea, Eunicella verrucosa (together with associated species), and Axinella dissimilis would probably be affected adversely by a decrease in salinity at the benchmark level and resistance is ‘Low’, resilience is ‘Very low’ and sensitivity is ‘High’. | LowHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Water flow (tidal current) changes (local) [Show more]Water flow (tidal current) changes (local)Benchmark. A change in peak mean spring bed flow velocity of between 0.1 m/s to 0.2 m/s for more than one year. Further detail EvidenceCR.HCR.XFa.ByErSp.Eun consists mainly of species firmly attached to the substratum and which would be unlikely to be displaced by an increase in the strength of tidal streams at the benchmark level. Sea fans are found in strong tidal streams but most likely retract their polyps when current velocity gets too high for the polyps to retain food. Tidal streams exert a steady pull on the colonies and are therefore likely to detach only very weakly attached colonies. Colonies rely on water flow to bring food and to remove silt (Hiscock, 2007). Water flow has been shown to be important for the development of bryozoan communities and the provision of suitable hard substrata for colonization (Eggleston, 1972b; Ryland, 1976). In addition, areas subject to the high mass transport of water such as the Menai Strait and tidal rapids generally support large numbers of bryozoan species (Moore, 1977a). Although bryozoans are active suspension feeders, feeding currents are probably fairly localized and they are dependent on water flow to bring adequate food supplies within reach (McKinney, 1986). A substantial decrease in water flow will probably result in impaired growth due to a reduction in food availability, and an increased risk of siltation (Tyler-Walters, 2005). Caryophyllia smithii, is a suspension feeder, relying on water currents to supply food (Hiscock, 1983). These taxa, therefore, thrive in conditions of vigorous water flow e.g. around Orkney and St Abbs, Scotland, where Alcyonium digitatum dominated biotopes may experience tidal currents of 3 and 4 knots (approximately 1.5 m/sec) during spring tides (De Kluijver, 1993). Caryophyllia smithii, in particular, is described as favouring sites with a high tidal flow (Bell & Turner, 2000; Wood, 2005). Riisgard et al. (1993) discussed the low energy cost of filtration for sponges and concluded that passive current-induced filtration may be of insignificant importance for sponges. However, water movement is probably required to ensure supply of food (particulates and dissolved organic matter) as well as oxygen. The sponges Axinella spp. were recorded in biotopes that experienced very weak flow to moderate (0-1.5 m/s) (Connor et al., 2004). Eunicella verrucosa, Caryophyllia smithii and Pentapora foliacea have been recorded in biotopes ranging from very weak to strong water flow (0-3 m/s) (Connor et al., 2004). Sensitivity assessment. CR.HCR.XFa.ByErSp.Eun is found in moderately strong water flow (1-3 knots) and, whilst a significant decrease could result in less favourable conditions for Eunicella verrucosa, a change at the benchmark level (0.1-0.2 m/s) is unlikely to affect the characterizing species. Resistance is therefore ‘High’, resilience is ‘High’ and the biotope is ‘Not Sensitive’. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Emergence regime changes [Show more]Emergence regime changesBenchmark. 1) A change in the time covered or not covered by the sea for a period of ≥1 year or 2) an increase in relative sea level or decrease in high water level for ≥1 year. Further detail EvidenceChanges in emergence are Not Relevant to this biotope as it is restricted to fully subtidal/circalittoral conditions - the pressure benchmark is relevant only to littoral and shallow sublittoral fringe biotopes. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Wave exposure changes (local) [Show more]Wave exposure changes (local)Benchmark. A change in near shore significant wave height of >3% but <5% for more than one year. Further detail EvidenceEunicella verrucosa occurs in biotopes that are extremely wave exposed (Connor et al., 2004). Bunker (1986) reported that Eunicella verrucosa was most abundant in moderately exposed locations. However, dead sea fans have been recorded washed up along Chesil Beach (UK) following winter storms (Hatcher and Trewhella, 2006 cited in Wood, 2015b). Caryophyllia smithii has been recorded in very sheltered to extremely exposed biotopes (Connor et al., 2004). Pentapora foliacea is recorded as occurring in biotopes experiencing moderate to extreme wave exposure (Connor et al., 2004). However, extreme wave action (storms) has been noted to cause widespread destruction of colonies (Cocito et al., 1998a). Significant increases in wave exposure may, therefore, cause damage to colonies. Hiscock (2003) suggested that ‘prolonged Easterly gales in 1985’ might account for the loss of Axinella dissimilis specimens at Lundy. Nevertheless, following severe gales in 2013/1014, the abundance of sea fans, Pentapora fascialis, and associated branching sponges on stable rocky habitats appeared much as always (Hiscock, pers. comm.) Sensitivity assessment. CR.HCR.XFa.ByErSp.Eun occurs across a number of wave exposures, from moderate to extremely exposed. A decrease in wave exposure, e.g. due to artificial barriers, may be detrimental as the biotope is dependent on strong water flow. While storms may cause mortality, a 3-5% change in significant wave height is unlikely to result in any impact in a wave exposed biotope. Resistance is ‘High’, resilience is ‘High’ and the biotope is ‘Not Sensitive’ at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Chemical Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Transition elements & organo-metal contamination [Show more]Transition elements & organo-metal contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceChan et al. (2012) studied the response of the gorgonian Subergorgia suberosa to heavy metal-contaminated seawater from a former coastal mining site in Taiwan. Cu, Zn, and Cd each showed characteristic bioaccumulation. Metallic Zn accumulated but rapidly dissipated. In contrast, Cu easily accumulated but was slow to dissipate, and Cd was only slowly absorbed and dissipated. Associated polyp necrosis, mucus secretion, tissue expansion, and increased mortality were reported in Subergorgia suberosa exposed to water polluted with heavy metals.However, this pressure is Not assessed. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Hydrocarbon & PAH contamination [Show more]Hydrocarbon & PAH contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed but evidence is presented where available. CR.HCR.XFa.ByErSp.Eun is a sub-tidal biotope complex (Connor et al., 2004). Oil pollution is mainly a surface phenomenon and its impact on circalittoral turf communities is likely to be limited. However, as in the case of the Prestige oil spill off the coast of France, high swell and winds can cause oil pollutants to mix with the seawater and potentially negatively affect sub-littoral habitats (Castège et al., 2014). Filter feeders are highly sensitive to oil pollution, particularly those inhabiting the tidal zones that experience high exposure and show correspondingly high mortality, as are bottom-dwelling organisms in areas where oil components are deposited by sedimentation (Zahn et al., 1981). There is little information on the effects of hydrocarbons on bryozoans. Ryland & Putron (1998) did not detect adverse effects of oil contamination on the bryozoan Alcyonidium spp. in Milford Haven or St. Catherine's Island, south Pembrokeshire, although it did alter the breeding period. Banks & Brown (2002) found that exposure to crude oil significantly impacted recruitment in the bryozoan Membranipora savartii. No evidence for Eunicella verrucosa was found, although White et al. (2012) reported on deep water gorgonian communities, including Swiftia pallida six months after the Deep Water Horizon oil spill. Stress in the gorgonians was observed including excessive mucus production, retracted polyps and smothering by brown flocculent material (floc). | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Synthetic compound contamination [Show more]Synthetic compound contaminationBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed but evidence is presented where available. Bryozoans are common members of the fouling community and amongst those organisms most resistant to antifouling measures, such as copper containing anti-fouling paints (Soule & Soule, 1979; Holt et al., 1995). Hoare & Hiscock (1974) suggested that Polyzoa (Bryozoa) were amongst the most intolerant species to acidified halogenated effluents in Amlwch Bay, Anglesey and reported that Flustra foliacea did not occur less than 165 m from the effluent source. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Radionuclide contamination [Show more]Radionuclide contaminationBenchmark. An increase in 10µGy/h above background levels. Further detail EvidenceNo evidence | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Introduction of other substances [Show more]Introduction of other substancesBenchmark. Exposure of marine species or habitat to one or more relevant contaminants via uncontrolled releases or incidental spills. Further detail EvidenceThis pressure is Not assessed. | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

De-oxygenation [Show more]De-oxygenationBenchmark. Exposure to dissolved oxygen concentration of less than or equal to 2 mg/l for one week (a change from WFD poor status to bad status). Further detail EvidenceIn general, respiration in most marine invertebrates does not appear to be significantly affected until extremely low concentrations are reached. For many benthic invertebrates this concentration is about 2 ml/l (ca 2.66 mg/l) (Herreid, 1980; Rosenberg et al., 1991; Diaz & Rosenberg, 1995). Cole et al. (1999) suggest possible adverse effects on marine species below 4 mg/l and probable adverse effects below 2 mg/l. Little information on the effects of oxygenation on bryozoans was found. Sagasti et al. (2000) reported that epifaunal communities, including the dominant bryozoans, were unaffected by periods of moderate hypoxia (ca 0.35 -1.4 ml/l) and short periods of anoxia (<0.35 ml/l) in the York River, Chesapeake Bay, although bryozoans were more abundant in the area with generally higher oxygen. However, estuarine species are likely to be better adapted to periodic changes in oxygenation. Bell (2002) reported that an oxycline at Lough Hyne (<5 % surface concentration) limited vertical colonization by Caryophillia smithii. No evidence was found concerning the effects of hypoxia for Eunicella verrucosa. However, as a species that lives in fully oxygenated waters in conditions of flowing waters, it is expected that it would be intolerant to decreased oxygen levels. Sensitivity assessment Despite limited evidence, Eunicella verrucosa, Axinella dissimils, and Caryophyllia smithii are unlikely to tolerate hypoxic events given their preference for moderate water movement and based on general information for marine invertebrates. Resistance is ‘Low’, resilience is 'Very Low’ and sensitivity is ‘High’. | LowHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Nutrient enrichment [Show more]Nutrient enrichmentBenchmark. Compliance with WFD criteria for good status. Further detail EvidenceWhilst little information on Pentapora spp. was found, O’Dea & Okamura (2000) found that annual growth of the bryozoan Flustra foliacea in western Europe has substantially increased since 1970. They suggest that this could be due to eutrophication in coastal regions due to organic pollution, leading to increased phytoplankton biomass (see Allen et al., 1998). Echavarri-Erasun et al. (2007) described the effects of deep water sewage discharge on the relative abundance of rocky reef communities. Species typical of hard substrata (including Caryophyllia smithii and bryozoans) increased in total richness and abundance near the outfall. Whilst Eunicella verrucosa could be at risk of competition from algae in shallow waters due to nutrient enrichment, CR.HCR.XFa.ByErSp.Eun is a circalittoral biotope and flora are not considered in this review. This biotope is considered to be 'Not sensitive' at the pressure benchmark, that assumes compliance with good status as defined by the WFD. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not sensitiveHelp |

Organic enrichment [Show more]Organic enrichmentBenchmark. A deposit of 100 gC/m2/yr. Further detail EvidenceCocito et al. (2013) demonstrated the ability of Eunicella verrucosa and other gorgonians to feed on both suspended organic matter and zooplankton. Whilst little information on Pentapora spp. was found, O’Dea & Okamura (2000) found that annual growth of the bryozoan Flustra foliacea in western Europe has substantially increased since 1970. They suggest that this could be due to eutrophication in coastal regions due to organic pollution, leading to increased phytoplankton biomass (see Allen et al., 1998). Novosel et al. (2004) described large colonies of Pentapora fascialis growing inside the plume of marine freshwater springs. The plumes had significantly higher concentrations of NO3-, SiO4, NH4+, NO2- and PO43-. Echavarri-Erasun et al. (2007) described the effects of deep water sewage discharge on the relative abundance of rocky reef communities. Species typical of hard substrata (including Caryophyllia smithii and bryozoans) increased in total richness and abundance near the outfall. No evidence was found for Axinella dissimilis. Sensitivity assessment. All characterizing species are sessile filter feeders and the evidence suggests that all tolerate, or increase in abundance when exposed to organic enrichment in the circalittoral. Resistance is ‘High’ resilience is ‘High’ and the biotope is ‘Not sensitive’. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Physical Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Physical loss (to land or freshwater habitat) [Show more]Physical loss (to land or freshwater habitat)Benchmark. A permanent loss of existing saline habitat within the site. Further detail EvidenceAll marine habitats and benthic species are considered to have a resistance of ‘None’ to this pressure and to be unable to recover from a permanent loss of habitat (resilience is ‘Very low’). Sensitivity within the direct spatial footprint of this pressure is, therefore ‘High’. Although no specific evidence is described, confidence in this assessment is ‘High’, due to the incontrovertible nature of this pressure. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Physical change (to another seabed type) [Show more]Physical change (to another seabed type)Benchmark. Permanent change from sedimentary or soft rock substrata to hard rock or artificial substrata or vice-versa. Further detail EvidenceIf rock were replaced with sediment, this would represent a fundamental change to the physical characteristics of the biotope and the species would be unlikely to recover. The biotope would be lost. Sensitivity assessment. Resistance to this pressure is considered ‘None’, and resilience ‘Very low’. Sensitivity has been assessed as ‘High’. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Physical change (to another sediment type) [Show more]Physical change (to another sediment type)Benchmark. Permanent change in one Folk class (based on UK SeaMap simplified classification). Further detail Evidence‘Not relevant’ to biotopes occurring on bedrock. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Habitat structure changes - removal of substratum (extraction) [Show more]Habitat structure changes - removal of substratum (extraction)Benchmark. The extraction of substratum to 30 cm (where substratum includes sediments and soft rock but excludes hard bedrock). Further detail EvidenceThe species characterizing this biotope are epifauna or epiflora occurring on rock and would be sensitive to the removal of the habitat. However, extraction of rock substratum is considered unlikely and this pressure is considered to be ‘Not relevant’ to hard substratum habitats. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Abrasion / disturbance of the surface of the substratum or seabed [Show more]Abrasion / disturbance of the surface of the substratum or seabedBenchmark. Damage to surface features (e.g. species and physical structures within the habitat). Further detail EvidencePhysical disturbance by fishing gear has been shown to adversely affect emergent epifaunal communities with hydroid and bryozoan matrices reported to be greatly reduced in fished areas (Jennings & Kaiser, 1998). Heavy mobile gears could also result in movement of boulders (Bullimore, 1985; Jennings & Kaiser, 1998) and sensitivity of Eunicella verrucosa to abrasion events has been assessed High in previous reviews (MacDonald, 1996; Hall et al., 2008; Tillin et al., 2010). Other studies suggest that Eunicella verrucosa may be more resistant to abrasion pressures. Eno et al. (2001) conducted experimental potting on areas containing fragile epifaunal species in Lyme Bay, south-west England. Divers observed that pink sea fan ‘flexed and bent before returning to an upright position under the weight of pots’. Although relatively resistant to a single event, long-term deterioration or the effects of repeated exposure were not clear (Eno et al., 2001). Observation of pots suggested that they were dragged along the bottom when wind and tidal streams were strong, however, little damage to epifauna was observed. Eunicella verrucosa were patchily distributed in areas subject to potting damage, but the study could not determine whether this was due to damage from potting (Eno et al., 2001). A further four year study on potting in the Lundy Marine Protected Area detected no significant differences in Eunicella verrucosa between areas subject to commercial potting and those where this activity was excluded. However Tinsley (2006) observed flattened sea fan that had continued growing, with new growth being aligned perpendicular to the current, so clearly even colonies of Eunicella verrucosa that are damaged can survive. Healthy Eunicella verrucosa are able to recover from minor damage and scratches to the coenenchyme (Tinsley, 2006), and the coenenchyme covering the axial skeleton will re-grow over scrapes on one side of the skeleton in about one week (Hiscock, pers. comm, cited in Hiscock, 2007.) While Hinz et al. (2011) reported that abundance and average body size of Eunicella verrucosa were not significantly affected by scallop dredging intensity, there is evidence of Eunicella verrucosa detached by mobile gear (Hiscock, pers. comm.) Some large Pentapora foliacea individuals were observed to be badly smashed by potting (Eno et al., 2001). Hiscock (2014) identified Axinella dissimilis as being very susceptible to towed fishing gear. Hinz et al. (2011) studied the effects of scallop dredging in Lyme Bay, UK and found that the presence of the erect sponge Axinella dissimilis was significantly higher at non-fished sites (33% occurrence) compared to fished sites (15% occurrence).Sensitivity assessment. Eunicella verrucosa is a sessile epifauna and is likely to be severely damaged by heavy gears, such as scallop dredging (MacDonald et al., 1996, Hiscock, pers. comm.). However, some studies suggest that the species may be more resistant, particularly to low intensity lighter abrasion pressures, such as pots and associated anchor damage (Eno et al. 1996). Axinella dissimilis is likely to be damaged by towed fishing gear (Hinz et al., 2011, Hiscock, 2014) Taking all the evidence into account, resistance is ‘Low’. Resilience is ‘Very Low’ and sensitivity as ‘High’. | LowHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Penetration or disturbance of the substratum subsurface [Show more]Penetration or disturbance of the substratum subsurfaceBenchmark. Damage to sub-surface features (e.g. species and physical structures within the habitat). Further detail EvidenceThe species characterizing this biotope group are epifauna or epiflora occurring on rock which is resistant to subsurface penetration. The assessment for abrasion at the surface only is therefore considered to equally represent sensitivity to this pressure. This pressure is thought ‘Not Relevant’ to hard rock biotopes. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Changes in suspended solids (water clarity) [Show more]Changes in suspended solids (water clarity)Benchmark. A change in one rank on the WFD (Water Framework Directive) scale e.g. from clear to intermediate for one year. Further detail EvidenceWhile high levels of suspended solids may inhibit feeding, colonies of the sea fan Eunicella verrucosa produce mucus to clear themselves of silt (Hiscock, 2007) and is probably tolerant of increases in suspended sediment (Hiscock et al., 2004b). Bunker (1986) reported that Eunicella verrucosa were mostly observed on bedrock or boulders, but occurred at sites described as ‘moderately silted’. Populations of Caryophyllia smithii were studied at three sites of differing sedimentation regimes in Lough Hyne, Ireland (Bell & Turner, 2000). The height, length, width and density of individuals were measured along with the depth of accumulated sediment on the rock substratum at each site. Calyx size was largest at the site of least sedimentation and smallest at the site of most sedimentation. In contrast, the height of individuals was greatest at the site of most sedimentation and smallest at the site of least sedimentation. The height of individuals correlated with the level of surrounding sediment. Caryophyllia smithii was more abundant in areas with higher sedimentation (Bell & Turner, 2000). Bryozoans are suspension feeders that may be adversely affected by increases in suspended sediment, due to clogging of their feeding apparatus. Axinella dissimilis is mainly found on upward facing clean or silty rock and whilst it tends to prefer clean oceanic water, it is tolerant of silt (Ackers et al., 1992). Sensitivity assessment CR.HCR.XFa.ByErSp.Eun occurs on bedrock in moderate water flow in the circalittoral and is unlikely to experience highly turbid conditions. From the evidence presented above, the characterizing species would probably tolerate some siltation and a change at the benchmark level is unlikely to cause mortality. Resistance is ‘High’, resilience is ‘High’ and the biotope is ‘Not sensitive’ at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Smothering and siltation rate changes (light) [Show more]Smothering and siltation rate changes (light)Benchmark. ‘Light’ deposition of up to 5 cm of fine material added to the seabed in a single discrete event. Further detail EvidenceWhile high levels of suspended sediment may inhibit feeding, colonies of the sea fan Eunicella verrucosa produce mucus to clear themselves of silt (Hiscock, 2007). It is however thought that smothering causes mortality (Hiscock et al., 2004b). Bunker (1986) reported that Eunicella verrucosa were mostly observed on bedrock or boulders but occurred at sites up to ‘moderately silted’. Eunicella verrucosa forms large colonies which branch profusely up to 30 cm in height (Picton & Morrow, 2005). Colonies of Pentapora fascialis can reach a height of 30 cm in the British Isles (Hayward & Ryland, 1979). Partial mortality due to siltation has been recorded in the Mediterranean (Cocito et al., 1998a) although recovery was observed in all but one colony (which fragmented into two smaller colonies). Caryophyllia smithii is small (approx. <3 cm height from the seabed) and would therefore likely be inundated in a “light” sedimentation event. However, Bell & Turner (2000) reported Caryophyllia smithii was abundant at sites of “moderate” sedimentation (7mm ± 0.5mm) in Lough Hyne. It is therefore likely that Caryophyllia smithii would be resistant to periodic sedimentation. If 5cm of sediment were removed rapidly, via tidal currents, Caryophyllia smithii would likely remain within the biotope. Lock et al. (2006) partly attributed fluctuations in Caryophyllia smithii abundance at Skomer Island to surface sediment cover. Ackers et al. (1992) described Axinella dissimilis as preferring clean oceanic water but tolerating silt. Hiscock & Jones (2004) reported that Axinella dissimilis (as Axinella polypoides) grew up to a height of ca 30 cm. Sensitivity assessment. Smothering by 5 cm would cover the majority of Caryophyllia smithii and the smallest examples of the other characterizing species and could result in limited mortality. Caryophyllia smithii has been reported as quite tolerant of temporary burial and the biotope occurs in moderate water flow and the sediment would likely be removed rapidly. Resistance was assessed as ‘High’, resilience as ‘High’ and sensitivity as ‘Not sensitive’ at the benchmark level. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Smothering and siltation rate changes (heavy) [Show more]Smothering and siltation rate changes (heavy)Benchmark. ‘Heavy’ deposition of up to 30 cm of fine material added to the seabed in a single discrete event. Further detail EvidenceWhile siltation may inhibit feeding, colonies of the sea fan Eunicella verrucosa produce mucus to clear themselves of silt (Hiscock, 2007). It is however thought that smothering causes mortality (Hiscock et al., 2004b). Bunker (1986) reported that Eunicella verrucosa were mostly observed on bedrock or boulders but occurred at sites up to ‘moderately silted’. Eunicella verrucosa forms large colonies which branch profusely up to 30 cm in height (Picton & Morrow, 2005). Colonies of Pentapora fascialis can reach a height of 30 cm in the British Isles (Hayward & Ryland, 1979). Partial mortality due to siltation has been recorded in the Mediterranean (Cocito et al., 1998a) although recovery was observed in all but one colony (which fragmented into two smaller colonies). Caryophyllia smithii is small (approx. <3 cm height from the seabed) and would therefore likely be inundated in a “heavy” sedimentation event. Whilst Bell & Turner (2000) reported Caryophyllia smithii was abundant at sites of “moderate” sedimentation (7mm ± 0.5mm) in Lough Hyne, it is unlikely that Caryophyllia smithii would survive. Burton et al. (2005) partly attributed fluctuations in Caryophyllia smithii abundance at Skomer Island to surface sediment cover. Ackers et al. (1992) described Axinella dissimilis as preferring clean oceanic water but tolerating silt. Hiscock & Jones (2004) reported that Axinella dissimilis (as Axinella polypoides) grew up to a height of ca 30 cm. Sensitivity assessment. Smothering by 30 cm of sediment would likely bury the majority of characterizing species, with only those individuals on boulders and vertical surfaces escaping burial. The biotope occurs in high energy environments and it is likely that the sediment would be removed. However, the damage to the resident community would depend on the time taken for the deposited sediment to be removed. Therefore, resistance was assessed as ‘Low’ as the worst-case scenario. Hence, resilience is probably ‘Very Low’ and sensitivity is assessed as ‘High’. | LowHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Litter [Show more]LitterBenchmark. The introduction of man-made objects able to cause physical harm (surface, water column, seafloor or strandline). Further detail EvidenceNot assessed. Ghost fishing by discarded fishing gear, lines and pots may cause some damage to the community, especially the tall erect epifauna, where discarded lines may catch the upright epifauna and increase drag, especially in stormy weather. Fishing lines can cause lesions to the gorgonian coenenchyme, leading to greater aggregates of epibionts which can eventually cause the branch to rupture (Bo et al., 2014). | Not Assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help | Not assessed (NA)Help |

Electromagnetic changes [Show more]Electromagnetic changesBenchmark. A local electric field of 1 V/m or a local magnetic field of 10 µT. Further detail EvidenceNo evidence | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Underwater noise changes [Show more]Underwater noise changesBenchmark. MSFD indicator levels (SEL or peak SPL) exceeded for 20% of days in a calendar year. Further detail EvidenceStanley et al. (2014) studied the effects of vessel noise on fouling communities and found that the bryozoans Bugula neritina, Watersipora arcuate and Watersipora subtorquata responded positively. More than twice as many bryozoans settled and established on surfaces with vessel noise (128 dB in the 30–10,000 Hz range) compared to those in silent conditions. Growth was also significantly higher in bryozoans exposed to noise, with 20% higher growth rate in encrusting and 35% higher growth rate in branching species. Sensitivity assessment. Whilst no evidence could be found on the effects of noise or vibrations on the characterizing species, it is unlikely that these species would be adversely affected by noise. Resistance to this pressure is assessed as 'High' and resilience as 'High'. This biotope is therefore considered to be 'Not sensitive'. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Introduction of light or shading [Show more]Introduction of light or shadingBenchmark. A change in incident light via anthropogenic means. Further detail EvidenceWhilst no evidence could be found for the effect of light on the characterizing species of these biotopes, it is unlikely that these species would be impacted. Resistance to this pressure is assessed as 'High' and resilience as 'High'. This biotope is therefore considered to be 'Not sensitive'. | HighHelp | HighHelp | Not sensitiveHelp |

Barrier to species movement [Show more]Barrier to species movementBenchmark. A permanent or temporary barrier to species movement over ≥50% of water body width or a 10% change in tidal excursion. Further detail EvidenceNot relevant: barriers and changes in tidal excursion are not relevant to biotopes restricted to open waters. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Death or injury by collision [Show more]Death or injury by collisionBenchmark. Injury or mortality from collisions of biota with both static or moving structures due to 0.1% of tidal volume on an average tide, passing through an artificial structure. Further detail EvidenceNot relevant to seabed habitats. NB. Collision by grounding vessels is addressed under ‘surface abrasion’. | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Visual disturbance [Show more]Visual disturbanceBenchmark. The daily duration of transient visual cues exceeds 10% of the period of site occupancy by the feature. Further detail EvidenceNot relevant | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help |

Biological Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Genetic modification & translocation of indigenous species [Show more]Genetic modification & translocation of indigenous speciesBenchmark. Translocation of indigenous species or the introduction of genetically modified or genetically different populations of indigenous species that may result in changes in the genetic structure of local populations, hybridization, or change in community structure. Further detail EvidenceNo evidence for the characterizing species could be found. | No evidence (NEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | No evidence (NEv)Help |

Introduction of microbial pathogens [Show more]Introduction of microbial pathogensBenchmark. The introduction of relevant microbial pathogens or metazoan disease vectors to an area where they are currently not present (e.g. Martelia refringens and Bonamia, Avian influenza virus, viral Haemorrhagic Septicaemia virus). Further detail EvidenceThe first recorded incidence of cold-water coral disease was noted in Eunicella verrucosa, in south-west England in 2002 (Hall-Spencer et al., 2007). Video surveys in south-west England from 2003 to 2006 of 634 separate colonies at 13 sites revealed that disease outbreaks were widespread and 9% of colonies had tissue necrosis. Coenenchyme became necrotic in diseased specimens, leading to tissue sloughing and exposing skeletal gorgonin to settlement by fouling organisms. Sites, where necrosis was found, had significantly higher incidences of fouling. No fungi were isolated from diseased or healthy tissue, but significantly higher concentrations of bacteria occurred in diseased specimens. Vibrio isolated from Eunicella verrucosa did not induce disease at 15°C, but, at 20°C, controls remained healthy and test gorgonians became diseased, regardless of whether Vibrio was isolated from diseased or healthy colonies. Bacteria associated with diseased tissue produced proteolytic and cytolytic enzymes that damaged Eunicella verrucosa tissue and may be responsible for the necrosis observed. Monitoring at the site where the disease was first noted showed new gorgonian recruitment from 2003 to 2006; 5 of the 18 necrotic colonies videoed in 2003 had died and become completely overgrown, whereas others had continued to grow around a dead central area (Hall-Spencer et al., 2007). No evidence of disease in the characterizing bryozoan could be found. Gochfeld et al. (2012) found that diseased sponges hosted significantly different bacterial assemblages compared to healthy sponges, with diseased sponges also exhibiting a significant decline in sponge mass and protein content. Sponge disease epidemics can have serious long-term effects on sponge populations, especially in long-lived, slow-growing species (Webster, 2007). Numerous sponge populations have been brought to the brink of extinction including cases in the Caribbean with 70-95% disappearance of sponge specimens (Galstoff, 1942), the Mediterranean (Vacelet, 1994; Gaino et al.,1992). Decaying patches and white bacterial film were reported in Haliclona oculata and Halichondria panicea in North Wales, 1988-89 (Webster, 2007). Specimens of Cliona spp. have exhibited blackened damage since 2013 in Skomer. Preliminary results have shown that clean, fouled and blackened Cliona all have very different bacterial communities. Blackened Cliona are effectively dead and have a bacterial community similar to marine sediments. The fouled Cliona have a very distinct bacterial community which may suggest a specific pathogen caused the effect (Burton, pers comm; Preston & Burton, 2015). Sensitivity assessment. Sponge diseases have caused limited mortality in some species in the British Isles (although no evidence was found for axinellid sponges), mass mortality and even extinction have been reported further afield. Based on this evidence, together with mortality linked to disease in Eunicella verrucosa, resistance is assessed as ‘Medium’, resilience as ‘Very Low’ sensitivity as ‘Medium’. Confidence is 'Low'. | MediumHelp | Very LowHelp | MediumHelp |

Removal of target species [Show more]Removal of target speciesBenchmark. Removal of species targeted by fishery, shellfishery or harvesting at a commercial or recreational scale. Further detail EvidenceEunicella verrucosa has historically been harvested as a curio by divers and was collected until recently in the British Isles (Bunker, 1986; Wells et al., 1983 cited in Koomen & Helsdingen, 1996), however, it is now protected under schedule 5 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and harvesting is illegal. No evidence of harvesting of the other characterizing species was found. Hiscock (2003) stated that the greatest loss of Axinella dissimilis at Lundy might have been due to collecting during scientific studies in the 1970s. No indication of recovery was evident. Axinella damicornis was harvested in Lough Hyne during the 1980s (for molecular investigations) and the populations were reduced to very low densities, which subsequently recovered very slowly, although they are now considered to be back to their original densities (Bell, 2007). Sensitivity assessment. The characterizing Eunicella verrucosa and the sponge Axinella dissimilis are sessile, epifaunal and would have no resistance to harvesting. Resistance has been assessed as ‘None’, resilience as ‘Very Low’ and sensitivity is, therefore ‘High’. | NoneHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Removal of non-target species [Show more]Removal of non-target speciesBenchmark. Removal of features or incidental non-targeted catch (by-catch) through targeted fishery, shellfishery or harvesting at a commercial or recreational scale. Further detail EvidenceRemoval of the characteristic epifauna due to by-catch is likely to remove a proportion of the biotope and change the biological character of the biotope. For example, Eunicella verrucosa and, in particular, Axinella dissimilis, are sessile epifauna and are likely to be severely damaged by heavy gears, such as scallop dredging (MacDonald et al., 1996; Hinz et al., 2011). This biotope may be removed or damaged by static or mobile gears that are targeting other species. These direct, physical impacts are assessed through the abrasion and penetration of the seabed pressures. The sensitivity assessment for this pressure considers any biological/ecological effects resulting from the removal of non-target species in this biotope. The unintentional removal of the important characterizing species will result in loss of the biotope. Therefore, Sensitivity assessment. Therefore, resistance is ‘Low’, resilience is ‘Very Low’ and sensitivity is ‘High’ | LowHelp | Very LowHelp | HighHelp |

Introduction or spread of invasive non-indigenous species (INIS) Pressures

Use [show more] / [show less] to open/close text displayed

| Resistance | Resilience | Sensitivity | |

Other INIS [Show more]Other INISEvidenceThis biotope is classified as circalittoral and therefore no algal species have been considered. Crepidula fornicata larvae require hard substrata for settlement. It prefers muddy gravelly, shell-rich, substrata that include gravel, or shells of other Crepidula, or other species e.g., oysters, and mussels. It is highly gregarious and seeks out adult shells for settlement, forming characteristic ‘stacks’ of adults. But it also recorded from rock, artificial substrata, and Sabellaria alveolata reefs (Blanchard, 1997, 2009; Bohn et al., 2012, 2013a, 2013b, 2015; De Montaudouin et al., 2018; Hinz et al., 2011; Helmer et al., 2019; Powell-Jennings & Calloway, 2018; Preston et al., 2020; Tillin et al., 2020). Close examination of the literature (2023) shows that evidence of its colonization and density on bedrock in the infralittoral or circalittoral was lacking. Tillin et al. (2020) suggested that Crepidula could colonize circalittoral rock due to its presence on tide-swept rough grounds in the English Channel (Hinz et al., 2011). However, Hinz et al. (2011) reported that Crepidula fornicata only dominated one assemblage (with an average of 181 individuals per trawl) on gravel substratum with boulders. Bohn et al. (2015) noted that Crepidula occurred at low density or was absent in areas dominated by boulders, and Bohn et al. (2013a, 2013b, 2015) and Preston et al. (2020) showed that while Crepidula could settle on slate panels or ‘stone’ it preferred shell, especially that of conspecifics. In addition, no evidence was found of the effect of Crepidula populations on faunal turf-dominated habitats. It was only recorded at low density (0.1-0.9/m2) in one faunal turf biotope (CR.MCR.CFaVS.CuSpH.As) (JNCC, 2015). Faunal turfs are dominated by suspension feeders so larval predation is probably high, which may prevent colonization by Crepidula. Also, faunal turf species actively compete for space and many are fast growing and opportunistic, so may out-compete Crepidula for space even if it gained a foothold in the community. Several invasive bryozoans are of concern including Schizoporella japonica (Ryland et al., 2014) and Tricellaria inopinata (Dyrynda et al., 2000; Cook et al., 2013b), although 'No evidence' of these affecting CR.HCR.XFa.ByErSp.Eun was found. Sensitivity assessment. The circalittoral rock characterizing this biotope is likely to be unsuitable for the colonization by Crepidula fornicata due to the extremely wave exposed to moderately wave exposed conditions, in which wave action and storms may mitigate or prevent the colonization by Crepidula at high densities, although Crepidula has been recorded from areas of strong tidal streams (Hinz et al., 2011). In addition, no evidence was found of the effect of Crepidula populations on faunal turf-dominated habitats or infralittoral or circalittoral rock habitats. At present, there is 'Insufficient evidence' to suggest that the circalittoral rock biotopes are sensitive to colonization by Crepidula fornicata or other invasive species; further evidence is required. | Insufficient evidence (IEv)Help | Not relevant (NR)Help | Help |

Bibliography

Ackers, R.G.A., Moss, D. & Picton, B.E. 1992. Sponges of the British Isles (Sponges: V): a colour guide and working document. Ross-on-Wye: Marine Conservation Society.

Allen, J., Slinn, D., Shummon, T., Hurtnoll, R. & Hawkins, S., 1998. Evidence for eutrophication of the Irish Sea over four decades. Limnology and Oceanography, 43 (8), 1970-1974.

Anonymous, 1999l. Pink sea-fan (Eunicella verrucosa). Species Action Plan. In UK Biodiversity Group. Tranche 2 Action Plans. English Nature for the UK Biodiversity Group, Peterborough., English Nature for the UK Biodiversity Group, Peterborough.

Banks, P.D. & Brown, K.M., 2002. Hydrocarbon effects on fouling assemblages: the importance of taxonomic differences, seasonal, and tidal variation. Marine Environmental Research, 53 (3), 311-326.

Bell, J.J., 2007. The ecology of sponges in Lough Hyne Marine Nature Reserve (south-west Ireland): past, present and future perspectives. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 87 (6), 1655-1668.

Bell, J.J. & Turner, J.R., 2000. Factors influencing the density and morphometrics of the cup coral Caryophyllia smithii in Lough Hyne. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 80, 437-441. DOI https://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0025315400002137

Bell, J.J., 2002. Morphological responses of a cup coral to environmental gradients. Sarsia, 87, 319-330. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/00364820260400825

Blanchard, M., 2009. Recent expansion of the slipper limpet population (Crepidula fornicata) in the Bay of Mont-Saint-Michel (Western Channel, France). Aquatic Living Resources, 22 (1), 11-19. DOI https://doi.org/10.1051/alr/2009004

Blanchard, M., 1997. Spread of the slipper limpet Crepidula fornicata (L.1758) in Europe. Current state and consequences. Scientia Marina, 61, Supplement 9, 109-118. Available from: http://scimar.icm.csic.es/scimar/index.php/secId/6/IdArt/290/

Bo, M., Bava, S., Canese, S., Angiolillo, M., Cattaneo-Vietti, R. & Bavestrello, G., 2014. Fishing impact on deep Mediterranean rocky habitats as revealed by ROV investigation. Biological Conservation, 171, 167-176. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2014.01.011

Bohn, K., Richardson, C. & Jenkins, S., 2012. The invasive gastropod Crepidula fornicata: reproduction and recruitment in the intertidal at its northernmost range in Wales, UK, and implications for its secondary spread. Marine Biology, 159 (9), 2091-2103. DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-012-1997-3

Bohn, K., Richardson, C.A. & Jenkins, S.R., 2015. The distribution of the invasive non-native gastropod Crepidula fornicata in the Milford Haven Waterway, its northernmost population along the west coast of Britain. Helgoland Marine Research, 69 (4), 313.

Bohn, K., Richardson, C.A. & Jenkins, S.R., 2013a. Larval microhabitat associations of the non-native gastropod Crepidula fornicata and effects on recruitment success in the intertidal zone. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 448, 289-297. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2013.07.020

Bohn, K., Richardson, C.A. & Jenkins, S.R., 2013b. The importance of larval supply, larval habitat selection and post-settlement mortality in determining intertidal adult abundance of the invasive gastropod Crepidula fornicata. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 440, 132-140. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jembe.2012.12.008

Budd, G.C. 2008. Alcyonium digitatum Dead man's fingers. In Tyler-Walters H. and Hiscock K. (eds) Marine Life Information Network: Biology and Sensitivity Key Information Reviews, [on-line]. Plymouth: Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. Available from: http://www.marlin.ac.uk/species/detail/1187

Bullimore, B., 1985. An investigation into the effects of scallop dredging within the Skomer Marine Reserve. Report to the Nature Conservancy Council by the Skomer Marine Reserve Subtidal Monitoring Project, S.M.R.S.M.P. Report, no 3., Nature Conservancy Council.

Bunker, F., 1986. Survey of the Broad sea fan Eunicella verrucosa around Skomer Marine Reserve in 1985 and a review of its importance (together with notes on some other species of interest and data concerning previously unsurveyed or poorly documented areas). Volume I. Report to the NCC by the Field Studies Council.

Castège, I., Milon, E. & Pautrizel, F., 2014. Response of benthic macrofauna to an oil pollution: Lessons from the “Prestige” oil spill on the rocky shore of Guéthary (south of the Bay of Biscay, France). Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography, 106, 192-197.

Cerrano, C., Bavestrello, G., Bianchi, C., Cattaneo-Vietti, R., Bava, S., Morganti, C., Morri, C., Picco, P., Sara, G., Schiaparelli, S., Siccardi, A. & Sponga, F., 2000. A catastrophic mass-mortality episode of gorgonians and other organisms in the Ligurian Sea (North-western Mediterranean), summer 1999. Ecology Letters, 3 (4), 284-293. DOI https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2000.00152.x

Chan, I., Tseng, L. C., Kâ, S., Chang, C. F. & Hwang, J. S., 2012. An experimental study of the response of the gorgonian coral Subergorgia suberosa to polluted seawater from a former coastal mining site in Taiwan. Zoological Studies, 51 (1), 27-37.

Chesher, R.H., 1975. Biological Impact of a Large-Scale Desalination Plant at Key West, Florida. Elsevier Oceanography Series, 12, 99-153.

Cocito, S. & Sgorbini, S., 2014. Long-term trend in substratum occupation by a clonal, carbonate bryozoan in a temperate rocky reef in times of thermal anomalies. Marine Biology, 161 (1), 17-27.

Cocito, S., Ferdeghini, F., & Sgorbini, S., 1998b. Pentapora fascialis (Pallas) [Cheilostomata: Ascophora] colonization of one sublittoral rocky site after sea-storm in the northwest Mediterranean. Hydrobiologia, 375/376, 59-66.

Cocito, S., Ferrier-Pagès, C., Cupido, R., Rottier, C., Meier-Augenstein, W., Kemp, H., Reynaud, S. & Peirano, A., 2013. Nutrient acquisition in four Mediterranean gorgonian species. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 473, 179-188.

Cocito, S., Sgarbini, S. & Bianchi, C.N., 1998a. Aspects of the biology of the bryozoan Pentapora fascialis in the northwestern Mediterranean. Marine Biology, 131, 73-82.

Cole, S., Codling, I.D., Parr, W. & Zabel, T., 1999. Guidelines for managing water quality impacts within UK European Marine sites. Natura 2000 report prepared for the UK Marine SACs Project. 441 pp., Swindon: Water Research Council on behalf of EN, SNH, CCW, JNCC, SAMS and EHS. [UK Marine SACs Project.]. Available from: http://ukmpa.marinebiodiversity.org/uk_sacs/pdfs/water_quality.pdf

Coma, R., Linares, C., Ribes, M., Diaz, D., Garrabou, J. & Ballesteros, E., 2006. Consequences of a mass mortality in populations of Eunicella singularis (Cnidaria: Octorallia) in Menorca (NW Mediterranean). Marine Ecology Progress Series, 331, 51-60.

Coma, R., Ribes, M., Zabela, M. & Gili, J.-M. 1995. Reproduction and cycle of gonadial development in the Mediterranean gorgonian Paramuricea clavata. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 117, 173-183.

Connor, D.W., Allen, J.H., Golding, N., Howell, K.L., Lieberknecht, L.M., Northen, K.O. & Reker, J.B., 2004. The Marine Habitat Classification for Britain and Ireland. Version 04.05. ISBN 1 861 07561 8. In JNCC (2015), The Marine Habitat Classification for Britain and Ireland Version 15.03. [2019-07-24]. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough. Available from https://mhc.jncc.gov.uk/

Connor, D.W., Dalkin, M.J., Hill, T.O., Holt, R.H.F. & Sanderson, W.G., 1997a. Marine biotope classification for Britain and Ireland. Vol. 2. Sublittoral biotopes. Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough, JNCC Report no. 230, Version 97.06., Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Peterborough, JNCC Report no. 230, Version 97.06.

Cook, E.J., Stehlíková, J., Beveridge, C.M., Burrows, M.T., De Blauwe, H. & Faasse, M., 2013b. Distribution of the invasive bryozoan Tricellaria inopinata in Scotland and a review of its European expansion. Aquatic Invasions, 8 (3), 281-288.

De Kluijver, M.J., 1993. Sublittoral hard-substratum communities off Orkney and St Abbs (Scotland). Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 73 (4), 733-754.

De Montaudouin, X., Blanchet, H. & Hippert, B., 2018. Relationship between the invasive slipper limpet Crepidula fornicata and benthic megafauna structure and diversity, in Arcachon Bay. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, 98 (8), 2017-2028. DOI https://doi.org/10.1017/s0025315417001655

Diaz, R.J. & Rosenberg, R., 1995. Marine benthic hypoxia: a review of its ecological effects and the behavioural responses of benthic macrofauna. Oceanography and Marine Biology: an Annual Review, 33, 245-303.

Dyrynda, P., Fairall, V., Occhipinti Ambrogi, A. & d'Hondt, J.-L., 2000. The distribution, origins and taxonomy of Tricellaria inopinata d'Hondt and Occhipinti Ambrogi, 1985, an invasive bryozoan new to the Atlantic. Journal of Natural History, 34 (10), 1993-2006.

Dyrynda, P.E.J., 1994. Hydrodynamic gradients and bryozoan distributions within an estuarine basin (Poole Harbour, UK). In Proceedings of the 9th International Bryozoology conference, Swansea, 1992. Biology and Palaeobiology of Bryozoans (ed. P.J. Hayward, J.S. Ryland & P.D. Taylor), pp.57-63. Fredensborg: Olsen & Olsen.

Echavarri-Erasun, B., Juanes, J.A., García-Castrillo, G. & Revilla, J.A., 2007. Medium-term responses of rocky bottoms to sewage discharges from a deepwater outfall in the NE Atlantic. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 54 (7), 941-954.

Eggleston, D., 1972b. Factors influencing the distribution of sub-littoral ectoprocts off the south of the Isle of Man (Irish Sea). Journal of Natural History, 6, 247-260.

Eno, N.C., MacDonald, D. & Amos, S.C., 1996. A study on the effects of fish (Crustacea/Molluscs) traps on benthic habitats and species. Final report to the European Commission. Study Contract, no. 94/076.

Eno, N.C., MacDonald, D.S., Kinnear, J.A.M., Amos, C.S., Chapman, C.J., Clark, R.A., Bunker, F.S.P.D. & Munro, C., 2001. Effects of crustacean traps on benthic fauna ICES Journal of Marine Science, 58, 11-20. DOI https://doi.org/10.1006/jmsc.2000.0984

Fish, J.D. & Fish, S., 1996. A student's guide to the seashore. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fowler, S. & Laffoley, D., 1993. Stability in Mediterranean-Atlantic sessile epifaunal communities at the northern limits of their range. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 172 (1), 109-127. DOI https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-0981(93)90092-3

Gaino, E., Pronzato, R., Corriero, G. & Buffa, P., 1992. Mortality of commercial sponges: incidence in two Mediterranean areas. Italian Journal of Zoology, 59 (1), 79-85.